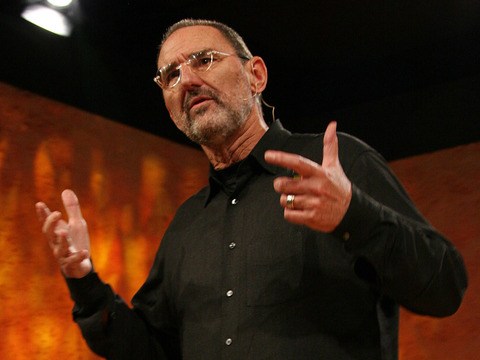

Good morning. When I was a little boy, I had an experience that changed my life, and is in fact why I'm here today. That one moment profoundly affected how I think about art, design and engineering.

As background, I was fortunate enough to grow up in a family of loving and talented artists in one of the world's great cities. My dad, John Ferren, who died when I was 15, was an artist by both passion and profession, as is my mom, Rae. He was one of the New York School abstract expressionists who, together with his contemporaries, invented American modern art, and contributed to moving the American zeitgeist towards modernism in the 20th century. Isn't it remarkable that, after thousands of years of people doing mostly representational art, that modern art, comparatively speaking, is about 15 minutes old, yet now pervasive. As with many other important innovations, those radical ideas required no new technology, just fresh thinking and a willingness to experiment, plus resiliency in the face of near-universal criticism and rejection. In our home, art was everywhere. It was like oxygen, around us and necessary for life. As I watched him paint, Dad taught me that art was not about being decorative, but was a different way of communicating ideas, and in fact one that could bridge the worlds of knowledge and insight.

Given this rich artistic environment, you'd assume that I would have been compelled to go into the family business, but no. I followed the path of most kids who are genetically programmed to make their parents crazy. I had no interest in becoming an artist, certainly not a painter. What I did love was electronics and machines -- taking them apart, building new ones, and making them work. Fortunately, my family also had engineers in it, and with my parents, these were my first role models. What they all had in common was they worked very, very hard. My grandpa owned and operated a sheet metal kitchen cabinet factory in Brooklyn. On weekends, we would go together to Cortlandt Street, which was New York City's radio row. There we would explore massive piles of surplus electronics, and for a few bucks bring home treasures like Norden bombsights and parts from the first IBM tube-based computers. I found these objects both useful and fascinating. I learned about engineering and how things worked, not at school but by taking apart and studying these fabulously complex devices. I did this for hours every day, apparently avoiding electrocution. Life was good.

However, every summer, sadly, the machines got left behind while my parents and I traveled overseas to experience history, art and design. We visited the great museums and historic buildings of both Europe and the Middle East, but to encourage my growing interest in science and technology, they would simply drop me off in places like the London Science Museum, where I would wander endlessly for hours by myself studying the history of science and technology.

Then, when I was about nine years old, we went to Rome. On one particularly hot summer day, we visited a drum-shaped building that from the outside was not particularly interesting. My dad said it was called the Pantheon, a temple for all of the gods. It didn't look all that special from the outside, as I said, but when we walked inside, I was immediately struck by three things: First of all, it was pleasantly cool despite the oppressive heat outside. It was very dark, the only source of light being an big open hole in the roof. Dad explained that this wasn't a big open hole, but it was called the oculus, an eye to the heavens. And there was something about this place, I didn't know why, that just felt special. As we walked to the center of the room, I looked up at the heavens through the oculus. This was the first church that I'd been to that provided an unrestricted view between God and man. But I wondered, what about when it rained? Dad may have called this an oculus, but it was, in fact, a big hole in the roof. I looked down and saw floor drains had been cut into the stone floor. As I became more accustomed to the dark, I was able to make out details of the floor and the surrounding walls. No big deal here, just the same statuary stuff that we'd seen all over Rome. In fact, it looked like the Appian Way marble salesman showed up with his sample book, showed it to Hadrian, and Hadrian said, "We'll take all of it." (Laughter)

But the ceiling was amazing. It looked like a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome. I'd seen these before, and Bucky was friends with my dad. It was modern, high-tech, impressive, a huge 142-foot clear span which, not coincidentally, was exactly its height. I loved this place. It was really beautiful and unlike anything I'd ever seen before, so I asked my dad, "When was this built?" He said, "About 2,000 years ago." And I said, "No, I mean, the roof." You see, I assumed that this was a modern roof that had been put on because the original was destroyed in some long-past war. He said, "It's the original roof."

