Chris Anderson: Hello, I am Chris Anderson. Welcome to The TED Interview. This is the podcast series where I get to sit down with a TED speaker and dive much deeper into their ideas than was possible during their short TED talk.

(Music)

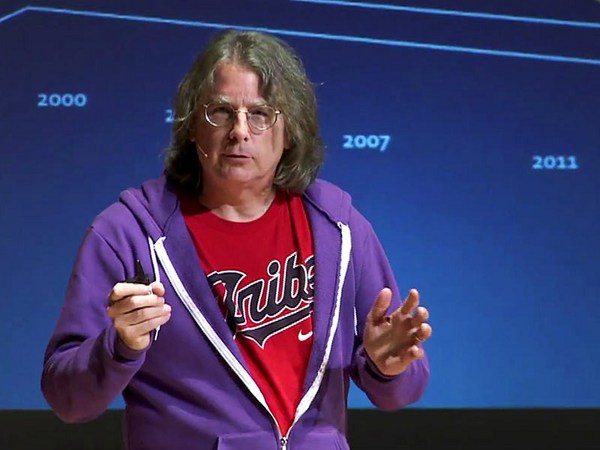

Now then, this is a special episode that we're releasing in advance of season two of our show, which premieres on May 15. We have a really exciting list of speakers coming up, starting with Bill Gates, Susan Cain, Tim Ferris. But this episode is a tasty appetizer. It was recorded live at the TED conference that we just held in Vancouver. I sat down with Roger McNamee, who's been an influential voice in technology for many years, been coming to TED for many years, actually. But recently, he has turned into an outspoken critic of some of the big tech companies. In fact, this spring, he published a searing critique of Facebook and his one-time friend, Mark Zuckerberg, the book cleverly titled "Zucked." So Roger has had something of an inside view of what he considers to be an unfolding catastrophe, and has teamed up with other critics to press for radical changes, including government regulation, and even antitrust action. So this was a fantastic chance to really dig into two of the biggest questions of the moment. Namely, how did the big, beautiful dream of technology connecting the world go so wrong? And what on earth can we do about it? In the audience were several leading technology figures, and they ended up chipping in themselves, toward the end. Here is how it all went down.

(Applause)

Roger McNamee, welcome to The TED Interview.

Roger McNamee: What an honor, great to be here, Chris.

CA: Just to summarize it, a little more than a decade ago, you met Mark Zuckerberg, you persuaded him not to take a billion-dollar offer, or encouraged him not to, you introduced him to Sheryl Sandberg and urged him to hire her. You became an investor in Facebook and a passionate believer in the company. You stepped back a bit from direct involvement as being a direct adviser to Mark, and watched, and then this spring, you came out with a book, and the title of the book was not "My Brilliant Friend, Mark Zuckerberg." It was, "Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe." At first glance, that seems like a pretty major betrayal. And your contention is that it's not you who did the betraying.

RM: Well, here's what I believe -- and I think I can always be criticized -- but when I met Mark, he was 22. I thought he was different from the other entrepreneurs of that era. If you think about it, the big success stories out of Silicon Valley over the past dozen years have included companies like Uber and Airbnb and Lyft, companies like Spotify, which is not based there, but comes out of that same ecosystem. And there were two core driving principles. One was that laws didn't apply. So you had a set of people whose basic principle was that the laws that govern the economy in their sector didn't apply. That would be Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, or ones who said, "I can develop an information advantage over one of the other constituencies in my ecosystem," which would be Spotify, the fintech companies, and also Uber and Lyft, relative to drivers. I thought Mark was different than that. And I was a huge, huge believer in the company. And when I retired from the business at the end of 2015, and I started to see things going wrong, I was shocked because I really thought Facebook, at its core, had a better value system, and that the product was designed to be, you know, both fun and, at least, not harmful.

CA: What was the first thing that gave you pause for thought?

RM: There were two that happened right in a row. The first was during the 2016 Democratic primary in New Hampshire, when I saw a Facebook group associated notionally with the Bernie Sanders campaign distributing misogynistic memes, and they were spreading virally among my friend group, in a way that suggests that somebody was spending money to make them happen. To get people into the group. And then, the second thing was just a couple months later. A corporation was expelled from Facebook for using the ad tools to get data about anyone who expressed an interest in Black Lives Matter. And they were then selling that data to police departments. Now Facebook did the right thing, they expelled them, but the damage had been done. These people's civil rights had been violated. And those two things really set me back.

CA: And so, did you raise your concerns with Facebook, to try and find out what had happened?

RM: At the beginning, I didn't have enough data. And then, almost immediately, the United Kingdom had its referendum on leaving the European Union, Brexit. And Brexit was when I started to see, "Oh my God, the ad tools, the same thing that makes posts viral, can be used in an electoral context." And the side with a more inflammatory message would get a huge uplift, right? That's when I began to reach out to people. And I made a ... I lobbed messages into a lot of different people, and I didn't have data, and you know how data-driven our world is, and so, people were kind of going, "Roger, those things can't be related." Then in October, two things happened that forced me to go into action. The first is Housing and Urban Development cited Facebook because the ad tools allowed discrimination in housing, in violation of the Fair Housing Act. And immediately after that, we heard that our intelligence agencies said the Russians were trying to interfere in the election. That is when I reached out to Mark and Sheryl, at the end of October of 2016.

CA: The thing that's puzzling about this is what to make of why this happened. I mean, one view would be that Facebook were excited to let their platform be used in this way because they made a fortune from it. When you actually look at the numbers, if that was their intention, they shockingly undercharged, because I think the Russians spent -- the number I saw was like 100,000 dollars or less. For that, they reached more than 100 million --

RM: 126 million.

CA: ... Americans.

RM: In an election where 137 million people voted.

