You know, culture was born of the imagination, and the imagination -- the imagination as we know it -- came into being when our species descended from our progenitor, Homo erectus, and, infused with consciousness, began a journey that would carry it to every corner of the habitable world. For a time, we shared the stage with our distant cousins, Neanderthal, who clearly had some spark of awareness, but -- whether it was the increase in the size of the brain, or the development of language, or some other evolutionary catalyst -- we quickly left Neanderthal gasping for survival. By the time the last Neanderthal disappeared in Europe, 27,000 years ago, our direct ancestors had already, and for 5,000 years, been crawling into the belly of the earth, where in the light of the flickers of tallow candles, they had brought into being the great art of the Upper Paleolithic.

And I spent two months in the caves of southwest France with the poet Clayton Eshleman, who wrote a beautiful book called "Juniper Fuse." And you could look at this art and you could, of course, see the complex social organization of the people who brought it into being. But more importantly, it spoke of a deeper yearning, something far more sophisticated than hunting magic. And the way Clayton put it was this way. He said, "You know, clearly at some point, we were all of an animal nature, and at some point, we weren't." And he viewed proto-shamanism as a kind of original attempt, through ritual, to rekindle a connection that had been irrevocably lost. So, he saw this art not as hunting magic, but as postcards of nostalgia. And viewed in that light, it takes on a whole other resonance.

And the most amazing thing about the Upper Paleolithic art is that as an aesthetic expression, it lasted for almost 20,000 years. If these were postcards of nostalgia, ours was a very long farewell indeed. And it was also the beginning of our discontent, because if you wanted to distill all of our experience since the Paleolithic, it would come down to two words: how and why. And these are the slivers of insight upon which cultures have been forged. Now, all people share the same raw, adaptive imperatives. We all have children. We all have to deal with the mystery of death, the world that waits beyond death, the elders who fall away into their elderly years. All of this is part of our common experience, and this shouldn't surprise us, because, after all, biologists have finally proven it to be true, something that philosophers have always dreamt to be true. And that is the fact that we are all brothers and sisters. We are all cut from the same genetic cloth. All of humanity, probably, is descended from a thousand people who left Africa roughly 70,000 years ago.

But the corollary of that is that, if we all are brothers and sisters and share the same genetic material, all human populations share the same raw human genius, the same intellectual acuity. And so whether that genius is placed into -- technological wizardry has been the great achievement of the West -- or by contrast, into unraveling the complex threads of memory inherent in a myth, is simply a matter of choice and cultural orientation. There is no progression of affairs in human experience. There is no trajectory of progress. There's no pyramid that conveniently places Victorian England at the apex and descends down the flanks to the so-called primitives of the world. All peoples are simply cultural options, different visions of life itself. But what do I mean by different visions of life making for completely different possibilities for existence?

Well, let's slip for a moment into the greatest culture sphere ever brought into being by the imagination, that of Polynesia. 10,000 square kilometers, tens of thousands of islands flung like jewels upon the southern sea. I recently sailed on the Hokulea, named after the sacred star of Hawaii, throughout the South Pacific to make a film about the navigators. These are men and women who, even today, can name 250 stars in the night sky. These are men and women who can sense the presence of distant atolls of islands beyond the visible horizon, simply by watching the reverberation of waves across the hull of their vessel, knowing full well that every island group in the Pacific has its unique refractive pattern that can be read with the same perspicacity with which a forensic scientist would read a fingerprint. These are sailors who in the darkness, in the hull of the vessel, can distinguish as many as 32 different sea swells moving through the canoe at any one point in time, distinguishing local wave disturbances from the great currents that pulsate across the ocean, that can be followed with the same ease that a terrestrial explorer would follow a river to the sea. Indeed, if you took all of the genius that allowed us to put a man on the moon and applied it to an understanding of the ocean, what you would get is Polynesia.

