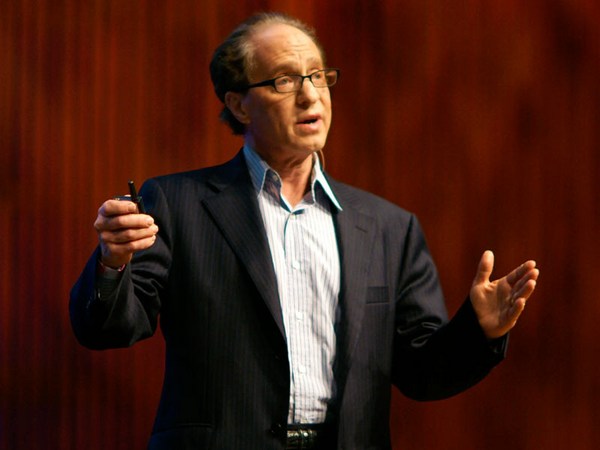

Chris Anderson: Welcome to the TED Interview. I'm Chris Anderson, and this is the podcast series where I sit down with a TED speaker and we get to dive much deeper into their ideas than was possible during their TED Talk. Today's episode was recorded live at the TED conference. It's a conversation with inventor and computer scientist Ray Kurzweil. Ray is probably best known for articulating the idea that technological change is accelerating relentlessly. It has been for years, and it's going to continue to accelerate, culminating in this event in the not too distant future, called the Singularity, when computers are suddenly so much more intelligent than humans, that all bets are off; change happens at an unimaginable pace. Now, this belief which Ray has set out in a series of compelling books, has encouraged him to make a spectacular series of predictions about the future. When I spoke to Ray at TED, I asked him about his vision of the future. Here's our conversation.

(Recording) Welcome to the TED stage, Ray Kurzweil.

(Applause)

Ray, let's start with what I think is the underpinning idea of so much of your work, which is the idea that technology is fundamentally accelerating. Explain that.

Ray Kurzweil: So, around 1981, I wanted to tie my inventions. The inventors whose names you recognize, like Thomas Edison or Larry Page, were in the right place with the right idea at the right time. So I started studying technology trends. I didn't think I'd find anything overly predictable. I started with the common wisdom, 'You cannot predict the future," and I made a very surprising discovery, which is: anything having to do with information follows a perfectly predictable trajectory, and that trajectory is exponential. And our intuition about the future is not exponential, it's linear. The primary difference between myself and my critics is, we're looking at the same world, and they just use their linear intuition, it's just obvious.

Halfway through the genome project, one percent had been collected, so mainstream critics said, "Oh, one percent, seven years, it can take 700 years, just like we said originally." I said, "Oh, one percent, we're almost done," because one percent to only seven doublings, it had been doubling every year, and indeed, it was finished seven years later. That's continued since the end of the genome project. So that's the essence of the idea, and it really is the foundation of my futurism. I did it primarily to tie my own technology projects. And that continues to be the primary goal. But it also enables me to invent with the technologies of the future, because I don't have the computers of 20 years from now, but I can write about what the impact will be.

Chris Anderson: What is it about the modern world that has driven that exponential increase? Why does that happen?

RK: Well, that's a very good question. I don't think we fully understand that. For one thing, it's human nature to try to increase things multiplicatively. If we're at one, we try to make it two. If we're at a 1,000, we don't try to make it 1,001, we try to make it 2,000. And we create the computers of next year with the computers of this year. So our tools are getting exponentially better, and that enables us to keep that exponential going. People say that exponentials can't go on forever, and that's true and there are limits, but they're not very limiting. I mean, we'll be able to multiply human intelligence trillions-fold before we run out of capacity.

CA: So this way of thinking allowed you -- for example, in your book, "The Age of Spiritual Machines," you made a large number of predictions about the future that surprised people at the time.

RK: A hundred and forty-seven.

CA: A hundred and forty-seven? So what percentage of those actually came out?