CA: That is either the most cost-effective advertizing ever invented in the history of the planet, or a complete screw up. There's no scenario that you think that that was intended --

RM: Facebook is the greatest advertizing platform ever invented. My sense is that Facebook provides any marketer with targeting that is better and more cost-effective than anything that ever preceded it. There's a reason why the stock's done so well. And there's a reason why I was such a big fan. It seemed to be something that didn't hurt anybody. The problem here, Chris, and I think the issue with the Russians, is that the way the incentives work -- and this is not a Facebook issue, this is the Valley and candidly, the whole US economy -- which, there really weren't any rules. And so, the notion was, get rid of all the friction, and grow as rapidly to global scale as you possibly can. And in that context, everything was automated. And it was no one's job to ask the question, "What could go wrong?"

CA: Indeed. So it seems like at the heart of this, the origination of this is basically a reckless naivete. It's a belief that, "Look, people are basically good, our mission is to connect the world. If we connect the world as fast as the heck we can, yes, we'll make money from this stuff, but it's going to be fundamentally good." It just wasn't foreseen --

RM: They got to 1.7 billion monthly users before anything really bad showed up on the platform. Listen, I say this as somebody who is currently a critic, but you still have to admire how extraordinary the accomplishment was to get to 1.7 billion before anything went wrong. The problem was once you passed that threshold, all of a sudden, things started to go wrong all over the place, and their basic business practices get looked at in a completely different light, and you see that, "Oh, wait a minute, the cost of getting here is higher than it looks."

CA: A bunch of things happened, where they were basically exploited by bad actors. So, there's the Cambridge Analytica story, where data was sold "innocently" for academic purposes, and then abused. Should Facebook have seen that coming? Possibly. But at some point, they must have had this sickening realization, "Holy crap, look what's happened. Even if money was their motive, they got almost no money for this. But they allowed themselves to be exploited to a spectacular degree.

RM: The way I look at that experience was, when Zynga came along with FarmVille and the poker game, they essentially reverse engineered Facebook, and they figured out a way to get at friends' lists. And they began a campaign of sharing the data. The Federal Trade Commission goes, "No." They do a consent decree in 2011 that basically says there has to be informed prior consent before anybody's data is shared. My understanding -- I can't prove this -- my understanding is that Facebook essentially moved forward as though there was no consent decree. And continued to operate through 2014 with that basic notion of, if there was a way to gain competitive advantage by the trading of user data, they were going to do it. And privacy was not a consideration that was in the discussion.

CA: What should have happened then? Because suddenly, it became very, very apparent that there'd been this horrifying hack of enormous consequence. What should have happened at that point?

RM: Except, not a hack. They were using the tools the way they were designed. Essentially, this was the unintended consequence of a well-intended strategy, done by really bad actors who had a really clever strategy. So when I went to them on the 30th of October, I sent this op-ed I was drafting --

CA: The 30th of October 2016?

RM: 2016, so it's nine days before the election. It basically focuses on the issue with the Bernie Sanders campaign, it focuses on the Black Lives Matter, on Brexit and on the housing urban development. And I basically say, "Look, guys, I think there is a problem with the algorithms, there's a problem with the business model, you've got to get on top of this. I'm not thinking it's going to affect the outcome of the 2016 election, I'm just reaching out to my friends with what I perceive as this failure mode that's suddenly being exposed." And their response, which, under the context was maybe understandable, was, "Roger, these are just isolated things. We appreciate you reaching out, we value your input, we're going to turn you over to Dan Rose, who's going to help you figure out if there's really something here." We had these conversations, then the US election happens, and I go to Dan, I say, "Dan, you've got Brexit, you've got the US election, where you are potentially involved in the outcome. You've got at least two big civil rights things that I can see. You have got to do what Johnson & Johnson did, when somebody put poison in bottles of Tylenol, in Chicago, Illinois, in 1982." Which is, they took every bottle off of every shelf, without being asked -- like, instantly. And they didn't put them back until they invented tamper-proof packaging. My point was, you have to leap to the defense of the people who use your product. This is what Boeing should have done with the 737 MAX. You do not want to be forced to do the right thing, because it kills your brand. And I said, you guys have a trust business. And I spent three months -- three months -- pleading with Dan to do the right thing.

CA: So they could have said, and in your view, should have said, "Alert, world, alert, American people. We've noticed that something terrible has happened on our platform, a huge number of ads have gone out there that frankly are not fact-based. Here are the steps we're doing to shut it down. Meanwhile, beware." That they could have said that and should have said that.

RM: My belief was, the simple thing to do was to send an email to every single person touched by the Russian interference, the 126 million people on Facebook, the 20 million on Instagram, saying, "We really apologize, but the Russians have manipulated the election in the United States, have interfered in it, and you are affected. Here are all the ads you saw -- every one of these was not authentic." And that might have worked. It might not have worked, but it would have been better than what they did.

CA: If you put yourself in Zuck and Sheryl's shoes at that point, there you are, you've built this extraordinary company in record time, you're really considered, around the world, in the most idealistic terms by so many people. Your whole self-narrative is, "This is an exceptional organization. Fundamentally, our interests are aligned with a better world." The thought of going public with something that could slash the value of the company, could scare away a bunch of users, that would, at the very least, make you sick -- I can just about understand why someone would say, "This can't be right, let's wait, let's slow down, maybe we aren't understanding this the full way, maybe it will go away." Can you understand why that might happen?

RM: Definitely! What I asked them to do was to do that investigation -- which apparently, they did do. By the summer of 2017, they for sure knew the dimensions of the problem. And they still tried to brazen their way through it. And my simple point to them was, "If I'm right, this is not going to end well. You should protect your brand, protect your reputation."

