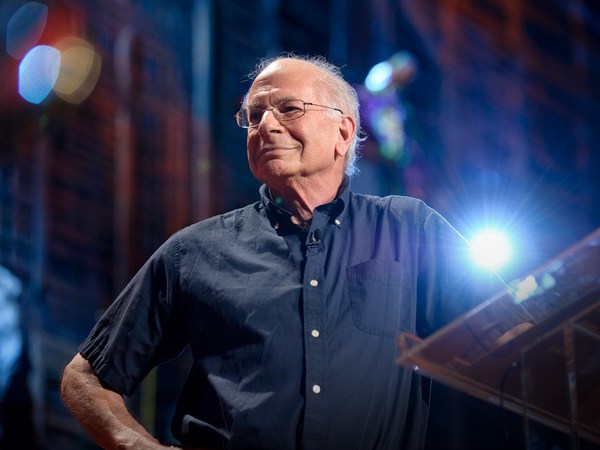

Hello, welcome to the TED Interview. I'm Chris Anderson. This is the podcast series where I get to sit down with a TED speaker, we get to dive much deeper into their ideas than was possible during their short TED talk. Today, I am delighted to have with us Daniel Kahneman. Danny Kahneman is truly one of the greatest minds of our time. He won a Nobel Prize in 2002 for his work on behavioral economics, but his thinking has been influential not just in economics but in psychology and beyond. The thing about Danny is that he understands, more than pretty much anyone, just how weird our minds are. And that means that he has something unexpected and fascinating to say about almost every psychological topic, on everything from decision-making through to something like happiness.

(TED2010) Daniel Kahneman: There is a huge wave of interest in happiness among researchers. There is a lot of happiness coaching -- everybody would like to make people happier. But there are several cognitive traps that sort of make it almost impossible to think straight about happiness, and the first of these traps is a reluctance to admit complexity. It turns out that the word "happiness" is just not a useful word anymore, because we apply it to too many different things.

CA: My goal today is to talk with Danny about how we view our own minds. He's been examining human behavior for close to 60 years, so what an incredible opportunity to look back on some of the insights he's gained over that time and discuss how they apply to our modern age. Danny, welcome.

DK: It's a pleasure to be here.

CA: Danny, you've had this extraordinary life. You're in your 80s now. Tell us a bit about what put you on this path in the first place.

DK: I think I've been a psychologist since I was a child. I really -- I always blame my mother for it, or give her credit for it. She was a very interesting gossip and I loved to follow her gossip -- the sense that people are very interesting and very complicated and that nothing was black or white. I spent a lot of time -- and I had a lot of time during the war -- I spent the war years in France --

CA: Under Nazi occupation?

DK: Yes, under Nazi occupation in [unclear] Southern France, running away from them, and I had a lot of time to myself because I didn't go to school all the time. There were periods where it was too dangerous to go to school, so I was quite an introspective little boy. But I was thinking about psychology, really.

CA: Well, and something amazing happened in Paris that you've spoken about before.

DK: So I was seven years old, it was 1941, there was a curfew for Jews, and we had to wear a Star of David -- a yellow star for which we had to pay with coupons -- the coupons for clothing. And I was visiting a friend of mine and playing, and I was told it was about seven o'clock -- I had missed the curfew. So I put on my sweater inside out and I walked home. And not far from home -- it was a deserted street -- I saw somebody walking toward me and he was a German soldier. Not only a German soldier -- he was wearing a black uniform. That was the uniform of the SS and they were the most frightening of all. And as we came close to each other, he beckoned me and picked me up, and I remember being terrified that he would see inside my sweater -- that he was picking up a little Jew. He picked me up and he hugged me very tight, and then he put me down and took a wallet out and showed me a picture of a little boy and gave me money. So that was a story that fit with what my mother was telling me about people being very complicated and nothing being quite black or white.

CA: No one who you think is evil is completely evil; no one who you think is good is completely good? That was part of it?

DK: That's right, that sort of thing.

CA: And so this idea of the nuance of human nature really does seem to have been a foundation of so much of what you've done because many people go through life with quite a simple picture of humans. Talk about what that traditional view of human nature has been, especially even in economics.