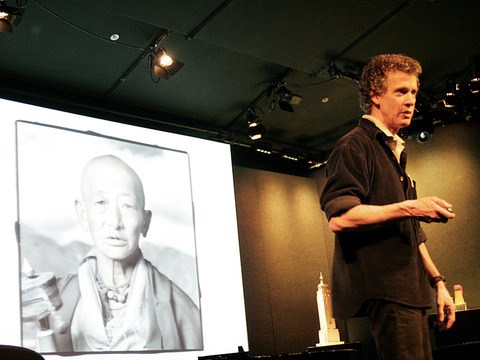

And if we slip from the realm of the sea into the realm of the spirit of the imagination, you enter the realm of Tibetan Buddhism. And I recently made a film called "The Buddhist Science of the Mind." Why did we use that word, science? What is science but the empirical pursuit of the truth? What is Buddhism but 2,500 years of empirical observation as to the nature of mind? I travelled for a month in Nepal with our good friend, Matthieu Ricard, and you'll remember Matthieu famously said to all of us here once at TED, "Western science is a major response to minor needs." We spend all of our lifetime trying to live to be 100 without losing our teeth. The Buddhist spends all their lifetime trying to understand the nature of existence.

Our billboards celebrate naked children in underwear. Their billboards are manuals, prayers to the well-being of all sentient creatures. And with the blessing of Trulshik Rinpoche, we began a pilgrimage to a curious destination, accompanied by a great doctor. And the destination was a single room in a nunnery, where a woman had gone into lifelong retreat 55 years before. And en route, we took darshan from Rinpoche, and he sat with us and told us about the Four Noble Truths, the essence of the Buddhist path. All life is suffering. That doesn't mean all life is negative. It means things happen. The cause of suffering is ignorance. By that, the Buddha did not mean stupidity; he meant clinging to the illusion that life is static and predictable. The third noble truth said that ignorance can be overcome. And the fourth and most important, of course, was the delineation of a contemplative practice that not only had the possibility of a transformation of the human heart, but had 2,500 years of empirical evidence that such a transformation was a certainty.

And so, when this door opened onto the face of a woman who had not been out of that room in 55 years, you did not see a mad woman. You saw a woman who was more clear than a pool of water in a mountain stream. And of course, this is what the Tibetan monks told us. They said, at one point, you know, we don't really believe you went to the moon, but you did. You may not believe that we achieve enlightenment in one lifetime, but we do. And if we move from the realm of the spirit to the realm of the physical, to the sacred geography of Peru -- I've always been interested in the relationships of indigenous people that literally believe that the Earth is alive, responsive to all of their aspirations, all of their needs. And, of course, the human population has its own reciprocal obligations.

I spent 30 years living amongst the people of Chinchero and I always heard about an event that I always wanted to participate in. Once each year, the fastest young boy in each hamlet is given the honor of becoming a woman. And for one day, he wears the clothing of his sister and he becomes a transvestite, a waylaka. And for that day, he leads all able-bodied men on a run, but it's not your ordinary run. You start off at 11,500 feet. You run down to the base of the sacred mountain, Antakillqa. You run up to 15,000 feet, descend 3,000 feet. Climb again over the course of 24 hours. And of course, the waylakama spin, the trajectory of the route, is marked by holy mounds of Earth, where coke is given to the Earth, libations of alcohol to the wind, the vortex of the feminine is brought to the mountaintop. And the metaphor is clear: you go into the mountain as an individual, but through exhaustion, through sacrifice, you emerge as a community that has once again reaffirmed its sense of place in the planet. And at 48, I was the only outsider ever to go through this, only one to finish it. I only managed to do it by chewing more coca leaves in one day than anyone in the 4,000-year history of the plant.

But these localized rituals become pan-Andean, and these fantastic festivals, like that of the Qoyllur Rit'i, which occurs when the Pleiades reappear in the winter sky. It's kind of like an Andean Woodstock: 60,000 Indians on pilgrimage to the end of a dirt road that leads to the sacred valley, called the Sinakara, which is dominated by three tongues of the great glacier. The metaphor is so clear. You bring the crosses from your community, in this wonderful fusion of Christian and pre-Columbian ideas. You place the cross into the ice, in the shadow of Ausangate, the most sacred of all Apus, or sacred mountains of the Inca. And then you do the ritual dances that empower the crosses.