CA: And I'm sure if they had their time over, they would probably agree that "We screwed up, we absolutely should have got ahead of this." And I think it's fair to say that now, the company has taken at least some steps.

RM: Oh, for sure.

CA: Like we heard on Monday, Carole Cadwalladr's -- who's here in the audience -- extraordinary talk about horrifying ads that were placed during the Brexit campaign that were never fully accounted for. A Facebook employee spoke to me afterwards and said that may have been true then. Now, it is impossible to buy political ads in that way. Do you agree that at least with respect to this specific case, that they have taken some preventative measures?

RM: They have. But what they've done is to protect against the repeat of 2016 without thinking about the dynamic system that is Facebook, and how many other ways there are to accomplish that same thing. So here's what I give Mark enormous credit for. Mark is out, speaking publicly, which is not a natural place for him, and I really applaud that. I wish Google were as engaged in this conversation as Mark is. I believe Mark wants to solve this problem. What I'm afraid is that the underlying business model is the root cause.

CA: It seems to be possible to imagine a business model that is based on advertising, but that says you can't place misleading political ads. That that in itself would not cripple the business model, and that's what they have sought, at least, to do, is to put strong limits on the types of political ads that could be placed now.

RM: Yeah, except it's really hard to monitor it, because the only people who see the ads are the people intended to receive it. So you have this issue, and this is what I think actually happened in 2016, where they picked these three groups: suburban white women, people of color and young people, and they essentially concocted messages that would suppress the vote. And in an election where 77,800 people in three states decided the outcome, it is not at all inconceivable that the Trump election campaign over Facebook played a huge role in deciding the outcome. And what I'm saying here is that if we look at the Russian part of it, stamping that out, stamping out foreign engagement in our elections is really essential. But I think it's just as important to prevent manipulation domestically that is designed to, you know, discourage people from voting, or whatever. You can say, "Well, there's always been voter suppression," I'm going, "But there have never been tools like this before." And I think you just have to step back and have the debate about what is democracy? How important is it to get everybody to be registered? How important is it to get everybody to vote? How important is it to have a level playing field, where, what I would point out, Chris, is that there was roughly a 17-1 advantage to Trump's advertising on Facebook over Clinton's, in part because the nature of the message was perfectly tuned to its audience; it was much more viral. And I don't want to relitigate 2016. 2016 is done, OK? What I'm worried about is that anybody can do that. Some guy at a school board in California hired an Israeli firm to try to do it in a school board election. I mean, it's really nutso how easy this stuff is to do. And again, Facebook didn't do this on purpose. But they created the world's greatest advertising platform. When you have that, it's vulnerable.

CA: So, Roger, you would argue that just for democracy, at the very least, there should be some restriction or compulsion for any company in the case of political advertising -- that can't be done in the dark.

RM: I agree.

CA: Even if you're going to target people, at the very least, the ads that are out there need to be out there, that companies shouldn't hold the secret. That, to me, sounds like a pretty reasonable point of view. Does anyone agree with that? No one agrees with that.

Audience: Why allow them?

CA: Someone's saying, "Why allow them at all?" So we had lukewarm approval of the last question. What I'm hearing is, what about this as an alternative, to say, money corrupts politics. We just should not allow political ads on social networks.

(Applause)

OK, it's a little warmer. I'd love us to move on from the direct political question to some of the other issues that people talk about. So, talk about outrage and filter bubbles, because I know this was another earlier worry you had about Facebook.

RM: One of the things that Tristan Harris taught me early on, was that smart phones changed marketing in a really profound way. Because historically, if you go back 100 years, people have used persuasion to get people's attention. But when you put it on a smart phone, you can target it individually. So Facebook today is 2.5 billion monthly users, which means 2.5 billion "Truman Shows." Each person can have their own reality. When I was a kid, there was a filter bubble in the United States called network television. Everyone my age watched the Kennedy funeral, the Beatles on Ed Sullivan and then the moon landing. We had Walter Cronkite, who changed our view of the Vietnam War, like, as a country, all at once, and the thing people complained about in that filter bubble was conformity. Now what you have with smart phones is you can now target each person individually. The initial business was targeted ads to pay for the business, but then they got to this notion of behavioral prediction. Facebook, Google and other people in this ad model, they're selling behavioral predictions to advertisers, because if you know that somebody's only two steps from buying a car, that ad's worth wildly more than if they're 20 steps away, right? So the closer you are to the prediction of where they are in that purchase process, the more valuable the ad is. So they're in behavioral prediction. But to make that work, they have to get past our public face. We all have this thing that makes us more alike when we're in groups. They want to find out, "How do you react if I show you something that's anti-Semitic? How do you react if I show you hate speech? How do you react if I show you violence? How do you react if I show you something that makes everyone else afraid?" From their point of view, it doesn't matter which way you react, but they've got to get through that filter. But I worry that the economic incentives right now are misaligned.

CA: You and I, we both know lots of people working for tech companies. Do you think that a significant proportion of them are thinking there, saying, "Ha ha, we've cracked it. We know how to make a ton of money. If we can just dial up the outrage among our users, imagine how many millions of people are going to flock to our platform and stay, and imagine the amount of advertizing we can sell them, let's do that."

RM: I don't think they think that way at all. I think they look at this, and they're engineers, and their job is to increase engagement, so they're going to promote whatever does it. If tomorrow morning, pictures of basset hounds promoted the most engagement, that's what they would be putting on everybody's feed. But that isn't what works. The other stuff works, and so naturally, as an engineer, you're always fine-tuning. And remember, nobody sees the whole picture. There are hundreds, maybe thousands of people working in these algorithms, and they each have one teeny little piece. Seeing the whole picture is really hard.

