Chris Anderson: Welcome to the TED Interview. I'm Chris Anderson. This is the podcast series where I sit down with a TED speaker, and we get to dive much deeper into their ideas than was possible during their TED Talk.

(Music)

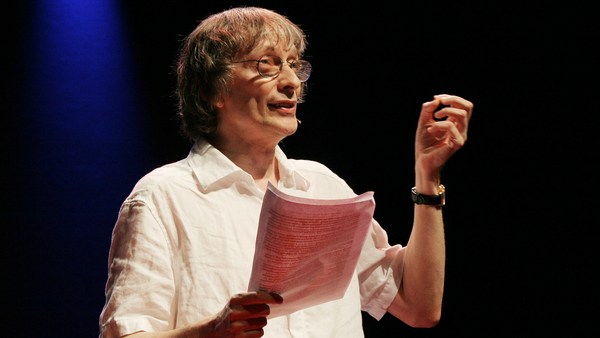

Today's guest is something of a personal hero: David Deutsch. He's a physicist, an author. He has a reputation of being something of a reclusive genius. He lives by himself in a home in Oxford working late into the night, trying to unpack really, the deepest mysteries of the cosmos. His thinking has really had a dramatic impact on how I see the world. Here's the thing: most scientists would tell you that human beings just aren't that significant. We are just this little speck of dust on a random planet, in an obscure part of the universe. David Deutsch says that's wrong. He actually says people matter, and the reason they matter is that they are incubating something: knowledge. In David's view, knowledge is a force of almost unlimited power in the universe and also a force that will determine our future.

David Deutsch (from TEDGlobal 2005): We can survive and we can fail to survive. But it depends, not on chance, but on whether we create the relevant knowledge in time. The overwhelming majority of all species and all civilizations that have ever existed are now history. And if we want to be the exception to that, then logically, our only hope is to make use of the one feature that distinguishes our species and our civilization from all the others; namely, our ability to create new explanations, new knowledge, to be a hub of existence.

CA: David's thinking about knowledge has had a huge impact on me personally. In a book called "The Fabric of Reality," David argued that the way in which we think of knowledge as broken up into all these different fields is misguided. Actually, all of knowledge is connected, and if we spent a bit more time understanding those connections, understanding the context of what we know, that is where real understanding comes from, where the real breakthroughs come from.

Believe it or not, I honestly think it was reading that book that finally gave me the courage, 18 years ago, to leave my company and take over leadership of TED, which back then was an annual conference in California, devoted to bringing together technology, entertainment and design. You see, if Deutsch was right, the sharing of accessible knowledge between different disciplines wasn't just a short-term fad and wasn't just limited to those three subjects. It was something the world would always need. So, he inspired me to take the leap. And here we are. And honestly, David, it's an honor to be speaking with you today. Welcome.

DD: Well, it's very nice to be here, and thanks for the dramatic introduction. I'm very glad to hear it.

CA: So David, in the first TED Talk you gave, you had this phrase that you quoted, really, from Stephen Hawking. Stephen Hawking referred to humans as basically "chemical scum" on the surface of an obscure planet. And that's actually quite a common view of how science is thought of as treating humans, you know. We started thinking we were the center of everything, and then we gradually discovered that, no, we're just a planet revolving around a star, and then that star is just one of a hundred billion in a galaxy, and that galaxy is one of hundreds of billions of other galaxies, and goodness knows ... We become, very quickly, completely insignificant. You, I think, disagree with that characterization. Explain why.

DD: I do, and you're right that that's the prevailing view, because that's the view that's kind of forced on us by a narrow conception of what science is. According to that view, you classify things in the universe in a sort of hierarchy of more massive and powerful versus less massive, and so on. And so, we're used to the fact that the big objects, like the supermassive black holes in the center of a galaxy affect a star, can rip a star to pieces, but the star being ripped to pieces hardly affects the supermassive black hole. And it's the same with the Sun and the solar system, you know, the Sun affects the Earth, but the Earth barely affects the Sun, and so on. But the funny thing is, on Earth, on the surface of the Earth, everything's the other way around. Everywhere you look, you see the effects of life on Earth, and life -- every living thing that you see is the result of the action of a single molecule or two molecules or something, depending on what kind of organism it is. So this submicroscopic entity commands vast resources. Now, humans take this to a wholly different level, where we are capable of becoming cosmically significant, not just dominating the surface of a planet, but dominating the galaxy and further out.

CA: Well, how so? You mean by kind of Star Trek-like exploration or something else?

DD: Yes, Star Trek, or rather, colonization. It's what we do. Humans evolved, unlike all other existing organisms, to find new environments which are initially lethal to them and to change the environment such that they can live comfortably there. Here I am, sitting in Oxford, and if it weren't for technology, I would die within hours, because without clothes, without shelter, without medical attention, without sources of food from far away, I would be very hard put to it to forage. And the territory here supported only a tiny number of people in the early days of our species, whereas now, it supports tens of millions.