DK: Well, there are many versions of "what makes humans think." A particular version is the foundation of the science of economics and the so-called rational agent model. The assumption's that economic agents are rational. They're also supposed to be selfish and they're also supposed to know what they want, and of course, as a psychologist -- this sounds wrong. And of course, economists know that it's wrong, it's just very useful to their theorizing.

CA: And so was it in the '70s that you formed this extraordinary partnership with Amos Tversky and started to question some of these ideas? Tell us about how that happened.

DK: Our partnership and our friendship actually started in 1969. I had a seminar and I invited Amos to talk to us in the seminar, and he presented work that was not his work, but that was a mixture of the traditions of economics and psychology, and the conclusion they had reached was that humans are good, intuitive statisticians. And I thought that was ridiculous.

(Chris laughs)

DK: And so we had a heated argument -- the Israelis like to argue and it was one of those arguments where, you know, no quarter is given but people really quite like each other. At the end of that argument, we decided we wanted to pursue it. And I think I won the argument, so Amos was interested in following up the ideas that I had expressed, and then we got together and we started collaborating. And then, eventually, fairly quickly, we discovered that we really liked each other and we really liked spending a lot of time with each other. That began an exceptional collaboration that lasted about 12 years.

CA: So give us a hint of it, because the core of the papers that you were publishing back then were around human decision-making and the many ways that we kind of get it wrong, in a sense. Is that right?

DK: Well, we started out asking about judgment under uncertainty, that is, how people assess probabilities, how they make intuitive predictions and how they test hypotheses.

CA: Give us an example.

DK: I'll give you my best example, actually, I think. It's a fairly complicated one, but your listeners will follow. So suppose I ask you to think about a woman -- I'll call her Julie. I'll tell you two things about her: she's a graduating senior at a university and she read fluently when she was four years old. What is her GPA? And a remarkable thing happens here -- every one of you has a number. A number popped into you head.

CA: And a "GPA," for those outside the US, is ...

DK: Is "grade point average." So in the US, it's on a four-point scale, where four is very good. And everybody has a number, and the number comes to mind immediately and intuitively. And we know two things about that number. We know exactly what happens in the mind when the number is produced and we know also, with certainty, that that number is statistically wrong.

CA: OK, so the number I came up with was 3.5.

DK: Well, you were on the low side. Most people say 3.7 but --

CA: That's possibly because I don't know what the GPA stands for.

DK: That's right, you didn't go to school here. I'll tell you what happens, because it's an example of how intuition works. So you hear she was a precocious reader -- quite a precocious reader. And you have an impression of how precocious she was. It's not that you're thinking in percentiles, but you have an impression of how strong it is. And let's say it is in percentiles, so she is somewhere -- maybe the 95th percentile. Now, you also have an idea about the distribution of GPA. And if you picked the 95th percentile for Julie's reading ability, you find the GPA which is also the 95th percentile. And that's the number that comes to your mind. Now this is a very complex calculation. Nobody's aware that this is what they did, but in fact, this is what they do. So they take the evidence, they evaluate how strong it is and then they map the evidence directly on the conclusion and that matching is the result.

CA: And the reason this goes wrong is that reading is only one component of GPA. There are many others, so if judged just on reading, that 3.7 might not be an unreasonable guess, but her actual GPA is more likely to be --

DK: The best guess about her GPA is that it's slightly above average but very slightly above average. That's the best guess, because indeed, reading age is an inferior cue to a person's GPA, and yet intuitively, we predict as if we could predict perfectly, on the basis of weak evidence. That was one of the major findings of our early research.

CA: So this work, and much more -- you've had many other superproductive partnerships -- eventually led, really, to the field of behavioral economics' flourishing.

DK: Well, I'm sometimes described as among the founding fathers of behavioral economics. I am not. I can't accept the credit for that paternity. I'm sort of the godfather. The real father of behavioral economics is Richard Thaler, who got the Nobel Prize this year and is my best living friend. I think he's a genius, I think that the Nobel Prize was overdue and I'm very, very happy he got it.

CA: In the way that you have described your thinking in the book that you published a few years ago, "Thinking Fast and Slow," you talk about these two different systems of thinking that humans have. Can you elaborate on that a bit?

DK: Yeah, you know, it's intuitively very obvious that there are two quite different ways in which thoughts come to mind. So if I say "two plus two," a number comes to mind. And you can see how that number comes to mind; you can feel it. You didn't choose it. You didn't work for it. It just came to your mind. That's intuitive thinking -- that's fast thinking.