CA: But the way this is portrayed often, now, in the media, and in the public who's getting really angry about this, is that this is some intentional conspiracy by evil Silicon Valley. And the way I see it, this is an example of AI gone amok. You know, Nick Bostrom used to write about, the problem with AI is that it may have different goals from us. If you build an AI to make paper clips, and say, "Make as many as you can," and you give it enough intelligence, you will turn around one day, and then suddenly see that it's munched up New York City to turn it into paper clips, because you forgot to say, "Don't do that." By marketing attention and trying to build an attention economy, the start point, I think, for so much of Silicon Valley is, humans are basically good; if we give people a voice, if we give people a choice, they're going to teach each other, the world will get better, the truth will just be a click away -- even if someone does something mean, the crowd will correct them. And they missed what every tabloid publisher has known for 100 years. Which is, the way to get circulation, if that's your goal, is to be gory, to be dramatic, to be sexual, to put all the outrage out there. Facebook, and to some extent Twitter and Google, have turned us all into Rupert Murdochs, and into sort of, saying, "Wow, we can be our own tabloid publisher! Look at all the attention we can get by forgetting reason, by maximizing for each other's lizard brains." We've created an internet of lizard brains.

RM: I totally agree with that. If you read the book, one of the things you'll discover is I don't have anything unkind to say about any of the people. Not Mark, not Sheryl, not the people working at these companies. I believe this is a cultural problem that took place not just in Silicon Valley, but across the whole country. Think about this -- there's a local bank in my community called Wells Fargo. They got busted for taking money, essentially, from millions of their account holders. Nobody got punished for it. The banks got busted in 2008 for blowing up the entire economy -- nobody got punished for it. We live in a time where there are no rules and there's no enforcement, and these are really smart people who saw all this unclaimed data, and all this unclaimed opportunity and at the beginning, it seemed to throw off nothing but goodness, right? And by the time the bad stuff hit, we were so deep into it that it was really hard to reverse field. I get all that -- that doesn't mean we should ignore it.

CA: But if for a moment, we change the conversation from being, "Look how evil Silicon Valley has become," to being, "Holy crap, this is a massive screwup." Then the conversation becomes, "Is there a design fix?" I personally believe there are thousands of people in these companies right now, trying to figure out how the hell we get around this. And Tristan Harris himself has come up with these principles of humane design, where the goal is, instead of just maximizing attention, how do you create value, how do you make someone go, "I learned something, this was special." Here's my question to you. If Mark and Sheryl had two choices in front of them -- one, where they make a lot less money, but they still have a profitable company, but they have a much healthier ecosystem, where people aren't so motivated to amplify lizard-brain material, and are more motivated to be cross-partisan and so forth. Do you think they would take that choice?

RM: I surely hope they would. And that was the choice that I originally went to them with, and where I've carefully tried to position myself in this place of talking about business models. Because, to your point about design, you know, I don't think you can just fix this. Mark's solution to almost everything has been more code, more AI. The problem is that once people have a preference bubble, which is when they actually believe in anti-vax, when they actually believe that climate change is nonsense, when they're in that point, there's no technology fix. That's a human thing. A lot of this is about face-to-face and getting together with people and bridging gaps. And I think it has to start with the people who use the products. At the end of the day, we have been willing to accept the deal that we do not understand. The actual thing that's going on inside these companies is not that we're giving a little bit of personal data -- they're getting better ad targeting. There is way more going on here than that. And the stuff that's going beyond that is having an impact on people's lives broadly, even people who are not on these platforms. You did not need to be on Facebook in Myanmar to be dead. You just needed to be a Rohingya. You did not need to be on Facebook or YouTube in Christchurch, New Zealand, to be dead -- you just needed to be in one of those mosques. This stuff is affecting people who are not on these platforms, in ways we cannot recover from.

(Music)

(Music)

CA: I mean, I think everyone here would agree that the consequences of some of what's happened on social media are horrifying. People have died, people have been outraged, elections have been affected. It is horrifying. It's a threat to our future. But to me, it really matters how we talk about it to avoid igniting a situation where the people who could fix it won't, because they are so attacked -- that they feel unfairly attacked. So the question, for me, is not "Was it horrifying?" the question is, how much of it is unintended screw up, and how much of it is greed-motivated or some other motivated evil misintention? Because this really matters. Roger, there was a moment last year, for example, where, on the surface, Mark came out, there was a big apology, they changed policies, and as a result of the changes they made, they lost, what, over 100 billion dollars in market capital or something, in a single day, if I remember right? Meaningless? Was that any evidence of a desire to make a difference?

RM: I've been doing investing for 36 years, and Wall Street remains a mystery. Stock is back up to practically its high. So my one observation of greed versus unintended: I believe that the culture of the US economy very much favors monopolists and it really encourages monopoly. To the point where Peter Thiel wrote an essay in the Wall Street Journal, he's given speeches on "Monopoly is the right way to do things." And intellectually, I understand his point. It is, however, contrary to the basic ethos of the United States of America, where we associated monopoly with monarchy, and we associated small business and competition with the American way. And my point about this, Chris, is that I don't think it has to be either-or. Essentially, the "greed is good" mentality of Gordon Gekko has been the way businesses are run. We've abandoned the five stakeholders. The five stakeholders are shareholders, employees, the communities where employees lived, customers and suppliers. And now all we care about is the investors. And that makes it really short-term.

(Applause)

It basically means you sacrifice a lot of things that are in the public interest for the almighty buck. And you can just blame the shareholders for any bad thing you do. And my point is, I think that tech didn't create that, Silicon Valley didn't create that. But it is one of the exemplars of that problem run amok.

CA: But Mark is not really at the beck and call of investors. He's got majority control.