CA: And so, the difference between your survival and otherwise is human knowledge turned into technology, which has built the house, the central heating, the clothes and so forth, that keep you alive.

DD: Yes, fundamentally, it's knowledge.

CA: And when you talk about, you know, like, that humans can have indefinite impact on the universe through Star Trek-like expansion out, at first glance, a lot of people listening to that will say, well, already that's sounding a little silly, that's science fiction anyway, and how can that possibly mean much? But your whole second book, this idea of "The Beginning of Infinity," is arguing that knowledge, in principle, has infinite reach, and therefore, if you don't include that in your worldview, you are missing out on something fundamentally important. Talk a bit more about how we could think of that reach of knowledge.

DD: Perhaps it's more illuminating to think of this the other way around. Suppose there were some extraterrestrial beings, intelligent beings, looking around at the stars from, let's say, 100 light years away or something, in the galaxy. And they would see various stars, and they might use astrophysics to predict what these stars will do. But on Earth, they would detect something, for example, the fact that there's oxygen in the atmosphere, which tells them that there’s life here. And then they would detect, if they kept watching the Earth for a while -- I mean, I'm kind of imagining them with technology similar to ours -- they could detect more if they had better technology. But if they watched the Earth for a couple of decades, they would see that the mean temperature of the planet is changing faster than it possibly could. Only artificial intervention can change the temperature of the Earth as fast as it has been changing. This is inexplicable without the presence of intelligent beings. And if they then asked themselves, "Well, this influence, the influence that affected the atmosphere of that planet, could it possibly affect us?" And the answer is yes, because the issue of whether a spaceship can get there is a matter of what we decide to do. And it's also a matter of the laws of physics.

CA: So, David, I think it's important, almost, to having this conversation to, you know, bear in mind that the way you think, by thinking in sort of theoretical terms about what knowledge might, in principle, one day do, that has implications for how we should think of human beings and our role in the world. And so, when we talk about aliens and we talk about, you know, the potential for exploration, you're not saying that, "Hey, this is going to happen anytime soon." What you're saying is, "It is, in principle, possible for this species that has evolved on Earth to have a future that is imaginable -- it may not happen, but it is imaginable -- where it can become indefinitely more influential in our solar system, eventually, maybe our galaxy, and maybe beyond that." And so it's that fact that that is possible in principle, which creates this anchor, this fundamental idea that knowledge -- there's no limit to how powerful an influence it can eventually have, starting with Oxford and central heating and moving out, in theory, indefinitely beyond. And that is a remarkable fact that needs explaining.

DD: Yes, you asked about the cosmic significance, so the answer that I give to explain it, in some sense, must involve things beyond everyday life. But everyday life as we see it would have been regarded as completely magical even a few centuries ago, let alone for the most of the period of the human species.

For example, I can sit in Oxford and look a bit beyond my house and look up in the sky and I see an airplane there. Now, the fact that a metallic object weighing 100 tons is flying there at 500 miles an hour and has come from another continent -- that is as much of a jump from natural human beings, as what we're discussing, this kind of space travel, space exploration is from where we are now. In fact, I think, comparing those two, I'd guess we have already come further in terms of knowledge than what lies between us and space exploration. I'm not saying exploring the galaxy -- that would require more knowledge. But that's all it requires. If you're a scientist, and you're asked, is so-and-so possible, you have to use laws of nature. You can't say, "Well, my intuition is that that will never happen." Because our knowledge of the laws of nature is far superior to our intuition, which, after all, was formed in the past and was formed in a very narrow set of circumstances.

CA: And so, this is really a radical counterview to what I would say is even a traditional biologist view, which is that we should be more humble as a species, you know, "Yes, we have our extraordinary skills, but frankly, every species has its extraordinary skills. We're good at language, and we can build these amazing things, but, you know, an elephant has thousands of muscles in its trunk, and the exquisite way in which it can manipulate that -- that's like nothing else we can do. Ants and bees have these extraordinary social lives ... Every species is, actually, in a very real sense, equally evolved as we are, because it's been evolving for exactly as long from the original source of life on Earth. So there is no special status in biology to humans, and we should come off our high horse."

Now, the implication of what you're saying is, actually, that's not quite right; that knowledge, which somehow became part of the human evolutionary story at some point, is special and allows this particular species to do things that are not just a different kind of thing from others, but different in principle.

DD: Yes. First of all, what gives living things their miraculous power compared with nonliving things, compared with most of the things in the universe, is, likewise, just knowledge. Knowledge is encoded in what is really a computer program in the DNA molecule.

CA: Ah, so in your articulation of it, knowledge is something much broader than a worldview that is encoded in a human mind. It's much broader than that.

DD: That's right. Knowledge isn't just a matter of belief, and it's not just a matter of human psychology. It is information that has causal power.

CA: Knowledge is information that has a causal power. That's a beautifully crisp definition.