CA: And you call that System 1.

DK: I call that System 1. There are many kinds of fast thinking. When you're an experienced driver and you drive, it's System 1-type behavior. Emotions are part of that fast reaction system. But it's both emotion and skills. And then, you have another system, another way of thinking, which is exemplified by what happens if I ask you to multiply 17 by four. Now, you can do it, you can do it in your head, but it will take you some work, and it's that work that defines System 2. The thinking of System 2, that slower thinking, is effortful and it's focused, which means that when you're doing one thing you're severely impaired, or in some cases quite incapable of doing other things. So you couldn't compute 17 times 14 while taking a left turn into traffic -- and you'd better not try, because it would blind you, actually -- if you went on with a computation, you might not see traffic.

CA: So how much can you equate those two systems with actual different parts of the brain? I mean, is System 1 more driven by older, evolved brain structures and System 2 is the sort of frontal cortex overlay on top of that? Or is that not right?

DK: Well, because I don't think of System 1 as being primarily emotional -- I can't locate it. So emotions are localized somewhere else entirely, memory is somewhere else. System 2, which links self-control and intelligence -- that is in the prefrontal cortex. Anyway, we can identify that locus of being active when people reason and when they invest mental effort, whether it be in reasoning or in self-control.

CA: I mean, if you're going to write a book about System 1, System 2, and argue for people that they should understand their own minds better, that is an appeal, really, to the System 2 in people's minds, correct?

DK: Yes, but on the other hand, we have to recognize that System 2 is slow and inadequate, and if we try to let System 2 govern everything we do, we'd be completely paralyzed. I mean, we're dependent on System 1 to cross the street. We're dependent on System 1 to start us eating something and stop us when we're fed. System 1 rules, really, and we can't turn over everything to System 2. What we can do, maybe, is when you realize you're in a situation where you know that you're likely to make a mistake -- slow down and use System 2. But you can only do that sparingly. It is not advice for you to run your life every minute of the day.

CA: So whoever came up with "count to 10 before losing your temper" had a point.

DK: That's exactly it.

(Laughter)

DK: 10 may not be quite enough, but --

(Laughter)

CA: Well, it's interesting, because you developed one aspect of this in a different way when you came to TED in 2010 and gave your TED talk, which was about two selves. I think not the System 1, System 2 selves, but what you called the experiencing self and the remembering self. And I think this came out of -- you'd spent years starting to think about what I think you call hedonic psychology. It's sort of the psychology of happiness and well-being, and discovered some really surprising things when you actually dug into that, including that it doesn't even really make sense just to ask, blandly, whether people are happy. That question is full of pitfalls. Talk about those issues and about the experiencing self and the remembering self.

DK: Well, I'll describe an anecdote which highlights the difference. I was giving a talk somewhere and talking about these things, about experience and memory, and somebody said, "Well, I recently listened to a symphony, and it was absolutely marvelous, and at the end, there was something wrong with the record and there was a loud screeching sound, and it ruined the whole experience." And if you reflect upon that sentence for a moment, clearly it hadn't ruined the experience. He had had the experience -- 20 minutes of glorious music. What it ruined was the memory of the experience. So that indicates that there is a real difference between actual experiences and what we get to keep, what we get to store, and what we get to store are memories. And the memories are often not faithful to the actual event. The emotional memory that we keep -- how much we like the memory, how much we hate it -- that's very strongly affected by how it ends, how the episode ended, like the screech at the end of the symphony. And it's completely insensitive to the duration of the experience, so, almost completely insensitive. So how we feel about memories really doesn't correspond to essential aspects of experience.

CA: This is so interesting to me, because it's not clear to me which self we should be championing here. I mean, you've done this remarkable research -- actually lots of different categories of research that track, in the moment, how people are feeling, and then contrast that with how they report an event afterward. In the TED talk, you talked about these colonoscopies that are longer -- on any reasonable basis, a worse colonoscopy that had more pain over more time, but which eased off the pain towards the end, was reported by those who suffered it as less bad than those who suffered a shorter one that stopped suddenly.

DK: I mean, you can actually improve the memory of a painful medical procedure. These days, colonoscopy is not a good example, because --

CA: They're less painful.