RM: He's one good night's sleep away from the epiphany where he wakes up and realizes he can do more good by fixing the business model of Facebook than he can with a thousand Chan Zuckerberg Initiatives.

(Applause)

CA: I think that's right. But I wonder -- I'm just speculating, but it's quite possible that in his mind, I'm not certain that becoming an ever bigger billionaire is the number one thing driving him. It might also just be he wants to continue to build something he views as incredibly cool, incredibly significant, and he's just doing it, in some ways, very wrong.

RM: I haven't known Mark really intimately in 10 years. So I don't want to pretend like I know. The thing I will say is that the Mark I knew was very idealistic. I think he viewed connecting the whole world as so obviously a good thing that it justified whatever took to get there. And I think that there's some things he missed along the way. Because if you look at it, you realize that his vision didn't have to go wrong, but it would have really helped if circuit breakers and containment strategies for emotional contagion had been built into the system. It would have really helped if he had maintained the religious adherence to authenticated identity, which was there at the beginning. The reason I fell in love with Facebook at the beginning was I was convinced that the fact that you used your school email address, that authenticated identity was going to keep trolls out. And that was going to make Facebook bigger than Google at that time. And the thing is, I think Mark thinks he's given the world a gift, and I wouldn't be at all shocked if he's just sitting there, wondering, "What the hell is everybody so unhappy about?" And I'm sitting there, going, "Mark, we're not unhappy about the gift, we're unhappy about these unintended consequences of what you did." And it's time to address those. And not by nitpickingly fixing the symptoms that showed up in 2016, but rather by going back and looking at the conditions of the business model that allowed that stuff to happen in the first place. I mean, why is it that we allow targeted voter-suppression ads in an election? Why do we allow companies to provide services to campaigns? There are all these things that you look at, you just go, hang on, just a sec, there are real problems with this model.

CA: I want to come on to those problems. But just spend a second just talking about the gift. Even now, there's a huge gift, you're talking about 2.3 billion users. There are a lot of people around the world whose internet experience is Facebook. I have met many people who have learned what they've learned on the internet via Facebook, and who, through Facebook, have been connected to a wide group of people from many countries who have transformed their lives. There's probably, literally, hundreds of millions of stories of human connection that worked out the right way, so let's put that on the table and not forget that that is there. And now come back to the crap.

(Laughs)

Talk about monopoly. Because the type of monopoly that these tech companies have is not the traditional type of monopoly. It's not that they are squeezing up the price of a product because they are the only ones who can supply that product. What type of monopoly is it?

RM: So here's the problem. Beginning in 1981, we changed our philosophy about antitrust, and we basically said the only measure of consumer harm we're going to look at any longer is price, increases in price. We're not going to worry about lessening of supply, we're not going to worry about terms and conditions, any of those kinds of things, pollution, anything. We're just going to look at increase in price. And the problem was, we see these products as free, but that's actually incorrect. What you really have here is a barter of data from the consumer for services. So if you want to understand if there's been a price increase, you have to look at the change in the value of data given up, relative to the change in value of services received. And there, it is demonstratively true that the value of data given up is growing much more rapidly than the value of the service being received. Each individual service doesn't change much. Gmail doesn't change that much, the blue app at Facebook didn't change that much, Messenger doesn't change that much. And yet, as a simple marker, the average revenue per user has been going up, very, very rapidly. And so, there is a whole project going on to bring antitrust to bear here, using that hypothesis. antitrust has been dormant, back to '94 in the Microsoft case, so I don't even know if we can get this thing in the first gear, but that whole discussion takes on weight, because these guys do behave monopolistically, as do people in almost every other sector of the economy.

CA: The basic argument is that when a company, a single company, get control of too much data, that that is dangerous for the country.

RM: If you're Snapchat, you have one data set. You're up against Facebook, which has at minimum seven or eight completely discreet data sets. Or think about Google. Search is one data set, email gives you identity. apps give you location, you have all these other data sets and when you put them together, the value goes up by more than a linear amount. And it creates all of these walls and moats that prevent competition, as well as creating network effects.

CA: And there's something hugely creepy and alarming about thinking of a single company knowing this about us, this about us, this about us, stuff that we don't even know, and then serving an ad that somehow exploits all these things that we don't know how they came to put that ad in front of us.

RM: How about something even creepier? Let's just do the Pokémon Go one here. You guys remember Google Glass, right, people going around, we called them glass-holes.

(Laughter)

We didn't like Pokémon, so they had to take it back. So they take it in the lab and they reformulate it in Google apps as a video game. Spin it out as Niantic, it's called Pokémon Go. They get a billion people going around with their smart phones and what are they doing? It's image recognition, it's following routes, going places. But it's also allowing for some really interesting experiments in behavioral manipulation. If we put a Pokémon in private property, will people knock on the door of a total stranger to get the Pokémon? Yeah, they will. How about if we put it in a place you've got to climb over a fence? Wow, they'll do that too. What if we put it in a Starbucks? Oh my God, they'll go into a Starbucks. How about if we put it in the third Starbucks, and give them 10 cents off, will they go to that one? Yeah, they will. The key thing to understand is, when you're in the world of behavioral prediction and behavioral manipulation, there becomes a divergence between your purpose and the purpose of the app. And the thing that we don't know and we have to have a conversation about is that these guys are really smart, there are no rules, we essentially allowed them to take control of massive data sets of unclaimed data. Google drives up and down the street, they call it Street View, and only the Germans push back. Then they do satellite view, then they do Google Glass, then Pokémon Go. Then they go and acquire all of our data, the banking data, the location data from cellular companies, health and wellness apps. They get all those data sets, they create the data avatar, and then they run experiments. Who's to stop them, who's to blame them?

CA: Roger, this is concerning, but I'm also --

(Laughter)

RM: Now we're all caught up, right? Now we're in the same place.