RK: You can Google how my predictions are faring, and it analyzes those 147 predictions. Eighty-six percent were correct to within one year. Some of the ones that were wrong, the 14 percent, were predictions like we'd have self-driving cars, which is off by maybe five years, so they were still directionally correct.

CA: Give us a couple of examples of the ones that you got right at least 10 years before they happened.

RK: I actually wrote them in the mid-1990s, so I thought you might ask that.

(Laughter)

So I'll just quickly -- That the law of accelerating returns would continue for all these different information technologies -- computation, communication, genetic sequencing. People would predominantly use mobile computing. A lot of these seem obvious because it's happened, but it was not obvious in the 1990s. Computers would have no moving parts, disk drives would become obsolete. Books, music, movies would become data files, distributed through wireless networks and not physical objects. Computers would routinely have wireless internet connection, be able to identify their owners from their faces, chips would go from 2-D to 3-D. Computers would play an essential role in every facet of education. Majority of reading is done on displays.

CA: You're now telling us today's news headlines and so forth. I mean, this is an amazing track record, I think. But of course, we now have to ask you politely to make a new prediction for at least 10 years out that you've not made before. Because this is TED.

(Laughter)

RK: Yeah, that's challenging, because I've made a lot of predictions. So, a trend that's happening -- I mean, I've been writing since the 1980s on how things are getting better. That's going to accelerate. I had an onstage dialogue with Christine Lagarde at her annual IMF meeting, and she said, "Well, yes, there's all those fantastic things in digital technology, but you can't eat information technology, you can't wear it, you can't live in it." And I said, "All that's going to change. We're going to have 3-D printing printing out clothing, starting around 2020. We'll print out modules we can snap together and create a house. That was demonstrated recently in Asia. We'll grow food with vertical agriculture, hydroponic plants for fruits and vegetables, in vitro cloning of muscle tissue for meat. Basically, making these physical products into information technology. And we'll have a 50 percent deflation rate, because you can get the same computation you could get a year ago for half the price, so 50 percent deflation rate, and that will attend these nominally physical products.

A prediction -- I would say that in the early 2030s, we will have UBI, universal basic income, in the developed world. It will be worldwide by the end of the 2030s, and you'll be able to live very well on that. When we talk about jobs going away, people are alarmed by that, because they are dependent on jobs for their basic material needs of life, but the primary concern will be on meaning and purpose. So we have UBI now in kind of a disorganized way -- food stamps, housing assistance, Medicare, Medicaid. I befriended a young woman who was homeless and panhandling in front of Whole Foods. So I said, "You should contact you sister," because it became apparent that she had a sister. And she said, "Well, I don't have a phone." "I'll get you a phone." And she says, "You sound just like my therapist."

(Laughter)

So she actually has a therapist provided by San Francisco. Now, maybe not every city does that, but ... So we have kind of a disorganized form of UBI today, that will become, I think, standardized by the 2030s. And you'll be able to live very well on that. And we'll still compete for attention, to give a TED Talk, to publish a book and express yourself ... The competition really will be for purpose, as we move up Maslow's hierarchy.

CA: OK, so I want us to note this down correctly, because this actually was a bold prediction. So if I heard you right, correct me if I'm wrong, you're saying that by the early 1930s, Western countries will --

RK: Twenty thirties. CA: Sorry?

RK: Twenty thirties.

CA: Damn! I'm always 100 years late for everything.

RK: Well, we did put social security in in the 1930s.

CA: It's a lot easier to make predictions of the past. By the early 2030s, Western countries -- or richer countries, shall we say -- will be rolling out UBIs, universal basic income, enough for all of their citizens to live comfortably. And by the end of the 2030s, that will be worldwide. ... said Ray Kurzweil, at TED, in 2018.

RK: You'll have to invite me back, and we can discuss whether or not it happened.

CA: OK, so that's really interesting. I think six years ago, you took a job at Google, with a mission to use artificial intelligence to understand, to work on the semantics of the web, of knowledge, generally.