DD: I've gone through about three or four definitions of knowledge in my thinking about this, and that's my present one. I get this more general concept of knowledge from the philosopher Karl Popper, who spoke of knowledge without a knowing subject. And the two main types of knowledge that he was interested in were scientific knowledge in human minds on the one hand and knowledge in the form of adaptations in genes of living organisms on the other hand. Now, that second type of knowledge is not knowledge in a knowing subject. But nevertheless, it's information that is spectacularly honed for its ability to cause physical effects.

So, the genes for the eye can cause physical effects of focusing, which can then change the trajectory of the animal, which can then make it kill another animal or escape from another animal and so on. And the program in DNA has punched above its weight by a vast factor. Now, humans can transcend that in at least two ways. One is that the amount of information in our brains is vastly more than the amount in our DNA. So the DNA has built up knowledge by evolution and so on, but we have added to that, both by culture and by individual thinking. And the brain simply holds more bits of information than DNA does. And the other thing is, which is more important, that humans have a different kind of knowledge; namely, humans have explanatory knowledge. Humans have understanding. And I argue in my second book that explanatory knowledge is the stuff that has infinite reach. It seems unlikely that biological evolution could ever, let's say, move an animal to the Moon and back. But we know that human-type knowledge, explanatory knowledge, can do that.

CA: That's really powerful. So what happened at some point along the evolutionary chain is these minds were created that were capable of a different, more powerful kind of knowledge, explanatory knowledge. So this seems to me to come right, then, to the heart of why you believe we are not just chemical scum. And to me, it's a profoundly inspiring view in many ways, of how we can think of who we are, which is that, for whatever reason, we have found ourselves in this moment in history where we have embarked on a journey that has potentially unlimited reach. It could lead us to literally anywhere; there is no dream that, in principle, humans couldn't dream of being part of. And it may be it's not us in the end, it's some successor species. But we are part of a liftoff that has no limit, in principle.

DD: Well, it has the limits of the laws of physics.

CA: ... other than the laws of physics. I think it's a very striking view.

DD: Humans evolved the ability to do what you've just said at least 100,000 years ago.

CA: Right.

DD: But for various reasons didn't use it. Now, in much the same way, the whole universe, starting 14-point-something billion years ago, for the first billion years or so, all sorts of new things were happening. Supermassive black holes were forming, galaxies were forming, hydrogen was ionized and deionized, and then new elements were formed and so on. After about -- I think it's about a billion years, I could be wrong, something like that -- nothing new happened in the cosmos.

(Chris laughs)

Stars were formed, they exploded, planetary systems were formed, the same new elements were spewed into the interplanetary gas, again and again and again, and it was just boring, for about 13 billion years. And then, creativity happened. And we are at the phase change where things are, from now on -- and that is, if we play our cards right; it might not happen, or someone else might do it -- but this phase change changes the whole nature of the cosmos. For example, in the first 14 billion years, the rule was that big things affect small things, and small things do not affect big things much. After the phase change, everything is determined by small things -- small things affect large things, and what is the determining factor is not mass or power or energy, but information; specifically, the kind of information that has physical effects, namely, knowledge.

CA: Well that's the most thrilling history of the universe I've actually ever heard. But you used a word in there that I need you to explain now. You said, "13 billion years, 12 billion of those were boring, then creativity happened." So what was creativity, and how did it happen?

DD: Well, human-type creativity is different from the creativity of the biosphere, in that human creativity can form models of the world that say not only what will happen, but why. So an explanation, for example, is something that captures an aspect of the world that is unseen. So, explanations explain the seen in terms of the unseen, whereas biological knowledge, it's only what works -- the eye is like a camera, because it gradually moved towards that shape, because the animals that had a worse shape, didn't survive as well.

CA: Right.

DD: But a camera is shaped by the laws of optics.

CA: OK, so, the reason for the existence of a camera is because some human somewhere had this explanatory theory based on these ideas about the invisible, these ideas about optics, about physics, about how light works, and by using that pattern of ideas, that allowed them to build cameras, and then a lot more beyond that.

DD: That's right. That is what allows human-type knowledge to have this universal reach, whereas biological knowledge, although it has enormous reach -- as you said, it can make elephants' trunks and giraffes' necks and so on -- it is actually limited because of the type of knowledge it is.

For example, to evolve from one animal to another, over, let's say, 1,000 generations, every single generation must be viable as an animal, because the DNA strands have to be able to just replicate in every single generation. And if one of them fails, if one of them doesn't work, then the species will go extinct, whereas humans, as the philosopher Karl Popper said, we can let our ideas die in our place. And that means that we can go through a sequence of ideas that aren't viable, on the way from one viable idea to the next. We don't have to die when they're wrong.

CA: What was the key thing that happened, though, in human history or in human evolution, that allowed this type of explanatory knowledge to take off?

DD: Almost certainly, this dates back to our ancestor species. Species before humans also had the capacity for explanatory knowledge, I believe, and also our cousin species, like Neanderthals. And I have a rather heterodox theory of why we have this ability. Namely, it's needed to pass on cultural knowledge. This is what Richard Dawkins calls "memes." We evolve cultural knowledge, which is memes, instead of genes, and they can evolve thousands of times faster.

