Frank Gehry: I listened to this scientist this morning. Dr. Mullis was talking about his experiments, and I realized that I almost became a scientist. When I was 14 my parents bought me a chemistry set and I decided to make water. (Laughter) So, I made a hydrogen generator and I made an oxygen generator, and I had the two pipes leading into a beaker and I threw a match in. (Laughter) And the glass -- luckily I turned around -- I had it all in my back and I was about 15 feet away. The wall was covered with ... I had an explosion.

Richard Saul Wurman: Really?

FG: People on the street came and knocked on the door to see if I was okay. RSW: ... huh. (Laughter)

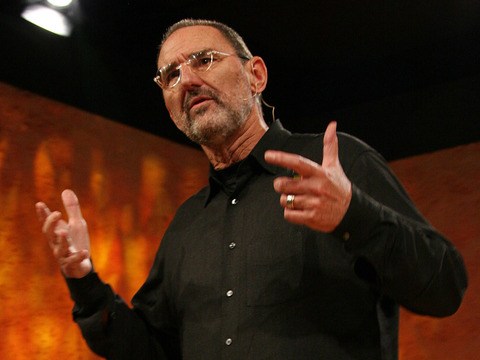

I'd like to start this session again. The gentleman to my left is the very famous, perhaps overly famous, Frank Gehry. (Laughter) (Applause) And Frank, you've come to a place in your life, which is astonishing. I mean it is astonishing for an artist, for an architect, to become actually an icon and a legend in their own time. I mean you have become, whether you can giggle at it because it's a funny ... you know, it's a strange thought, but your building is an icon -- you can draw a little picture of that building, it can be used in ads -- and you've had not rock star status, but celebrity status in doing what you wanted to do for most of your life. And I know the road was extremely difficult. And it didn't seem, at least, that your sell outs, whatever they were, were very big. You kept moving ahead in a life where you're dependent on working for somebody. But that's an interesting thing for a creative person. A lot of us work for people; we're in the hands of other people. And that's one of the great dilemmas -- we're in a creativity session -- it's one of the great dilemmas in creativity: how to do work that's big enough and not sell out. And you've achieved that and that makes your win doubly big, triply big. It's not quite a question but you can comment on it. It's a big issue.

FG: Well, I've always just ... I've never really gone out looking for work. I always waited for it to sort of hit me on the head. And when I started out, I thought that architecture was a service business and that you had to please the clients and stuff. And I realized when I'd come into the meetings with these corrugated metal and chain link stuff, and people would just look at me like I'd just landed from Mars. But I couldn't do anything else. That was my response to the people in the time. And actually, it was responding to clients that I had who didn't have very much money, so they couldn't afford very much. I think it was circumstantial.

Until I got to my house, where the client was my wife. We bought this tiny little bungalow in Santa Monica and for like 50 grand I built a house around it. And a few people got excited about it. I was visiting with an artist, Michael Heizer, out in the desert near Las Vegas somewhere. He's building this huge concrete place. And it was late in the evening. We'd had a lot to drink. We were standing out in the desert all alone and, thinking about my house, he said, "Did it ever occur to you if you built stuff more permanent, somewhere in 2000 years somebody's going to like it?" (Laughter) So, I thought, "Yeah, that's probably a good idea." Luckily I started to get some clients that had a little more money, so the stuff was a little more permanent. But I just found out the world ain't going to last that long, this guy was telling us the other day. So where do we go now? Back to -- everything's so temporary.

I don't see it the way you characterized it. For me, every day is a new thing. I approach each project with a new insecurity, almost like the first project I ever did, and I get the sweats, I go in and start working, I'm not sure where I'm going -- if I knew where I was going, I wouldn't do it. When I can predict or plan it, I don't do it. I discard it. So I approach it with the same trepidation. Obviously, over time I have a lot more confidence that it's going to be OK. I do run a kind of a business -- I've got 120 people and you've got to pay them, so there's a lot of responsibility involved -- but the actual work on the project is with, I think, a healthy insecurity.

And like the playwright said the other day -- I could relate to him: you're not sure. When Bilbao was finished and I looked at it, I saw all the mistakes, I saw ... They weren't mistakes; I saw everything that I would have changed and I was embarrassed by it. I felt an embarrassment -- "How could I have done that? How could I have made shapes like that or done stuff like that?" It's taken several years to now look at it detached and say -- as you walk around the corner and a piece of it works with the road and the street, and it appears to have a relationship -- that I started to like it.