RK: Right, so there's a connection to TED on that, because I came here and talked about my book "How to Create a Mind," and I articulated a thesis I had actually been thinking about for decades. And it's different from a big neural net. There's actually no back propagation in the human brain, so it works differently than these massively parallel neural nets. It's actually many modules, each of which can recognize a pattern. And they're organized in a hierarchy, and we create that hierarchy with our own thinking. I talked about that here at TED --

CA: Wait -- that's your vision, or that's what's in the human mind? That's what's in the human brain?

RK: That's how the human brain works, and that's a good model for how to create AI. So I'd given an early version of that to Larry Page, he liked it. I met with him, asked him for investment in a company I'd started to develop those ideas. That's how I went about things as a serial entrepreneur. And he said, "We'll invest, but let me give you a better idea: Why don't you do it here at Google? We've got all these great resources. You know, life begins at a billion examples in deep learning. We have a billion examples of some things, like pictures of dogs and cats, we have lots of computers, we have a lot of talent." And so, we struck a deal, and I took my first job for a company I didn't start myself, a few months later. And the mission, and what Larry asked me to do, was to create semantic search -- search by meaning, rather than keywords -- and ultimately influence search to move in that direction. So I have a team that's about 40 people, and we have created semantic search. Our first application was Smart Reply. Our technology plays a role in the Google Assistant, Google Home, and we're working with other teams to move towards actually understanding the meaning of language.

CA: And so what does it mean for a computer to understand, you know, to look at a paragraph of written text there and understand it?

RK: Well, it has to have some way of modeling the intent and what the different elements are, that it's referring to different things and understand going to a conference, and what is a conference, it's a gathering of many people where they share ideas, it's called TED, do we know something about TED, and be able to actually build up meaning from language. So we don't do it quite at human levels, but that's going to come by 2029. That's been my consistent prediction. On the other hand, it can read much more quickly than humans. So, a good example is this product that's called "Talk to Books." You ask a question, and the software then reads 120,000 books in a half a second, which is pretty fast, I mean --

(Laughter)

it takes me hours to read 100,000 books.

(Laughter)

We had it read a million books and it took six seconds, and people said, "People are never going to wait six seconds."

(Laughter)

It understands the meaning of the question, and it understands the meaning of the sentences, the six-hundred million sentences that it reads. And it gives you the best examples it can find that answer the question, based on semantics, not keywords.

CA: It sounds like it knows what mammals are. It knows that cat is a mammal, it knows that mammal is an animal -- this type of thing that builds up pieces of our common sense.

RK: It has a vast connection of the links between these different concepts and how they relate. Not quite at human levels, but an implication is that once it achieves truly human levels, it'll have that in every field, whereas humans tend to be experts in one thing or another. And it'll be able to read a billion sentences in a second and really understand them. And then really read everything on the web. I've heard that not everything on the web is accurate, but we have an ability to assess, based on what other people say about different sources, and asses the credibility. So it really will be able to become a master of all knowledge. That's the implication, that's 11 years away.

CA: The implication of what you're saying is, there actually is no moment when we have human-level intelligence, because the moment that we do, we have a being with human-level intelligence, but with the whole world of human knowledge. And that feels like that brings with it superpowers.

RK: So we've seen an example of how quickly computers go from kind of average adult ability to superhuman abilities in a particular area. There was a discussion here about AlphaGo. There's a motto in the field that life begins at a billion examples, as I mentioned earlier. So the DeepMind folks had a 100-layer neural net study every online move of masters in Go. It's not a billion, it's a million. And it created an, I'd say average, adult amateur player. They were able to then generate a billion moves by having it play itself. And then they had AlphaZero, which dispensed with the million human moves and just trained itself starting from completely random play, and within hours, actually, was able to defeat AlphaGo, which had defeated the best human player, and do the same thing in chess.