Now, these ideas and these events allow us even to deconstruct iconic places that many of you have been to, like Machu Picchu. Machu Picchu was never a lost city. On the contrary, it was completely linked in to the 14,000 kilometers of royal roads the Inca made in less than a century. But more importantly, it was linked in to the Andean notions of sacred geography. The intiwatana, the hitching post to the sun, is actually an obelisk that constantly reflects the light that falls on the sacred Apu of Machu Picchu, which is Sugarloaf Mountain, called Huayna Picchu. If you come to the south of the intiwatana, you find an altar. Climb Huayna Picchu, find another altar. Take a direct north-south bearing, you find to your astonishment that it bisects the intiwatana stone, goes to the skyline, hits the heart of Salcantay, the second of the most important mountains of the Incan empire. And then beyond Salcantay, of course, when the southern cross reaches the southernmost point in the sky, directly in that same alignment, the Milky Way overhead. But what is enveloping Machu Picchu from below? The sacred river, the Urubamba, or the Vilcanota, which is itself the Earthly equivalent of the Milky Way, but it's also the trajectory that Viracocha walked at the dawn of time when he brought the universe into being. And where does the river rise? Right on the slopes of the Koariti.

So, 500 years after Columbus, these ancient rhythms of landscape are played out in ritual. Now, when I was here at the first TED, I showed this photograph: two men of the Elder Brothers, the descendants, survivors of El Dorado. These, of course, are the descendants of the ancient Tairona civilization. If those of you who are here remember that I mentioned that they remain ruled by a ritual priesthood, but the training for the priesthood is extraordinary. Taken from their families, sequestered in a shadowy world of darkness for 18 years -- two nine-year periods deliberately chosen to evoke the nine months they spend in the natural mother's womb. All that time, the world only exists as an abstraction, as they are taught the values of their society. Values that maintain the proposition that their prayers, and their prayers alone, maintain the cosmic balance. Now, the measure of a society is not only what it does, but the quality of its aspirations.

And I always wanted to go back into these mountains, to see if this could possibly be true, as indeed had been reported by the great anthropologist, Reichel-Dolmatoff. So, literally two weeks ago, I returned from having spent six weeks with the Elder Brothers on what was clearly the most extraordinary trip of my life. These really are a people who live and breathe the realm of the sacred, a baroque religiosity that is simply awesome. They consume more coca leaves than any human population, half a pound per man, per day. The gourd you see here is -- everything in their lives is symbolic. Their central metaphor is a loom. They say, "Upon this loom, I weave my life." They refer to the movements as they exploit the ecological niches of the gradient as "threads." When they pray for the dead, they make these gestures with their hands, spinning their thoughts into the heavens.

You can see the calcium buildup on the head of the poporo gourd. The gourd is a feminine aspect; the stick is a male. You put the stick in the powder to take the sacred ashes -- well, they're not ashes, they're burnt limestone -- to empower the coca leaf, to change the pH of the mouth to facilitate the absorption of cocaine hydrochloride. But if you break a gourd, you cannot simply throw it away, because every stroke of that stick that has built up that calcium, the measure of a man's life, has a thought behind it. Fields are planted in such an extraordinary way, that the one side of the field is planted like that by the women. The other side is planted like that by the men. Metaphorically, you turn it on the side, and you have a piece of cloth. And they are the descendants of the ancient Tairona civilization, the greatest goldsmiths of South America, who in the wake of the conquest, retreated into this isolated volcanic massif that soars to 20,000 feet above the Caribbean coastal plain.

There are four societies: the Kogi, the Wiwa, the Kankwano and the Arhuacos. I traveled with the Arhuacos, and the wonderful thing about this story was that this man, Danilo Villafane -- if we just jump back here for a second. When I first met Danilo, in the Colombian embassy in Washington, I couldn't help but say, "You know, you look a lot like an old friend of mine." Well, it turns out he was the son of my friend, Adalberto, from 1974, who had been killed by the FARC. And I said, "Danilo, you won't remember this, but when you were an infant, I carried you on my back, up and down the mountains." And because of that, Danilo invited us to go to the very heart of the world, a place where no journalist had ever been permitted. Not simply to the flanks of the mountains, but to the very iced peaks which are the destiny of the pilgrims.