CA: So what happened at some point hundreds of thousands of years ago was that hominid minds evolved the ability to mimic each other. You would see a pattern in another mind and you would copy it, and that created a replication process that was massively faster than traditional reproduction, and it allowed multiple things to be explored, essentially, and some of those started to work.

DD: The first thing that happened, even before that, there are some species still today, like chimpanzees and so on, that have memes, and they replicate the meme from one individual to another by, literally, by blind replication. They have mirror neurons and that kind of infrastructure in their brain which allows them to mimic what another chimpanzee is doing. Now, our ancestors somehow latched on to the evolutionary advantage of having memes, but they both vastly increased the memory, but then they also evolved creativity, because humans copy other humans by a completely different method to what's used by, say, chimpanzees. Humans don't copy the behavior; they copy the meaning of the behavior. So you can watch someone doing something -- let's say you're a safecracker, and you're secretly watching someone opening their safe, and you look at the combination that they enter, and then they turn one wheel and then another wheel. Now, you might go there and do the same thing. Or, you might open the safe by a different method. You know, you might be lowered in, like in some of those film, you might be lowered in from the skylight, and have to turn the knobs with your feet. Now, a chimpanzee could not do that, because that's not copying the behavior, that's just copying the meaning of the behavior. But to humans, it's second nature to copy the meaning. In fact, if you go to a lecture, and you understand what's in the lecture, you might go and tell someone else, but almost certainly not in the same words that the lecturer used. You would explain it in your own words if you understood it. And if you didn't understand it, then you might explain it in the same words the lecturer used. You might say, "Well the lecturer said so-and-so, but I don't know what the hell he was talking about, can you tell me?"

CA: Got it. So let me put this together and see if I've got this right. So, some of our ancestor species developed this ability to copy memes. Memes, by the way, the term is now used often just to mean sort of internet images or animations that take off and are spread virally, which is a very narrow interpretation of Richard Dawkins's original intention, which is, a meme is anything that can be copied from brain to brain, whether it's an idea or a phrase, a poem, a piece of music -- anything that can be copied is a meme. And so, this took off as a sort of biological ability in our ancestors. And then at some point, it shifted to a whole gear, where it wasn't direct copy of behavior; the meaning of what underlay some of these activities started to get copied. And that's the moment when, I guess you would say, understanding comes into the equation. There, someone is understanding someone else's intent or action and doing something based on that understanding. And understanding is, I think, everything, almost, in your view of the world. Say a bit more about what it is to understand something.

DD: I use the terms "understanding" and "explanation" almost interchangeably. An explanation is something that explains what you see in terms of what you don't see. It explains what might happen in terms of general ideas about what can happen. Understanding transcends the initial application of what it's for. Let's say you initially learn how to throw a ball from one person to another for fun, or you throw it as a weapon or something like that. But then later, someone can ask what path does the ball take, and then that may allow them to construct a better weapon or a better defense, or a million other things in future generations, which all depend on the meaning and may have nothing to do with the original application. But I should add that this initial burst of understanding or creativity into the world was blighted by the fact that memes tend to evolve. Like genes, memes tend to evolve to breed true. That is, memes which can get themselves faithfully copied are preferred to ones which can't, so --

CA: Regardless of whether they're true or not?

DD: Right, that's their tendency. That's what they tend to do. And so initially, creativity was used only for copying ideas faithfully, which is almost the opposite use of what we consider creativity to be used for today, which is to improve upon ideas. This is why our ancestors spent 100,000 years basically doing nothing --

CA: (Laughs)

before very, very slowly, they changed their lifestyle, first, better tools and so on, and then agriculture and civilization and so on. But sill, improvements were extremely rare, so that most people, most humans, did not experience any improvement in their lifetime.

CA: And so, what's an example of a meme that could be reproduced but is basically not true, does not conform with -- it doesn't give any value to helping someone understand the world better?

DD: Ah, well, Richard Dawkins's favorite example of this and maybe the reason why he introduced the concept, is religions. I mean, you don't have to be an atheist to understand that most religions are memes, and that they are false. So it could be that there's -- let me concede that there could be one religion that's true, but that would mean that the others are false. But also, much more prosaically and, I guess, importantly, we don't expect any of our knowledge to be completely true. You know, Newton's laws were thought to be the last word in mechanics and gravity and dynamics and so on, for hundreds of years. And then they were overturned in quick succession by Einstein's relativity and by quantum theory. And now we know that they are false. Now, they are still knowledge; knowledge doesn't have to be true, it just has to contain some truth enough to be useful.

CA: And so the key, one of the key contributors, then, to this takeoff was the development of processes that could distinguish between memes that were just reproducing and memes that actually were closer to the truth. In other words, there was this error-correcting mechanism started to take off.