Once a computer achieves human adult levels, it very quickly soars past it and becomes superhuman in that area. Once that area is basically all of human ability, it will be able to do the same thing there. A good example is driving a car. That's very, very complicated. It's in the real world, there's all kinds of vagaries of things that might happen. So the strategy that Waymo, the Alphabet subsidiary, is using, is they developed software, they tuned it by hand, they had it drive with humans at the wheel to take over, three and a half million miles. And that was enough to create a simulator of the whole world of driving. And now they've driven simulated cars a billion miles in the simulator. And so it's able to actually do the same thing that AlphaZero did, by basically kind of playing itself with a very good simulation of the world of driving.

CA: But this is so stunning, this development, in the last couple of years. Everyone who I've spoken to in the field was so stunned by the AlphaZero achievement, especially in chess, the fact that you could create an architecture that only knew the rules of chess -- no databases of opening moves, no actual games, let it rip, let it play and learn and figure it out. And within a matter of hours, it not only beat every human player, it had wiped out 30 years of attempts to program chess computers. I mean, that's an incredible thing. It's kind of a terrifying thing in its own way, because, I mean -- apply that to language, Ray. You know, you're building technology here that is already starting to put concepts of a world together. It's like, "This is how to think of the world, and this is how words react to those concepts." Isn't there an AlphaZero-like machine that can say, "OK, thanks for the starting point, now just give me all the world's knowledge," and actually, suddenly, we wake up on a Tuesday, and this thing has encyclopedic knowledge, and can actually engage in commonsense language.

RK: But the strategy I just described, of simulating moves and countermoves in a simulated environment, doesn't really work in this case, because language -- I mean, Turing's insight in basing the Turing test on language is that language embodies all of human intelligence, and there's no simple methods or tricks where you can have a shortcut. So we're painstakingly building up the ability to understand language, but there's no simple way to have it kind of play itself and within hours, ramp up its knowledge.

CA: ??? ___ right now. So the Turing test, that's the moment when a smart panel of judges can engage with a computer and not be able to tell that it's a computer rather than a human, despite minutes and minutes of interrogation.

RK: Exactly. Turing described it as teletype communication -- basically, text messaging. There's been proposals, "Well, let's actually have a visual presence and spoken ... Actually I don't think that makes the test any more difficult. We already have synthetic speech that's very convincingly human. And we can create visual avatars -- we're almost there -- that are very human. It's the language, understanding the language that is the heart of the problem. And Turing was very prescient in defining language mastery as requiring the full depth of human intelligence. There was a recent milestone, to put this in perspective.

When I came to Google, the state of the art in computers taking these paragraph comprehension tests, where you read a paragraph and then answer questions, was, the computers could ace the second-grade test. Third grade, it didn't do so well, because it didn't really understand that if a kid has muddy shoes, she probably got that by being outside in the mud, and that the mud is going to get on the kitchen floor, and moms and dads don't like muddy kitchen floors. That's what we call real-world knowledge, and it just didn't have a clue. Just a few weeks ago, two different computer systems using deep neural nets got slightly better than average adult performance on the adult test. So that's a pretty startling milestone. Where it breaks down is what we call "multichain reasoning," where to answer a question, you have to kind of understand the implications of this part of the paragraph and this part and this part, plus some real-world knowledge that's not even stated in the paragraph. It kind of falters on that. We have ideas on how to do that.

CA: And in your worldview, is it from that moment that we are basically at the Singularity? From that moment, it's -- foof! -- we're off.

RK: The Singularity I have is a somewhat different concept, although this is a precursor to it. The 2030s, we will merge with the intelligent technology we're creating. So I mentioned, two million years ago, we got this additional neocortex, and we put it at the top of the hierarchy. And that enabled us to invent language and technology and conferences, something that no other species does, combined with another evolutionary innovation, which is the opposable appendage, where we could actually manipulate the environment and create technology. So a lot of the discussion here about AI talks about it as if it's a new species and how we're going to interact with it, and will it be kind to us, and we have to give it our values. My view is, we're going to do with that technology what we have done with every other technology, which is extend our own reach and make ourselves more capable. Who here could build this building? So we have machines that leverage our muscles and enable us to create skyscrapers. A kid in Africa can access all of human knowledge with a few keystrokes. And while it's not yet inside our bodies and brains, it may as well be, because we don't dare leave home without it. It really is an extension of our minds.