That moment changed my life, and I can remember it as if it were yesterday. For the first time, I realized people were smart 2,000 years ago. (Laughter) This had never crossed my mind. I mean, to me, the pyramids at Giza, we visited those the year before, and sure they're impressive, nice enough design, but look, give me an unlimited budget, 20,000 to 40,000 laborers, and about 10 to 20 years to cut and drag stone blocks across the countryside, and I'll build you pyramids too. But no amount of brute force gets you the dome of the Pantheon, not 2,000 years ago, nor today. And incidentally, it is still the largest unreinforced concrete dome that's ever been built. To build the Pantheon took some miracles. By miracles, I mean things that are technically barely possible, very high-risk, and might not be actually accomplishable at this moment in time, certainly not by you.

For example, here are some of the Pantheon's miracles. To make it even structurally possible, they had to invent super-strong concrete, and to control weight, varied the density of the aggregate as they worked their way up the dome. For strength and lightness, the dome structure used five rings of coffers, each of diminishing size, which imparts a dramatic forced perspective to the design. It was wonderfully cool inside because of its huge thermal mass, natural convection of air rising up through the oculus, and a Venturi effect when wind blows across the top of the building. I discovered for the first time that light itself has substance. The shaft of light beaming through the oculus was both beautiful and palpable, and I realized for the first time that light could be designed. Further, that of all of the forms of design, visual design, they were all kind of irrelevant without it, because without light, you can't see any of them. I also realized that I wasn't the first person to think that this place was really special. It survived gravity, barbarians, looters, developers and the ravages of time to become what I believe is the longest continuously occupied building in history.

Largely because of that visit, I came to understand that, contrary to what I was being told in school, the worlds of art and design were not, in fact, incompatible with science and engineering. I realized, when combined, you could create things that were amazing that couldn't be done in either domain alone. But in school, with few exceptions, they were treated as separate worlds, and they still are. My teachers told me that I had to get serious and focus on one or the other. However, urging me to specialize only caused me to really appreciate those polymaths like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin, people who did exactly the opposite. And this led me to embrace and want to be in both worlds.

So then how do these projects of unprecedented creative vision and technical complexity like the Pantheon actually happen? Someone themselves, perhaps Hadrian, needed a brilliant creative vision. They also needed the storytelling and leadership skills necessary to fund and execute it, and a mastery of science and technology with the ability and knowhow to push existing innovations even farther. It is my belief that to create these rare game changers requires you to pull off at least five miracles. The problem is, no matter how talented, rich or smart you are, you only get one to one and a half miracles. That's it. That's the quota. Then you run out of time, money, enthusiasm, whatever. Remember, most people can't even imagine one of these technical miracles, and you need at least five to make a Pantheon. In my experience, these rare visionaries who can think across the worlds of art, design and engineering have the ability to notice when others have provided enough of the miracles to bring the goal within reach. Driven by the clarity of their vision, they summon the courage and determination to deliver the remaining miracles and they often take what other people think to be insurmountable obstacles and turn them into features. Take the oculus of the Pantheon. By insisting that it be in the design, it meant you couldn't use much of the structural technology that had been developed for Roman arches. However, by instead embracing it and rethinking weight and stress distribution, they came up with a design that only works if there's a big hole in the roof. That done, you now get the aesthetic and design benefits of light, cooling and that critical direct connection with the heavens. Not bad. These people not only believed that the impossible can be done, but that it must be done.

Enough ancient history. What are some recent examples of innovations that combine creative design and technological advances in a way so profound that they will be remembered a thousand years from now? Well, putting a man on the moon was a good one, and returning him safely to Earth wasn't bad either. Talk about one giant leap: It's hard to imagine a more profound moment in human history than when we first left our world to set foot on another.

So what came after the moon? One is tempted to say that today's pantheon is the Internet, but I actually think that's quite wrong, or at least it's only part of the story. The Internet isn't a Pantheon. It's more like the invention of concrete: important, absolutely necessary to build the Pantheon, and enduring, but entirely insufficient by itself. However, just as the technology of concrete was critical in realization of the Pantheon, new designers will use the technologies of the Internet to create novel concepts that will endure. The smartphone is a perfect example. Soon the majority of people on the planet will have one, and the idea of connecting everyone to both knowledge and each other will endure.