CA: I also think there's a conversation though, about language. You talk about behavior manipulation a lot, which is a creepy term and a stressful term, and you bring people out in the streets, which may be the right thing to do. But when someone put a Coke ad on TV 50 years ago, that was behavior manipulation, that's what advertising is. To me, the question is, I thing we have to be more careful about the language here, and try to separate genuinely creepy intent from reasonable use of data.

RM: Can I push back on that for just a sec? Because I'm not talking about intent, I'm talking about action. And what I'm saying here is let's concede that the intent was honorable throughout. Which I am prepared to do and have done throughout my activism. I'm simply saying that what winds up happening, because of the way the incentives of the business model work, you wind up getting creepy outcomes. If you are the person who thinks they're playing Pokémon Go and they're being tested as to what they'll do and what they won't do, it doesn't matter that the person had good intent. If you run over somebody by accident, kill them, you're not guilty of murder, you're guilty of manslaughter. And my point is, you can have unintended bad consequences for which you are still responsible. This is like chemical companies ...

(Applause)

We used to let chemical companies pour chromium and mercury into fresh water. One day we woke up and realized those externalities should be borne by the people who create them. That's all I'm talking about here. You know I'm not saying that they're bad people, I don't think for a minute they think of what they're doing as behavioral manipulation. But it doesn't matter, that is what it is.

CA: I think they would say it's behavioral manipulation -- that's what all advertizing is and always has been. The question is is it dangerous. Here's an example which everyone can agree is dangerous. If a company were to put together a clue from this behavior, and this behavior and this behavior, and decide, here is an addictive personality, therefore we will advertise them some painkiller, because we know they're going to go for it, and they'll buy it forever and we're going to get rich: evil.

RM: Right?

CA: But if the intention is, "You know what? If we could put together where someone is at this moment in time, with what we know about their preferences, we could give them an ad saying, you know what, 50 metres from you is a product that you've dreamed of your whole life. Why not stop the car now, pull over and get it?" Maybe that would actually be a positive contribution to someone's life.

RM: Hopefully, that's happening. Hopefully, in this thing, that the incentives have caused this to happen. I don't hear those stories getting told that much, but I'd love to believe they happen.

CA: Exactly, the stories aren't being told. The question is what then happens, because you're pressing hard for antitrust. Fundamentally, you think that several big companies should be broken up, like Facebook, Google, which of them?

RM: What I really want to do is I want to create space for alternative business models. I'm less focused on the break up model, than I am on, I don't think it's fair to have companies maintaining a market, and then favoring their own products inside the market. So Amazon, Google, Facebook all do that and historically, we have not allowed that as a country. I don't think that should be allowed. I'd like to look at this the way we looked at long-distance, where we went in from an antitrust point of view into AT&T and said, we're going to have competition long-distance, you have to provide lines to MCI and Sprint, and they're going to compete with you over your own network in order to introduce competition. You could do the same thing here, by setting an arbitrary limit so that a company who came in with a new business model got access to say, their first 10, 50 or 100 million users, over Google and Facebook, based on having a different business model. The same thing that happened with MCI and Sprint. That's where I go. I'm not focused on break up, because my view is if you don't change the business model, breaking them up is just going to cause the business model to proliferate. And what I'd rather see is a change in the business model accompanied by antitrust that allows for start-ups to happen. Because I believe fixing this problem created a bigger business opportunity than the business we have today. In tech, every single wave started with an antitrust case. AT&T in '56 creates computers, and it created Silicon Valley by taking the transistor and putting it in public domain. IBM in the '60s creates software and PCs, AT&T the second time creates cellular telephony and broadband, which is the internet, and then Microsoft, which creates Google and all that. I just want to follow that path, but I really, really, really want to change the business model.

CA: The tech companies might argue that if we are to allow technology to empower people to the max, they can't do that without knowing data. The more data it actually knows about someone, the more it can do for them, in principle. I'm wondering whether the solution to this is to allow consumers much more transparency to be able to control their own data: here I have a bank account, here is my data, it's blockchain-protected, whatever, I control it, I can license it to companies, companies have to tell me which of that data they're using, which they are adding to or whatever, but I control it. Isn't that a way around this?

RM: Absolutely. But here's where I would start. The problem we have today is if you start from the status quo, you're negotiating down from 100 and you wind up at the [General] Data Protection Regulation, which only addresses the data you put into the system. It doesn't touch the metadata about what you're doing, it doesn't touch your browser history and it doesn't touch all the third-party data that's available to be bought. So your banking data, your health data, your location data and all that. And so I would rather zero-base what we're doing, and then have the negotiation from there about what should be allowed. And again, I'm an activist, so I'm taking the pure form, just as they are taking the pure form from their point of view now, and I want to have the debate and we'll come down somewhere in the middle. I am not an absolutist on any of this, but I think if we don't at least actively consider what it would look like to eliminate all of -- Why is it possible to follow people around the web? Let's think about Google and Gmail. They tell you they're a platform, not a media company, they're a common carrier. But they're reading your emails for their economic benefit. If they were at the postal service or FedEx, they'd go to jail for that. We've never had a conversation about what uses of data are legitimate and which ones are not. The health data -- HIPAA is not perfect, but doctors' can't sell your menstrual cycle, right? Yet, that is what happens today. My own point is, we need to understand, we all have to get everybody up to speed on what's going on, and then have the debate. And maybe I don't win, and I'm cool with that.

CA: Roger, you've done an amazing job of highlighting a huge number of issues, it's taken courage to do it, you've risked losing friendships you've had in Silicon Valley. It's really remarkable. I don't know of a similar story of someone who's done such a U-turn and come out so passionately and eloquently. So I definitely want to recognize that.