DD: Yes. So we have to jump forward like 100,000 years or some hundreds of thousands of years, to the scientific revolution. It's rather arbitrary where you date it to; some people might say the Renaissance was the beginning of it. And I think that this renaissance or revolution or enlightenment, as I call it, tried to happen several times in human history, right back to antiquity. And in each case, the static-type memes, which prevent innovation, won the battle. And sometimes it lasted one generation, sometimes it lasted two generations, like in ancient Athens or something. And then, with the scientific revolution, it took hold. And it has now been around for, depending on how you count it, it's been around for 300 years, 400 years, something like that. And it's been exponentially improving ever since.

CA: This is really interesting to me. I think it's easy to see just how big a deal this is, that in a way, you had a species that for hundreds of thousands of years had developed this extraordinary ability to have a mental life, but it was effectively running around in random directions, not making real progress, because there was no way of saying, this is actually the way forward. And what you're describing as what science did, was it said it found a way of gradually cutting out the negative signals where someone was running into a brick wall or running backwards, and saying, no, no, cut that out. And so that creates this process whereby we gradually start to get closer to an understanding of "reality."

DD: Even without the quotes.

CA: Even without the quotes.

DD: There really is understanding of reality.

CS: There really is a reality out there, and it matters that we slowly start to model it in some ways, in our minds.

DD: Now, error correction is an extremely simple concept, although very profound. Absolutely everything depends on it, since everything depends on knowledge. And knowledge doesn't come to us on a silver platter. So everything depends on error correction. But although that's a simple fact, arranging for that to happen is not at all simple. It's incredibly sophisticated; we do not understand it. We don't understand it either on the level of how creativity works in a single human mind, and we also don't understand what it takes in a culture for the culture to support error correction, because it's almost paradoxical: what we want is a system for correcting traditional knowledge, but tradition, by definition, is something that stays the same over generations. And so Karl Popper coined the phrase "a tradition of criticism." This is an extremely unusual form of tradition. It's happened very rarely in human history. And the one we call the scientific revolution is the ancestor of everything good we have today. But we don't know what it takes for a culture to have a tradition of criticism in it. Now, we are very lucky and we take for granted that we have things like the scientific community, the scientific tradition. We take for granted that if a professor is asked a question in a seminar, and says, "You're not allowed to ask that, just trust me, I'm the professor," he will be laughed at. Although there are many areas of life where he wouldn't be laughed at. But science is one where it's taken for granted that criticism is part of the culture, it's part of the tradition that's passed on.

CA: And so, in many ways, it's a miracle that this ever happened, and there's a sort of a fragility to it. I think it's your view that this type of knowledge liftoff almost happened or started to happen at other times in human history, perhaps during the Greek civilization, and then we lost it. How fragile is what we have right now?

DD: We can't know, because our enlightenment is the first one that's lasted for more than two or three generations. I don't think it got to where it is by accident, I think there is some stability to it. It didn't get to where it is today by not being stable. On the other hand, there definitely is no guarantee. We could choose to end it. We could do the wrong thing repeatedly and end it. Just one thing, though, I would like to say, that when people compare our civilization to other civilizations that have lasted for centuries or whatever and then collapsed, and they compare ours with theirs, like, you know, it was caused by losing self-confidence and then the barbarians at the gates and that kind of thing, I think that's wrong, because none of the other long-lived civilizations in history has had a tradition of criticism. So it's obvious that they were fragile. They were fragile precisely because they couldn't create the knowledge to cope with unforeseen challenges.

CA: But when you look at world today, David, there's people like you and many others in the scientific and other communities who are really driven by respect for science, respect for knowledge. There are many others, and including people in power, who are not, and it can seem that we may forget the importance of our knowledge and ignore it and let go or blow up or destroy much of the preciousness of what we've built. Is that a lens that you have? What are you most concerned about as you look out at the world right now?

DD: Well, I think it has always been true, since the Renaissance, since the scientific revolution, wherever you count the beginning of our enlightenment to be, it's always been true that most people haven't appreciated it. Most people have values that kind of contradict it. Most people resent it a bit. So it has survived by being stable in its own terms. And when you start referring to the political side of it, there, the equivalent of the scientific revolution is liberal democracy or whatever you want to call the values that underlie the Western political system. And this does seem, especially the Anglosphere part of it, does seem to be incredibly stable. If you look at the early to mid 20th century, the age of the great dictators, totalitarian ideologies were sweeping the world, all the intellectuals in the world were either fascists or communists -- well, I'm exaggerating, but many of them were. And in many countries, fascists and communists took over the government and caused all sorts of damage. And if they had won, they could easily have ended civilization. But I think it's extremely significant that not one of the Anglosphere countries fell to a dictatorship.

CA: And when you say that democracy is the political equivalent of the scientific revolution --

DD: Liberal democracy.

CA: Liberal democracy, yes. I guess the key point you're making there is that you can think of a democracy, a liberal democracy, as an error-correcting system. That is actually the most fundamental way to think of it. It's not that it --

DD: That's exactly what it is.