So we're going to create synthetic neocortex in the cloud. We're beginning to do that. I mean, 2030s -- we'll have very accurate simulations of the neocortex. And just as your phone makes itself a million times more capable by connecting to the cloud, we will connect the top layers of our neocortex to synthetic neocortex in the cloud. And just like two million years ago, we will put that additional neocortex at the top of the neocortical hierarchy. Only this time, it won't be a one-shot deal. Two million years ago, if our skulls kept expanding, birth would have become impossible. But the power of the cloud is not limited by a fixed enclosure, it's doubling in power every year now as we speak. So we will have an indefinite expansion of our neocortex. And just like two million years ago, we will create new forms of expression that we can't even imagine today. Try explaining music or language to a primate that doesn't have enough neocortical capacity to understand it. You could try explain that for years, it just doesn't have the capacity. So we will create new forms of expression, new forms of music, that will be as profound as what we do today is, compared to what primates can understand. So that's the implication. If you then do the math, we will expand our intelligence a billionfold by 2045. That's such a profound transformation, that we borrow this metaphor from physics and call it a singularity.

CA: Twenty forty-five. And so, the point at which we'll be able to expand our frontal cortex, at that point, in a sense, even if other parts of our bodies start to suffer and go, it's possible to imagine that our consciousness lives on and actually gains in creativity and power and ability to do other human things, right?

RK: Over time, the nonbiological portion of our thinking will become more predominant. In fact, it will become powerful enough to fully understand and model and simulate and recreate the biological portion. But a whole other theme is, we're going to have more and more powerful technology to keep our physical bodies going, and we'll be able to express ourselves with more than one body. People will think it pretty primitive that, "Wow, back in 2018, people only had one body and no backup, and they couldn't back up their mind file."

(Laughter)

CA: So Ray, I want to ask you a personal question. We didn't talk about this, so tell me to shut up. First of all, how old are you now, today?

RK: Well, I had my 70th birthday a few weeks ago. No, wait -- did I say 70? I meant 30, I'm sorry.

(Laughter)

CA: So you're here at 70. And on your timetable, Turing test is passed in 11 years' time. Soon after that, there's capabilities to really be empowered by these new digital technologies. Do you feel yourself to be in a race against time, that there's a real chance that the Ray Kurzweil being, and you, will transform and live on in another form?

RK: Well, there's a whole other theme, which is radical life extension. And I've written three health books, the last two, coauthored with Terry Grossman, MD, and we talk about three bridges to radical life extension. Bridge one is what you can do now, that's a moving frontier. Bridge two -- and there's been a lot of discussion here -- is biotechnology, basically, reprogramming the genetic processes, which are information processes of life, to overcome disease and aging processes. So for example, reprogramming the immune system, which, ordinarily on its own, does not go after cancer. To do that is called immunotherapy. That's a very bright light in cancer treatment. That's an example of biotechnology. So what we're headed towards is a concept called "longevity escape velocity," where you're adding more time than is going by, not just to infant life expectancy, but to your remaining life expectancy. I believe that will happen for diligent people in the developed world in about a decade. I actually feel I'm there. Now, the fact that your life expectancy is a certain, whatever it's computed to be, and the definition of it is tricky, you could still be hit by the proverbial bus tomorrow. We're working on that also with self-driving vehicles.

(Laughter)

On aging tests and on various other kinds of measures, I'm holding my own, and I would say I've personally achieved longevity escape velocity. It's never a guarantee; you get some disease out of the blue ... But the ones I track, I'm doing very well. So that's the goal, to keep this biological body going until we have means of, as you were alluding to, being able to back ourselves up and so on.

CA: I would like to give this audience a chance to ask questions. We've got these mics that you can throw. Let's start here.

