As a child, I was raised by native Hawaiian elders -- three old women who took care of me while my parents worked. The year is 1963. We're at the ocean. It's twilight. We're watching the rising of the stars and the shifting of the tides. It's a stretch of beach we know so well. The smooth stones on the sand are familiar to us. If you saw these women on the street in their faded clothes, you might dismiss them as poor and simple. That would be a mistake. These women are descendants of Polynesian navigators, trained in the old ways by their elders, and now they're passing it on to me. They teach me the names of the winds and the rains, of astronomy according to a genealogy of stars. There's a new moon on the horizon. Hawaiians say it's a good night for fishing. They begin to chant.

[Hawaiian chant]

When they finish, they sit in a circle and ask me to come to join them. They want to teach me about my destiny. I thought every seven-year-old went through this. (Laughter) "Baby girl, someday the world will be in trouble. People will forget their wisdom. It will take elders' voices from the far corners of the world to call the world into balance. You will go far away. It will sometimes be a lonely road. We will not be there. But you will look into the eyes of seeming strangers, and you will recognize your ohana, your family. And it will take all of you. It will take all of you." These words, I hold onto all my life. Because the idea of doing it alone terrifies me.

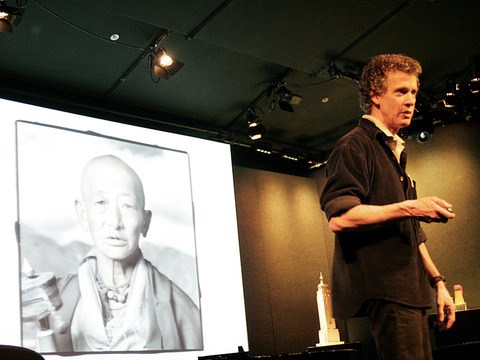

The year is 2007. I'm on a remote island in Micronesia. Satawal is one half-mile long by one mile wide. It's the home of my mentor. His name is Pius Mau Piailug. Mau is a palu, a navigator priest. He's also considered the greatest wave finder in the world. There are fewer than a handful of palu left on this island. Their tradition is so extraordinary that these mariners sailed three million square miles across the Pacific without the use of instruments. They could synthesize patterns in nature using the rising and setting of stars, the sequence and direction of waves, the flight patterns of certain birds. Even the slightest hint of color on the underbelly of a cloud would inform them and help them navigate with the keenest accuracy.

When Western scientists would join Mau on the canoe and watch him go into the hull, it appeared that an old man was going to rest. In fact, the hull of the canoe is the womb of the vessel. It is the most accurate place to feel the rhythm and sequence and direction of waves. Mau was, in fact, gathering explicit data using his entire body. It's what he had been trained to do since he was five years old. Now science may dismiss this methodology, but Polynesian navigators use it today because it provides them an accurate determination of the angle and direction of their vessel.

The palu also had an uncanny ability to forecast weather conditions days in advance. Sometimes I'd be with Mau on a cloud-covered night and we'd sit at the easternmost coast of the island, and he would look out, and then he would say, "Okay, we go." He saw that first glint of light -- he knew what the weather was going to be three days from now.

Their achievements, intellectually and scientifically, are extraordinary, and they are so relevant for these times that we are in when we are riding out storms. We are in such a critical moment of our collective history. They have been compared to astronauts -- these elder navigators who sail vast open oceans in double-hulled canoes thousands of miles from a small island. Their canoes, our rockets; their sea, our space. The wisdom of these elders is not a mere collection of stories about old people in some remote spot. This is part of our collective narrative. It's humanity's DNA. We cannot afford to lose it.

The year is 2010. Just as the women in Hawaii that raised me predicted, the world is in trouble. We live in a society bloated with data, yet starved for wisdom. We're connected 24/7, yet anxiety, fear, depression and loneliness is at an all-time high. We must course-correct. An African shaman said, "Your society worships the jester while the king stands in plain clothes." The link between the past and the future is fragile. This I know intimately, because even as I travel throughout the world to listen to these stories and record them, I struggle. I am haunted by the fact that I no longer remember the names of the winds and the rains.

Mau passed away five months ago, but his legacy and lessons live on. And I am reminded that throughout the world there are cultures with vast sums of knowledge in them, as potent as the Micronesian navigators, that are going dismissed, that this is a testament to brilliant, brilliant technology and science and wisdom that is vanishing rapidly. Because when an elder dies a library is burned, and throughout the world, libraries are ablaze.

I am grateful for the fact that I had a mentor like Mau who taught me how to navigate. And I realize through a lesson that he shared that we continue to find our way. And this is what he said: "The island is the canoe; the canoe, the island." And what he meant was, if you are voyaging and far from home, your very survival depends on everyone aboard. You cannot make the voyage alone, you were never meant to. This whole notion of every man for himself is completely unsustainable. It always was.

So in closing I would offer you this: The planet is our canoe, and we are the voyagers. True navigation begins in the human heart. It's the most important map of all. Together, may we journey well.

(Applause)