(Applause)

I think it would be exciting, with this group, to by all means have a crisp question for Roger, but also, let's think about the way forward.

(Applause)

Carole Cadwalladr: Thank you, Roger. It's so powerful, your voice on this subject.

RM: So this is Carole Cadwalladr, who is my hero.

(Applause)

Nobody was listening until Carole showed up.

CA: For the people listening on the podcast, Carole gave the opening talk at TED and absolutely ignited the room. There was a massive standing ovation -- it was electrifying, Carole.

CC: So, Chris, I really hear what you're saying about good intentions gone wrong. We can buy that. But it has to be followed up with action now. And so, I spoke in my talk about the case of Brexit being the petri dish for Trump. And I've been agitating in Britain for a public inquiry, but it's not going to happen, because our government is complicit in many of these crimes. The thing I was thinking about in the last day was about some sort of people's truth inquiry, trying to gather in all of the data, and doing CSI Brexit, essentially. A kind of forensic examination. And I would say again, if Facebook, if they have turned the corner, if they want to be well-intentioned -- Facebook, hand over that data. Let us see it.

(Applause)

RM: First of all, thank you for the question, because I think we actually do need to do the study you're talking about. There are two different things going on. We need to understand what the failure modes are, and we need to help the companies get to a place where it's safe for them to open up, to share everything that they know, everything that they've learned. Because at the end of the day, what I would be in favor of would be giving them an amnesty in order to open up all the books. Let us see everything that was done.

Woman: Hi. I would urge you not to seek amnesty. I feel that would put us right back in what you very eloquently said was the problem, with say, the Goldman Sachs bailout. Or that there is never any consequences for terrible behavior, and if Facebook, or all the tech companies get amnesty, then there will still be no belief, there will be no consequences for people doing something wrong. And it would just tell a generation of more tech people that, look how many billions of dollars you can make and just get away with it.

(Applause)

CA: Thank you. We're going to go here, you have a story to tell. Right here.

RM: Wait a minute, this is Christopher Wylie.

Christopher Wylie: Hi, can people hear me? Is this on?

CA: It's very cool to have you here, Christopher.

(Applause)

RM: I didn't recognize him because his hair is not pink.

CW: My name is Christopher Wylie, I'm the Cambridge Analytica whistle blower.

(Applause)

Fantastic talk, Carole, by the way. So, I've been talking with a lot of members of Congress. My concern about -- we call them filter bubbles or segmentation. For me, I worry that what is happening on Facebook and more broadly, on the internet, is actually a new form of segregation. When you think about the impact, why it matters for us to be able to sit in the same space and have the same common experiences so that we can be citizens together.

(Applause)

CA: Thank you.

Paul van Zyl: My name is Paul van Zyl and I previously served as the executive secretary of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and therefore resonate very strongly with Carole's points about, there needs to be some form of truth. What we did at the Truth Commission is, we tried to establish who did what to whom, and create an official record that would stand the test of time and be handed down from generation to generation. And I think the trick here is, we still don't yet have an official reckoning when it comes to Brexit and when it comes to the US election, and many more elections, I would add, about who did what to whom on the platform of Facebook. And I think that what we need to do is create a record which says it is no longer permissible to spread the lie that Facebook hasn't been used as a platform that has demonstrably affected the results of elections. And once we establish that as a fact, then let the remedies begin.

(Applause)

CA: Thank you.

Woman 2: Hey Roger, you're someone who's benefited from the platform, you have a lot of friends in Silicon Valley or people that you know, you're highly influential, yet we see this happening over the last couple of years, and you've written a book. What else have you done, have you gone to Washington, are you bringing a think tank together, what more can you do particularly?

RM: I go to Washington every single month. The book tells the story of all of that -- going there in the summer of 2017, building a coalition, Tristan effectively triggering the hearings that happened, us training the committees to do the hearings, working with the Federal Trade Commission, working with the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department. We're doing our best, but there's a very small number of us. And we're looking for volunteers, and if you'd like to volunteer -- My basic point is, don't look at me as the gating item here. There's so much to be done here and so many smart people do the thing that you can do.

CA: But the significant part of the tech briefing of many members of Congress and the Senate came from your group.

RM: Well, Renée DiResta did most of it. And the thing I will just to you is, until the fall of 2017, Congress knew, as certainly as it knew the sun would come up tomorrow, that it didn't need to worry about tech. So we're catching up.

Samantha Esson: Hi, my name's Samantha Esson. I just wanted to touch on two things that I heard that I think are really important to digest. One, Chris, you actually said it, which was this concept of us selling back our data or licensing it out, and I think what's really critical is we understand there would be a huge disenfranchised group of people who would have no idea what that truly means. And that's part of the reason why, right now, they're openly just giving away their data to these companies for the use of a game or any of those types of things. So I want to keep that in mind. Second, I want to circle back to this concept that humans are innately good, because history tells us sometimes they're not, right? And this concept of greed. So you talk about, would they, if they could, you know, it wouldn't hurt their business model, trade doing business as, so that they can really dig in to the good, and I'm going to say I don't know. Because I think there is so much greed in our society, and perhaps some of the behavioral things we need to study is why do we allow greed to drive us.

RM: And power.

CA: You know, when you start thinking about data and analyzing it this way, it actually becomes that there are paradoxes in this. So if you think about Facebook as a 55-billion dollar revenues company, there's about 2.4 billion regular users, basically, the company's getting about 20-25 dollars per user per year from advertisers. But that is massively tilted towards the US. In the US, they're getting more, like 100 dollars, I want to say, in ad revenue per user. Much of the rest of the world, they're getting almost nothing. One way, if you wanted to put it this way, the current structure is the rich subsidizing a service for the poor. The data of the poor is not worth that much -- they're getting connection or whatever for much less money than those of us who are being served expensive ads to buy houses or whatever. And so in trying to imagine a different model for Facebook, it's really hard, right?