So what's next? What imminent advance will be the equivalent of the Pantheon? Thinking about this, I rejected many very plausible and dramatic breakthroughs to come, such as curing cancer. Why? Because Pantheons are anchored in designed physical objects, ones that inspire by simply seeing and experiencing them, and will continue to do so indefinitely. It is a different kind of language, like art. These other vital contributions that extend life and relieve suffering are, of course, critical, and fantastic, but they're part of the continuum of our overall knowledge and technology, like the Internet.

So what is next? Perhaps counterintuitively, I'm guessing it's a visionary idea from the late 1930s that's been revived every decade since: autonomous vehicles. Now you're thinking, give me a break. How can a fancy version of cruise control be profound? Look, much of our world has been designed around roads and transportation. These were as essential to the success of the Roman Empire as the interstate highway system to the prosperity and development of the United States. Today, these roads that interconnect our world are dominated by cars and trucks that have remained largely unchanged for 100 years. Although perhaps not obvious today, autonomous vehicles will be the key technology that enables us to redesign our cities and, by extension, civilization. Here's why: Once they become ubiquitous, each year, these vehicles will save tens of thousands of lives in the United States alone and a million globally. Automotive energy consumption and air pollution will be cut dramatically. Much of the road congestion in and out of our cities will disappear. They will enable compelling new concepts in how we design cities, work, and the way we live. We will get where we're going faster and society will recapture vast amounts of lost productivity now spent sitting in traffic basically polluting.

But why now? Why do we think this is ready? Because over the last 30 years, people from outside the automotive industry have spent countless billions creating the needed miracles, but for entirely different purposes. It took folks like DARPA, universities, and companies completely outside of the automotive industry to notice that if you were clever about it, autonomy could be done now. So what are the five miracles needed for autonomous vehicles? One, you need to know where you are and exactly what time it is. This was solved neatly by the GPS system, Global Positioning System, that the U.S. Government put in place. You need to know where all the roads are, what the rules are, and where you're going. The various needs of personal navigation systems, in-car navigation systems, and web-based maps address this. You must have near-continuous communication with high-performance computing networks and with others nearby to understand their intent. The wireless technologies developed for mobile devices, with some minor modifications, are completely suitable to solve this. You'll probably want some restricted roadways to get started that both society and its lawyers agree are safe to use for this. This will start with the HOV lanes and move from there. But finally, you need to recognize people, signs and objects. Machine vision, special sensors, and high-performance computing can do a lot of this, but it turns out a lot is not good enough when your family is on board. Occasionally, humans will need to do sense-making. For this, you might actually have to wake up your passenger and ask them what the hell that big lump is in the middle of the road. Not so bad, and it will give us a sense of purpose in this new world. Besides, once the first drivers explain to their confused car that the giant chicken at the fork in the road is actually a restaurant, and it's okay to keep driving, every other car on the surface of the Earth will know that from that point on.

Five miracles, mostly delivered, and now you just need a clear vision of a better world filled with autonomous vehicles with seductively beautiful and new functional designs plus a lot of money and hard work to bring it home. The beginning is now only a handful of years away, and I predict that autonomous vehicles will permanently change our world over the next several decades.

In conclusion, I've come to believe that the ingredients for the next Pantheons are all around us, just waiting for visionary people with the broad knowledge, multidisciplinary skills, and intense passion to harness them to make their dreams a reality. But these people don't spontaneously pop into existence. They need to be nurtured and encouraged from when they're little kids. We need to love them and help them discover their passions. We need to encourage them to work hard and help them understand that failure is a necessary ingredient for success, as is perseverance. We need to help them to find their own role models, and give them the confidence to believe in themselves and to believe that anything is possible, and just as my grandpa did when he took me shopping for surplus, and just as my parents did when they took me to science museums, we need to encourage them to find their own path, even if it's very different from our own.

But a cautionary note: We also need to periodically pry them away from their modern miracles, the computers, phones, tablets, game machines and TVs, take them out into the sunlight so they can experience both the natural and design wonders of our world, our planet and our civilization. If we don't, they won't understand what these precious things are that someday they will be resopnsible for protecting and improving. We also need them to understand something that doesn't seem adequately appreciated in our increasingly tech-dependent world, that art and design are not luxuries, nor somehow incompatible with science and engineering. They are in fact essential to what makes us special.

Someday, if you get the chance, perhaps you can take your kids to the actual Pantheon, as we will our daughter Kira, to experience firsthand the power of that astonishing design, which on one otherwise unremarkable day in Rome, reached 2,000 years into the future to set the course for my life.

Thank you.

(Applause)