Man 1: So, Ray, one thing about when you start uploading stuff into the cloud and the synthetic neocortex. At this point in time, affluent people still have to educate their kids. But here there is a possibility that they could just afford a larger, more powerful neocortex in the cloud, and then the inequality would become even worse, because then what would happen is, if you have money, then you could actually afford superior intelligence than people who don't have it.

RK: Well, one objection I get is, "Oh, only the wealthy are going to be able to afford these technologies that Kurzweil talks about." So one answer I have is yeah, it's like smartphones, where you had to be wealthy to have a portable phone. And it kind of didn't fit into your pocket, it was a big object. And it did one thing: make phone calls poorly. Now we have devices that do a million things, and there's three billion of them. And there will be six billion in a couple of years. So these technologies are only affordable by the wealthy at a point in time where they don't work.

(Laughter)

By the time they work fairly well, lots of people have them, and by the time they're really perfected, they are ubiquitous and almost free. People who have smartphones today, they're not limited by the capacity they have, there's kind of unlimited capacity for what you need to do in the cloud.

CA: Here we go.

Man 2: Hi. In radical life extension or agelessness in other ways, how is the role of nutrition and food going to change? I mean, do you take a lot of pills, are you going to eat regular food?

CA: You take a lot of pills, rumor has it.

RK: Well, it's down. When I wrote "Fantastic Voyage," which was 2005, I was taking 250 a day. It's down to 100, so a much more efficient program. And so far, so good. But that's all part of bridge one. Bridge two will have much more powerful ways of reprogramming the information processes of life. And it is an information process. Bridge three, the quintessential application will be medical nanorobots, it's an application of nanotechnology, which will go inside our body, extend the immune system. The immune system evolved when it was not in the interest of us to live very long. And basically, there are scenarios to wipe out every disease and aging process with these medical nanorobots. I used to call it the killer app of nanotechnology, but that was not a good name for a health technology.

(Laughter)

Woman: Hi, Ray. At the end of "How to Create a Mind," you talk about the way that you interpret sentience. I was wondering if you could explain to us all how you think we should be thinking about AI in terms of sentient beings and how that would change as they become more lifelike?

RK: Well, consciousness is not a scientific issue. There's no machine you could build that you slide an entity in, and OK, the green light goes on, this one's conscious, this one isn't. So some scientists would say, "Well, it's not scientific," which is true, "So let's not waste time on it, it's just an illusion." That's not my view, because our whole moral system and ethical system and loosely, our legal system, is based on consciousness. If you hurt or extinguish the consciousness of a conscious person, that's a high crime. If I destroy my property, provided it's not conscious, that's OK. If I destroy your property, it's probably not OK, but not because I'm causing pain and suffering to your property, but to you, the owner of it. So we do need to determine who and what is conscious. Now, we have a shared human assumption that other humans are conscious, at least ones that appear to be conscious, but we disagree if we go outside shared human experience, that's what the whole debate about animal rights is: Are animals conscious and which animals, and what are they conscious of? We will have that debate about AIs. My view in connecting this to the Turing test is: if an AI passes a valid Turing test -- with emphasis on the word "valid," meaning, it really is convincing that it's having subjective experiences, that when it claims to have a subjective experience, it has the subtle cues that we associate with that subjective experience -- my leap of faith is that AI will be conscious. And I also believe that -- this is an objective prediction -- that the majority of people will agree with that, because we'll want to accept the consciousness of these AIs. They'll be very smart, and they'll get mad at us if we don't think they're conscious.

CA: This is such an important discussion. I know that Max Tegmark might have a different view. Yuval Harari has a different view, that people will actually distinguish between intelligence and sentience. And it's perfectly possible to imagine a world where intelligence vastly increases or surpasses human intelligence. But because we know how these things are made, and there's a direct pathway back to a calculator, that they won't believe that they are sentients.

RK: Yeah, but there's a path back to a calculator from the human brain, too.

CA: It'll be a debate, I'm not saying it's right. This is a really important debate, because --

RK: That's kind of a model where there's the AIs, and there's the humans, it's all going to be mixed up. We are going to become predominantly AIs by extending our thinking through AI in the cloud.