And this man sitting cross-legged is now a grown-up Eugenio, a man who I've known since 1974. And this is one of those initiates. No, it's not true that they're kept in the darkness for 18 years, but they are kept within the confines of the ceremonial men's circle for 18 years. This little boy will never step outside of the sacred fields that surround the men's hut for all that time, until he begins his journey of initiation. For that entire time, the world only exists as an abstraction, as he is taught the values of society, including this notion that their prayers alone maintain the cosmic balance. Before we could begin our journey, we had to be cleansed at the portal of the Earth. And it was extraordinary to be taken by a priest. And you see that the priest never wears shoes because holy feet -- there must be nothing between the feet and the Earth for a mamo. And this is actually the place where the Great Mother sent the spindle into the world that elevated the mountains and created the homeland that they call the heart of the world.

We traveled high into the paramo, and as we crested the hills, we realized that the men were interpreting every single bump on the landscape in terms of their own intense religiosity. And then of course, as we reached our final destination, a place called Mamancana, we were in for a surprise, because the FARC were waiting to kidnap us. And so we ended up being taken aside into these huts, hidden away until the darkness. And then, abandoning all our gear, we were forced to ride out in the middle of the night, in a quite dramatic scene. It's going to look like a John Ford Western. And we ran into a FARC patrol at dawn, so it was quite harrowing. It will be a very interesting film. But what was fascinating is that the minute there was a sense of dangers, the mamos went into a circle of divination.

And of course, this is a photograph literally taken the night we were in hiding, as they divine their route to take us out of the mountains. We were able to, because we had trained people in filmmaking, continue with our work, and send our Wiwa and Arhuaco filmmakers to the final sacred lakes to get the last shots for the film, and we followed the rest of the Arhuaco back to the sea, taking the elements from the highlands to the sea. And here you see how their sacred landscape has been covered by brothels and hotels and casinos, and yet, still they pray. And it's an amazing thing to think that this close to Miami, two hours from Miami, there is an entire civilization of people praying every day for your well-being. They call themselves the Elder Brothers. They dismiss the rest of us who have ruined the world as the Younger Brothers. They cannot understand why it is that we do what we do to the Earth.

Now, if we slip to another end of the world, I was up in the high Arctic to tell a story about global warming, inspired in part by the former Vice President's wonderful book. And what struck me so extraordinary was to be again with the Inuit -- a people who don't fear the cold, but take advantage of it. A people who find a way, with their imagination, to carve life out of that very frozen. A people for whom blood on ice is not a sign of death, but an affirmation of life. And yet tragically, when you now go to those northern communities, you find to your astonishment that whereas the sea ice used to come in in September and stay till July, in a place like Kanak in northern Greenland, it literally comes in now in November and stays until March. So, their entire year has been cut in half.

Now, I want to stress that none of these peoples that I've been quickly talking about here are disappearing worlds. These are not dying peoples. On the contrary, you know, if you have the heart to feel and the eyes to see, you discover that the world is not flat. The world remains a rich tapestry. It remains a rich topography of the spirit. These myriad voices of humanity are not failed attempts at being new, failed attempts at being modern. They're unique facets of the human imagination. They're unique answers to a fundamental question: what does it mean to be human and alive? And when asked that question, they respond with 6,000 different voices. And collectively, those voices become our human repertoire for dealing with the challenges that will confront us in the ensuing millennia.

Our industrial society is scarcely 300 years old. That shallow history shouldn't suggest to anyone that we have all of the answers for all of the questions that will confront us in the ensuing millennia. The myriad voices of humanity are not failed attempts at being us. They are unique answers to that fundamental question: what does it mean to be human and alive? And there is indeed a fire burning over the Earth, taking with it not only plants and animals, but the legacy of humanity's brilliance.

Right now, as we sit here in this room, of those 6,000 languages spoken the day that you were born, fully half aren't being taught to children. So, you're living through a time when virtually half of humanity's intellectual, social and spiritual legacy is being allowed to slip away. This does not have to happen. These peoples are not failed attempts at being modern -- quaint and colorful and destined to fade away as if by natural law.

In every case, these are dynamic, living peoples being driven out of existence by identifiable forces. That's actually an optimistic observation, because it suggests that if human beings are the agents of cultural destruction, we can also be, and must be, the facilitators of cultural survival.

Thank you very much.