RSW: What's the status of the New York project?

FG: I don't really know. Tom Krens came to me with Bilbao and explained it all to me, and I thought he was nuts. I didn't think he knew what he was doing, and he pulled it off. So, I think he's Icarus and Phoenix all in one guy. (Laughter) He gets up there and then he ... comes back up. They're still talking about it. September 11 generated some interest in moving it over to Ground Zero, and I'm totally against that. I just feel uncomfortable talking about or building anything on Ground Zero I think for a long time.

RSW: The picture on the screen, is that Disney?

FG: Yeah.

RSW: How much further along is it than that, and when will that be finished?

FG: That will be finished in 2003 -- September, October -- and I'm hoping Kyu, and Herbie, and Yo-Yo and all those guys come play with us at that place. Luckily, today most of the people I'm working with are people I really like. Richard Koshalek is probably one of the main reasons that Disney Hall came to me. He's been a cheerleader for quite a long time. There aren't many people around that are really involved with architecture as clients. If you think about the world, and even just in this audience, most of us are involved with buildings. Nothing that you would call architecture, right? And so to find one, a guy like that, you hang on to him. He's become the head of Art Center, and there's a building by Craig Ellwood there. I knew Craig and respected him. They want to add to it and it's hard to add to a building like that -- it's a beautiful, minimalist, black steel building -- and Richard wants to add a library and more student stuff and it's a lot of acreage. I convinced him to let me bring in another architect from Portugal: Alvaro Siza.

RSW: Why did you want that?

FG: I knew you'd ask that question.

It was intuitive. (Laughter)

Alvaro Siza grew up and lived in Portugal and is probably considered the Portuguese main guy in architecture. I visited with him a few years ago and he showed me his early work, and his early work had a resemblance to my early work. When I came out of college, I started to try to do things contextually in Southern California, and you got into the logic of Spanish colonial tile roofs and things like that. I tried to understand that language as a beginning, as a place to jump off, and there was so much of it being done by spec builders and it was trivialized so much that it wasn't ... I just stopped. I mean, Charlie Moore did a bunch of it, but it didn't feel good to me. Siza, on the other hand, continued in Portugal where the real stuff was and evolved a modern language that relates to that historic language. And I always felt that he should come to Southern California and do a building. I tried to get him a couple of jobs and they didn't pan out. I like the idea of collaboration with people like that because it pushes you. I've done it with Claes Oldenburg and with Richard Serra, who doesn't think architecture is art. Did you see that thing? RSW: No. What did he say?

FG: He calls architecture "plumbing." (Laughter)

FG: Anyway, the Siza thing. It's a richer experience. It must be like that for Kyu doing things with musicians -- it's similar to that I would imagine -- where you ... huh?

Audience: Liquid architecture.

FG: Liquid architecture. (Laughter) Where you ... It's like jazz: you improvise, you work together, you play off each other, you make something, they make something. And I think for me, it's a way of trying to understand the city and what might happen in the city.

RSW: Is it going to be near the current campus? Or is it going to be down near ...

FG: No, it's near the current campus. Anyway, he's that kind of patron. It's not his money, of course. (Laughter)

RSW: What's his schedule on that?

FG: I don't know. What's the schedule, Richard? Richard Koshalek: [Unclear] starts from 2004.

FG: 2004. You can come to the opening. I'll invite you. No, but the issue of city building in democracy is interesting because it creates chaos, right? Everybody doing their thing makes a very chaotic environment, and if you can figure out how to work off each other -- if you can get a bunch of people who respect each other's work and play off each other, you might be able to create models for how to build sections of the city without resorting to the one architect. Like the Rockefeller Center model, which is kind of from another era.

RSW: I found the most remarkable thing. My preconception of Bilbao was this wonderful building, you go inside and there'd be extraordinary spaces. I'd seen drawings you had presented here at TED. The surprise of Bilbao was in its context to the city. That was the surprise of going across the river, of going on the highway around it, of walking down the street and finding it. That was the real surprise of Bilbao.