CA: It doesn't automatically create good. What it does is it eventually, eventually, weeds out the bad. And so, if you imagine human political endeavor, human endeavor generally, as this sort of 1,000 flowers flourishing and trying to grow in different directions, when some of them start to grow in the wrong direction, a democratic system will reign that in and say, "Sorry, you've had your turn, you're out. Let's put someone else in and try and grow differently."

DD: Yes, peacefully.

CA: Peacefully.

DD: That's the thing, because if it's not done peacefully, then knowledge is destroyed in the war or the civil war or whatever or in the coup that overturns the previous regime. The political tradition is judged by whether it can remove bad policies and bad leaders peacefully.

CA: So when people worry today about a rise in demagoguery, for example, you're reasonably confident that the system's error-correction mechanisms will kick into gear?

DD: Yes. I mean, I can't say how little I am concerned about that danger. If civilization is going to be destroyed, it's not going to be destroyed by some government taking power and then not relinquishing it. That's not going to happen.

CA: Well, that's definitely encouraging, and I think a lot of people will be sitting there, crossing their fingers, hoping you were right on that one. I think you think of the realm of the total amount of knowledge and understanding out there as essentially infinite, right? It's not like we'll discover the grand equation and suddenly we'll know all of science; that we should rather think of knowledge almost as this growing sphere against the unknown, and the more we know, the more we know we don't know. Is that the right way to think of it?

DD: Yes. As again, Karl Popper put it, solving problems creates new problems. And therefore, in our infinite ignorance, we are all alike. And maybe the reason why knowledge of the human type has this infinite scope and could take us, you know, across the galaxy or whatever, and also, you know, down to nanotechnology and all that, is because of the special relationship that human minds have with the laws of physics. It's this explanatory knowledge that human minds are capable of, that can see beyond the visible. So we can look up in the sky and see a cold, tiny dot of what looks like cold white light. And we know that that is actually a star, which means it's actually a million miles across, and it's 25 million degrees in its interior and 6,000 degrees on its surface. And if we went there, we'd be fried to a crisp. So we can never experience it, at least not without special technology, and yet, we can know about it. We can sit here and know about it in enormous detail and in ever-increasing detail. The reason that this is possible, as I said, is because human minds and explanatory knowledge have a special relationship with the laws of nature.

CA: So, this seems implausible to a lot of people. A lot of people would say, look, every species knows something. A dog knows that a bone tastes delicious, but it doesn't know scientific theory. We know a certain amount of scientific theory, but it's ridiculous to imagine that we could know you know, that there must be a whole world of things out there that we are never even in principle capable of understanding. And you dispute that. Why? Why?

DD: There are two sides to that comparison. First, you compare the dog with a human, and then you compare with a human to the putative unknowable things that might be out there. So, there are two steps there. I've already explained why the dog is inherently different from us. It's because the dog knows that the bone tastes good because some of its ancestors who didn't know that, died. And the dog doesn't actually know anything, its genes know that. And there are certain types of things that can become known that way. But the vast majority of things in the world, in the universe, cannot become known that way, because the dog cannot try to eat the Sun and be burned and that kind of thing. No one could gain knowledge of the Sun by that same method. Now, the other thing, what if there was knowledge out there, things out there, that we couldn't possibly understand? Well, as a logical possibility, of course, it's always possible that there are incomprehensible things in the universe. But I have argued that taking that seriously is exactly the same as a belief in the supernatural, because you could never have an explanation of the form, this thing that can have an effect on us, can never be understood, because if it can have an effect, we can theorize about what causes the effect, and we can do an experiment to test the theory.

CA: And it's your belief that the type of explanatory knowledge that we have can wrap around any imaginable explanation that could be out there. There is sort of human knowledge, and then there might be some knowledge that gods or fairies or whatever have, that is fundamentally different and more profound, or other aliens could have. So this makes me wonder whether in your worldview, there are similar liftoffs happening on other planets out there.

DD: We don't know. As you know, there's this problem of: if there is intelligent life on other planets in the galaxy, there are many arguments that say we should have seen them by now. This is called the Fermi paradox. Although, I would rather call it the Fermi problem, because I didn't see anything paradoxical about it. Suppose that there are just two explanatory species in the galaxy. Then, having reached the explanatory takeoff, like the scientific revolution, in the twinkling of an eye, on the cosmic scale, we would have settled the whole galaxy. And the galaxy exists on time scales of billions of years. So, compared with the age of the galaxy, the moment from when humans first evolved to when the humans have settled the whole galaxy is just a blink of an eye. And therefore, the chances that two civilizations emerge at the same time is infinitesimal. So that means that if they exist, they must be millions of years ahead of us. And if they're millions of years ahead of us, why aren't they here already? Because the argument said that they would be here already. Now, why would they not be here? Well, there are lots of reasons. First of all, one solution to the Fermi problem might be that we are the first. OK. People kind of reject that because it's kind of boring. You know? And why should we be so special? Well, someone had to be, and we kind of reject that as a possibility, because there's no structure in that idea. There's nothing further to say. But it could be true, like a load of other things. So the next possibility is, yes, the galaxy is full of civilizations, and they're going to be here soon.