RM: Really hard.

CA: Last year, Jaron Lanier said the problem is we're trying to give this stuff for free -- we should be selling a service. If you were to sell a service, it's not clear that you could ever make that business model work, because in the US, you'd have to charge over 100 dollars per person, which would mean a lot of people wouldn't sign up, you'd have to charge a lot more, there might not be a business there.

RM: If we don't fix these problems, that's a risk we may be forced to run. Because the thing we have to get prepared for is that governments are getting really unhappy with the bad stuff that's going on. New Zealand looks at this stuff, the UK is thinking about much more onerous stuff. It's not crazy to imagine a country shutting down services the next time something goes wrong, to keep things from spreading virally. And I just think it's incumbent on the industry to get into the game and recognize that the business model as it's currently being practiced is not sustainable.

CA: I think Bill Joy has a question.

Bill Joy: When information is so powerful that it's a weapon, then we have to think about regulating information. So we're facing that with these companies. Now it's distasteful to regulate the information in a way that's offensive to our belief in free speech. But what we've done for far too long is exempted the technology industry from liability. In the days of software, they didn't have to --

(Applause)

Congress passed a law, they were exempt from general merchantability warranty of fitness of the software. Microsoft couldn't be sued for consequential damages of any kind, for flaws in their software. So it seems to me that the kind of exemption we've given these guys, is that they can publish whatever they want, and they don't take any responsibility, when they're clearly a publisher, as much as a newspaper is a publisher, is unacceptable. You could say that won't solve this general problem we've been talking about, but I think that's not true. Because if they were forced to behave in a way that they had what lawyers would call strict liability for certain of the things they published, that would force their business models to be renovated in a way that would fix many of these other problems as a side effect. I'll take a single example, this issue of the Sandy Hook parents and Facebook. They were publishing things which drove the Sandy Hook parents into hiding. If a newspaper had done that, they would be out of business. And they've got an exemption from liability for that, which should be removed.

(Applause)

Abiola Oke: My name's Abiola. I find the conversation actually quite ironic and interesting, because as an African, foreign entities have been meddling in the political autonomy of African sovereign nations for so long. So it's actually quite ironic for the first time to see Western entities deal with their own creation and how it's meddling with their own --

(Applause)

I mean, long before cobalt was found in Congo, this has been going on. So, I guess my question to you is how can we think differently about the capitalistic framework. Can investors start to incentivize or behaviorally manipulate us to support and give our data to companies that incentivize us you know, either from a data tax of some sort, and support companies that are doing the right thing so to speak, with our data, not manipulating us.

RM: So really simply put, let's remember that capitalism requires someone, historically the government, to set rules and apply enforcement equally across the whole population. We currently do not have that in the United States of America. So reinstating that would be great. And then I think changing the values system back to the old model of recognizing that every business has at least five constituencies. Shareholders, employees, the communities where they live -- which might even be viewed as the whole country and the world -- suppliers and customers. I think changing that philosophy would really help. But I do think this is about a broken culture of what used to be called capitalism, that is now something else. But your point about colonialism, that's exactly how I see it.

CA: So I think the instinct of pretty much everyone who comes to TED is as a problem solver. You, Roger, have highlighted in the most graphic way some really, truly, deeply intense problems that we're facing now. And I just am full of dread, but I also hope that people are out there, working to solve these problems. And I would like to wrap this up by telling us what is your prognosis. Do you think we can build a way out of this, regulate a way out of this, a combination of all the above?

RM: I'm actually incredibly optimistic. In the past year, in the United States, I think we've had five teacher labor actions that worked with no blowback. The air traffic controllers with that partial sick-out ended the government shut-down. McDonald's has abandoned their fight against the 15 dollar minimum wage. Elizabeth Warren introduced an antitrust policy that a bunch of republicans said to me, "I can't believe we let a Democrat beat us to the punch on this idea." Because it was Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft's basic approach. I'm going out there and what I find is that everybody I meet, whether they're on Fox or MSNBC, whether on Fox Business or CNBC, whether they're on conservative talk radio or NPR, everybody sits there and goes, "I get it, there's something wrong and we all have a role to play in this."

And the thing is, we don't have to give up the products we love. Because these businesses are not going to go away if they do what I want them to do. I mean, there are so many pieces of Facebook that are unmonetized that could be monetized without hurting anybody -- this is nuts. This is about a power argument. Can they do it their way, or do they have to actually sit at a table and talk to us about the right thing to do?

I believe that Mark and Sheryl, Larry and Sergei, and everybody else who is involved in this, is capable of getting this thing right. And I want to see a truth commission, I want to see an end to digital colonialism. I want to see everybody benefiting from the next wave of technology. I want to see the next big thing. But first, we've got to get together and say it isn't about Left or Right, it's about right and wrong.

(Applause)

CA: Well said.

(Applause)

Mark Zuckerberg or Sheryl Sandberg, if you're listening, if you want to have a conversation, I'm here, ready to listen. Roger McNamee and the TED community have gathered here. Thank you for coming and taking part in what is probably the most important conversation of this moment.

RM: Thank you.

(Applause)

(Music)

OK, that's a wrap for this episode. Do consider sharing it with anyone you know who wants to dig deeper into ideas. Please consider rating and reviewing The TED Interview on Apple iTunes or wherever you listen to podcasts.

This show was produced by Michelle Quint and edited by Sharon Meshihi. Our production manager is Roxanne Hai Lash, our mix engineer David Herman and our theme music is by Alison Leyton-Brown. Thanks so much for listening, see you again soon.