FG: But you know, Richard, most architects when they present their work -- most of the people we know, you get up and you talk about your work, and it's almost like you tell everybody you're a good guy by saying, "Look, I'm worried about the context, I'm worried about the city, I'm worried about my client, I worry about budget, that I'm on time." Blah, blah, blah and all that stuff. And it's like cleansing yourself so that you can ... by saying all that, it means your work is good somehow. And I think everybody -- I mean that should be a matter of fact, like gravity. You're not going to defy gravity. You've got to work with the building department. If you don't meet the budgets, you're not going to get much work. If it leaks -- Bilbao did not leak. I was so proud. (Laughter) The MIT project -- they were interviewing me for MIT and they sent their facilities people to Bilbao. I met them in Bilbao. They came for three days.

RSW: This is the computer building?

FG: Yeah, the computer building. They were there three days and it rained every day and they kept walking around -- I noticed they were looking under things and looking for things, and they wanted to know where the buckets were hidden, you know? People put buckets out ... I was clean. There wasn't a bloody leak in the place, it was just fantastic. But you've got to -- yeah, well up until then every building leaked, so this ... (Laughter)

RSW: Frank had a sort of ...

FG: Ask Miriam!

RW: ... sort of had a fame. His fame was built on that in L.A. for a while. (Laughter)

FG: You've all heard the Frank Lloyd Wright story, when the woman called and said, "Mr. Wright, I'm sitting on the couch and the water's pouring in on my head." And he said, "Madam, move your chair." (Laughter) So, some years later I was doing a building, a little house on the beach for Norton Simon, and his secretary, who was kind of a hell on wheels type lady, called me and said, "Mr. Simon's sitting at his desk and the water's coming in on his head." And I told her the Frank Lloyd Wright story.

RSW: Didn't get a laugh.

FG: No. Not now either. (Laughter)

But my point is that ... and I call it the "then what?" OK, you solved all the problems, you did all the stuff, you made nice, you loved your clients, you loved the city, you're a good guy, you're a good person ... and then what? What do you bring to it? And I think that's what I've always been interested in, is that -- which is a personal kind of expression. Bilbao, I think, shows that you can have that kind of personal expression and still touch all the bases that are necessary of fitting into the city. That's what reminded me of it. And I think that's the issue, you know; it's the "then what" that most clients who hire architects -- most clients aren't hiring architects for that. They're hiring them to get it done, get it on budget, be polite, and they're missing out on the real value of an architect.

RSW: At a certain point a number of years ago, people -- when Michael Graves was a fashion, before teapots ...

FG: I did a teapot and nobody bought it. (Laughter)

RSW: Did it leak?

FG: No. (Laughter)

RSW: ... people wanted a Michael Graves building. Is that a curse, that people want a Bilbao building?

FG: Yeah. Since Bilbao opened, which is now four, five years, both Krens and I have been called with at least 100 opportunities -- China, Brazil, other parts of Spain -- to come in and do the Bilbao effect. And I've met with some of these people. Usually I say no right away, but some of them come with pedigree and they sound well-intentioned and they get you for at least one or two meetings. In one case, I flew all the way to Malaga with a team because the thing was signed with seals and various very official seals from the city, and that they wanted me to come and do a building in their port. I asked them what kind of building it was. "When you get here we'll explain it." Blah, blah, blah. So four of us went. And they took us -- they put us up in a great hotel and we were looking over the bay, and then they took us in a boat out in the water and showed us all these sights in the harbor. Each one was more beautiful than the other. And then we were going to have lunch with the mayor and we were going to have dinner with the most important people in Malaga. Just before going to lunch with the mayor, we went to the harbor commissioner. It was a table as long as this carpet and the harbor commissioner was here, and I was here, and my guys. We sat down, and we had a drink of water and everybody was quiet. And the guy looked at me and said, "Now what can I do for you, Mr. Gehry?" (Laughter)

RSW: Oh, my God. FG: So, I got up. I said to my team, "Let's get out of here." We stood up, we walked out. They followed -- the guy that dragged us there followed us and he said, "You mean you're not going to have lunch with the mayor?" I said, "Nope." "You're not going to have dinner at all?" They just brought us there to hustle this group, you know, to create a project. And we get a lot of that. Luckily, I'm old enough that I can complain I can't travel. (Laughter) I don't have my own plane yet.

RSW: Well, I'm going to wind this up and wind up the meeting because it's been very long. But let me just say a couple words.

FG: Can I say something? Are you going to talk about me or you? (Laughter) (Applause)

RSW: Once a shit, always a shit!

FG: Because I want to get a standing ovation like everybody, so ...

RSW: You're going to get one! You're going to get one! (Laughter)

I'm going to make it for you!

FG: No, no. Wait a minute! (Applause)