CA: But you believe that human creativity is a fundamental part of the whole knowledge liftoff. And the esthetic expression of that is certainly a big part of who we are. To me, one of the puzzles is not that we don't see spaceships coming, it's that we don't see any evidence of the galaxy having been engineered. You know, if dolphins were to make a breakthrough and start developing periscopes that could look up and examine the world around them, and they poked them up and looked at the surface of the Earth, they would see buildings and astonishing structures that seem to cry out for an explanation, that look like they were the objects of intentional construction. We look out at the galaxy and see nothing, you'd think at the very least you'd see some sort of -- you know, some stars had been converted into a spectacular artistic displays, or there'd be some evidence of engineering. The fact that there's no evidence of engineering suggests that the main game in town out there is still the same old physical processes that filled the prior 13 billion boring years.

DD: Yes. Well, so, first of all, we haven't looked very carefully yet. I mean, this kind of thing, looking out for evidence of technology in other star systems, is only just beginning now. And we can only detect very powerful things. And I don't think that we should take for granted that these type -- although, I think we should take for granted that if an intelligent species exists, it will colonize the galaxy very quickly -- I don't think we should take for granted that it will enter this phase of type-one, type-two, type-three civilizations, for the simple reason that once you're a type-three civilization, what are you going to do next? And certainly, they will be capable of doing that. But again, like us, they will have to decide what to do. There would have to be a reason why they go for, for example, enormously increased power consumption. They might not want that. I think the chances are they won't want it, because they will be information-based, they will be entirely in virtual reality, except when they want to go out into the physical world for some purpose. And they may not want to go very far from each other, because of the communication difficulty. Unless, again, unless there's a strong reason for it.

CA: That strikes me as a really compelling solution to the problem, if you like, because based on your view, what matters when you have a knowledge liftoff is knowledge. And knowledge can be encapsulated in many forms, which can be vastly smaller, even, than the biological forms in which we are now.

DD: Yes.

CA: And, to me, it's possible to imagine an alien species developing ever more rich forms of creativity in ever smaller spaces, that the whole notion of physical conquest would become just an absurdly old-fashioned notion of what made life interesting. It's like, why bother to do that when you have infinite control over a much smaller structure of information space that you can pattern in any way you want? And so there's almost that conversion of the material into the virtual, that allows infinite possibility right there.

DD: Yes, as Feynman said, "There's plenty of room at the bottom." There are more orders of magnitude to explore in the microscopic world than there are in the macroscopic world, say, across the galaxy. And once you have a civilization that is capable of interstellar travel and extending down to the microscopic, it's not obvious what they will think best from their point of view. The great disadvantage of living in the galaxy is not the size of it, it's the time. It's the fact that you can't have a coherent culture where the parts of it are 100 light years from each other.

CA: Right, so right there, that's a good reason to theorize why growing intelligence would want to actually go smaller, not bigger. So, it's possible that your -- I'm still so taken with your history of the universe, of 12 billion years of boring. Presumably, it's compatible with what you just said, that it might turn out not to be 12 billion years of boring, there might be all these spectacular takeoffs of intelligence, understanding, knowledge, in different pockets of the galaxy or of the universe, but just that we don't yet see that. We're not yet exposed to any of that, of that history.

DD: Yes, there might be. I mean, I myself hope that part of the morality of any advanced civilization would be that they would come and rescue us, as soon as they found out we exist.

CA: But here's another narrative that is compatible with what we see, which is that, as a species takes off and starts developing knowledge, that inevitably, things go wrong at some point, that we inevitably create the technologies capable of destroying us, and it's either in the nature of the dynamics of power or just in the nature of the dynamics of complexity that something horrifying eventually goes wrong. And these attempts of liftoff get wiped out.

DD: So, I'm sure that's not inevitable. And that's for exactly the same reason why unlimited progress is not inevitable. If it were inevitable -- that means if it were true that anywhere in the universe where explanatory knowledge starts taking off, it will destroy itself within, say, 1,000 years -- that would be a law of physics. So if you're going to postulate that there's this law just in order to make your nightmares come true, you may as well just have stuck with believing in goblins and demons.

CA: Although there is this sort of plausible way of thinking about it, just on Earth level, which is that as technologies get more powerful, the stakes get ever higher. You know, we have already invented technologies that, in principle, you could imagine it's not long before a single deranged student in a lab might be able to engineer a virus that could really quickly spread and, you know, take out the human race, but after staying invisible to people, while it cultures and spreads for 30 days and then suddenly -- boom! It's possible to imagine that knowledge brings with it the potential for unlimited destructive power. And that as the sort of Humpty-Dumpty theory of -- you know, it's easier to break things than to make things.