CA: But isn't it possible that a key way of keeping AI safe is to build in a principle, you know, don't hurt the things that can love and feel and feel joy? And that in that scenario, it's really going to matter whether we think they can love and feel joy, because if they can, then we quickly get sidelined, because they'll be able to amplify their love and joy much more quickly than --

RK: Well, that is our rule in human society. Being able to love and care -- it's a description of consciousness. And our moral system forbids causing pain and suffering or extinguishing the experience of conscious entities. A lot of the discussion I've heard this week is, "OK, how are we going to relate to the AIs?" And the AIs are over here, and humans are here. We're already very mixed up. We don't leave our homes without our AIs even today. And they'll be much more intimately integrated with us as we go forward.

CA: It sounds like you believe: Turing test passed in 2029. Right after that, we will suddenly have a whole new basket of moral obligations not to cause pain to that evidently conscious new thing that we have created. That's a huge revolution right there, of course.

RK: Yeah, I'll have to think about that one.

CA: Alright, Max.

Max Tegmark: So, I'm curious, Ray. As you sit here and look out over all these researchers and entrepreneurs and thinkers, so many of whom are working to improve our technology, if you feel that there's any one thing you would like to call out that we as a community are not working hard enough on, and if so, what is your Kurzweil challenge to us, to make sure that this future envisioning becomes inspiring?

RK: The biggest challenge facing humanity is promise versus peril and reaping one while we control the other. My generation was the first to confront an existential, technological risk to all of humanity. I remember the civil defense drills we had in elementary school. We'd get under our desks and put our hand behind our head to protect us from a thermonuclear war. And it worked, we made it through.

(Laughter)

And we have other existential risks emerging -- biotech, AI ... I mean, we've seen lots of scenarios in dystopian futurist movies. I think they're unrealistic, because it's always the AI versus a brave band of humans for control of humanity, and as I say, my scenario is that it's going to become very integrated, and we're all going to be enhanced by AI, rather than the AIs over here, and humans over there. But nonetheless, there are existential risks, there are subtle risks, like maintaining privacy, and there's profound benefit. We really have the opportunity to overcome the major challenges that humanity has struggled with for millennia. And it's not easy. For example, autonomous weapons -- it's easy to say, "Oh, let's ban them," but the same drone that's delivering medicine to a hospital in Africa could be used by a bad actor to blow up the hospital. These are dual-use technologies. So it's not simple, but I do think it's solvable. Basically, the challenge is, that needs to be a very high priority as we develop and utilize this technology. And it's not just for the technologists, it really becomes a social, economic, political issue that everybody needs to be engaged in.

CA: Ray, all you've done is give us a superbold prediction and give us incredible insights on the single most important technological force shaping our future. I'd say, not bad for an afternoon. Thank you. Thank you so much, Ray Kurzweil.

(Applause)

(Music)

This week's show was produced by Sharon Mashihi. Our associate producer is Kim Nederveen Pieterse. Special thanks to Helen Walters. Our show is mixed by David Herman, and our theme music is by Allison Leyton-Brown. In our next episode, a conversation with Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, about how we can better understand our own minds.

(Recording) Daniel Kahneman: What makes people happy in terms of experience is primarily spending time with people who you love and who love you back. What makes people satisfied with their lives is much more conventional. You know, it's success. And it's also having a meaningful life.

CA: That's next week on the TED Interview. Before I go, I would just love to say something quickly about why we're actually doing this. Now, not everyone knows it, but TED is actually a nonprofit organization with a simple mission: to spread ideas that matter. Normally, we do that through short TED Talks, and this podcast series is an experiment at taking the extra time to go much deeper. So we'd love to know whether it's working for you. Do you like it? If so, we'd love you to share it with your friends, and also to rate and review it on Apple Podcasts or wherever you're listening. I read every single review and love knowing what you think. So thank you for listening, and thanks for helping spread ideas.