DD: Yes. Of course, that's a possibility, because if it wasn't a possibility, then continued progress would be inevitable, which it isn't. But the knowledge of how to defend civilization against existential threats is also a form of knowledge, which is unlimited. So if we fail to create that knowledge, we're doomed. If we do create that knowledge, we're not doomed. That story is the same as with all knowledge. So the possibility is there for us to create it, for, as I put it, for the good guys to stay ahead of the bad guys.

But also, there is something about the bad actors that makes them progress more slowly. That is, they are enemies of civilization. Therefore, they are wrong. Right? And therefore, they have to be in a state of mind that can tolerate being wrong, and therefore, they can't tolerate a tradition of criticism. In fact, with the realistic ones that you perhaps have in mind, destroying the tradition of criticism is their main objective. That's what their grievance is. So that makes them slower. That makes them inherently trail the good guys. But that's just a tendency, it need not be so that there could be a breakthrough by some of the bad guys, and that's why I say we have a moral obligation to stay ahead of them.

CA: That's a beautifully optimistic argument, in a way. That there is such a thing as a clever devil, but not as a super clever devil, because by being a devil, you're taking away the ability to be truly clever in the long term.

DD: Absolutely right, yes. I can't see any way out of that argument, it's got to be that.

CA: Well, I love that, I love that argument. I truly hope that that one works out. I just want to ask you this last question, David, which is: If you could implant in the minds of the good majority of people on this planet a single idea, what would the idea be?

DD: I think it's got to be the idea of optimism, that all evils are due to lack of knowledge.

CA: Wait, wait, wait. So, you just gave a definition of optimism there, that is not what most people think of as optimism. Most people think of optimism as a feeling of hope about the future. Your definition is different, so explain that.

DD: Well, hope that isn't based on an explanatory theory is rather -- I mean, isn't that what they call a vain hope?

CA: Yes.

DD: It's whistling in the dark. Optimism, as I define it, has to do with knowledge. It's not a prediction of the future, it's an explanation of failure. If you explain failure as being inevitable or due to some insuperable malevolent force or just the way things are, then that's a recipe for stasis, which is a recipe for failure, and eventually, death. Therefore, I think that all failure has to be explained in the form: "The reason we didn't succeed is that we didn't know how to." And the knowledge of how to is, in principle, attainable. We don't have it now, but we could have it in the future, if we do the right thing. In fact, it follows from this whole conception of knowledge that we've been talking about all this time, that optimism has to be true. Otherwise, there would be a limitation, which would mean the supernatural and all that stuff. The arguments are watertight, all the way from the scientific worldview to optimism in my view.

CA: So here's how I would distill this David Deutsch worldview, which I have to say, David, I find quite an inspiring worldview. So, here we are, this homo sapien, and we've had this surprising moment of liftoff, where we're able to create new knowledge, new understanding. But it's a fragile thing, it's full of errors, full of mistakes. If we could inspire everyone out there to adopt the mindset that knowledge was precious and that when things go wrong on our planet, it's not because there's some evil force there that needs punching in the gut and spitting at. It's just because we're not understanding something, and our job and our duty is to seek to understand, to look for those errors, to correct them. And if we were to adopt that mindset, then there's literally no limit to the journey that we can go on together, a journey of growing knowledge and unlimited creativity, and lives of wonder, and so forth. I mean, that's what I take from you, that knowledge is not a thing for schools, libraries or whatever, it's this superpower that humans have developed, if they're willing to look at it the right way.

DD: Well put. I agree. And we must also expect to make lots of mistakes.

CA: Indeed.

DD: Just knowing that the problem is to create the knowledge doesn't mean -- there's not an automatic way of creating it. In fact, it's conjectural; we're going to make many mistakes, that's why we have to set up institutions that can correct them.

CA: And so mistakes should be viewed as gifts, in a way, so long as you learn from them and adjust as a result of them. They're a gift.

DD: Yes, yes. John Wheeler said that our whole problem is to make the mistakes as fast as possible.

(Chris laughs)

CA: You look out at the world, we're certainly getting that part right!

David Deutsch, it's been such a delight to speak with you, and I really thank you for those many, many hours of -- you know, I picture you in that home, just sitting there, dreaming, thinking, puzzling. What you have put together from that, I think, is really remarkable. I hope we can do this again, David. Thank you so much, I absolutely loved this time speaking with you. Bye-bye for now.

DD: Bye, then.

(Music)

CA: This week's show was produced by Sharon Mashihi. Our associate producer is Kim Nederveen Pieterse. Special thanks to Helen Walters. Our show is mixed by David Herman, and our theme music is by Allison Leyton-Brown. In our next episode, I sit down with Sam Harris to discuss whether science can answer moral questions.

Sam Harris: The most important questions in human life are questions we have to be able to talk about. And we have a very large proportion of humanity that is saying, "OK, these most important questions: how to live, how to cause your children to live, and what to die for, these are questions that we're not willing to talk about rationally."

CA: Now, if you enjoyed today's episode, please rate and review on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you're listening. Or find some other way of sharing with anyone you know who is curious.

Thank you for listening.