DK: No, no, they don't remember anything. But in the days that we did that research about 20 years ago, going on 25, colonoscopy was really quite painful and you felt every second of it, but it turns out you can improve the memory of the colonoscopy by just adding some time to it, provided that that time was relaxed -- or not completely relaxed, still uncomfortable, but less uncomfortable than before. So you can improve a memory by adding an unpleasant bit to the experience, provided that it's a diminishingly unpleasant bit.

CA: And so you give these other examples of vacations where the vacation that is kind of bad but ends really well will be remembered as better than the vacation that was long and wonderful and then ended in turmoil and that was the worst one, that you then wouldn't choose to repeat that vacation, even though in many ways, that seems irrational. Do you have a view as to which of those two selves -- our remembering self or our experiencing self -- we should use our System 2 rationality to edit and say, "Now wait a sec, don't be taken in by that bug about ourselves"? Should we edit better for experience, or should we say no, it's actually the story is what matters?

DK: Well, I don't have a clear answer to that, but on the vacation, I had a thought experiment, which I think is useful. Which is you're contemplating a vacation, and now suppose I tell you that at the end of the vacation, you'll get a drug that will make you completely amnesic. You won't remember anything and will destroy all your pictures, so you'll have no record of it. Now does that change your vacation plans? And that's an important question, because here, the remembering self says "No, we'll have kept nothing," but the experiencing self will have an intact experience. And if you discover that you will change your plans, that means that you're having memories, you're having vacations to serve your remembering self. That is, you're constructing memories and you want to keep them. I started out the research thinking that I was completely on the side of the experiencing self. I said, you know, there are two things: there is living life and thinking about it, and so you live life most of the time and that's the experiencing self, and occasionally, you stop and you say, "Well, how am I doing? Am I satisfied with my life?" And that's the remembering self. So I thought experience is it, we should measure experience, that's the real happiness. What people think about it really shouldn't matter.

And I held that opinion quite strongly, for a few years, and I gave it up. And the reason I gave it up was that it turns out that this is not what people want. People actually want a story. They want their life to be a good story. And they want to add elements to that story, and those elements are good memories. And so people really treasure memories and want to have them. And so I was faced with the position of holding a view of well-being which didn't correspond to what people wanted. And so I'm now confused, and I admit it. There are those two selves, the experiencing self and the remembering self, and to make them happy, you would have to do different things. It is not the same thing that maximizes the quality of your experiences and that maximizes your satisfaction with your life.

CA: And when you say people want the story, is that both their System 1 thinking and their System 2 thinking wants the story?

DK: Oh, I mean, I couldn't distinguish that. We want the story. I mean, this is very deep. And the way we think of our lives is we think of our lives as a story, which is why, by the way, a deathbed reconciliation seems to matter a lot. You know, people think that this is the very important thing to do. To get back together -- which in terms of experience is nonsensical, but what you have done, because of the importance of ending, you've changed the story.

CA: But it seems really important when it comes to measuring happiness or human well-being, because it seems like there are two fundamentally different research methods that do this, one of which, essentially, is tapping into the experiencing self; it's asking people, at random moments, "What are you feeling right now?" Are you happy, uncomfortable right now?" And then, there's the research that just says to people more generally, "Taking your life as a whole, how happy would you rate yourself on a scale of one to 10?" Which seems to be more about the --

DK: Remembering self.

CA: Remembering self, exactly. Are both those research forms valid? And what do they actually reveal about the world now? Like, how different are they?

DK: Well, I think -- I'm not sure everybody would agree -- but I think I should take some credit for the fact that current research on well-being typically measures both. It measures the emotions -- not by tapping every minute, which is the gold standard, but by asking people questions about the emotions they have experienced. And in addition, they're asked, "What do you think about your life? How satisfied are you with your life?" So both sets of questions are asked, and it turns out that they're different. What makes people happy in terms of experience, I believe, from our research, is primarily social. It's primarily spending time with people you love and who love you back. That's what makes people happy ... in the moment. What makes people satisfied with their lives is much more conventional. You know, it's success. I mean, it's also having a meaningful life. I don't want to define a meaningful life, but having the sense that your life is meaningful is quite important, and certainly, if your sense is that your life is meaningless, then you're probably depressed and you're certainly very unhappy.

CA: There have been all these attempts to try to find a better way of measuring society's progress that somehow bring happiness into the mix. How happy are people? Happiness numbers don't seem to have moved much in America in 50 years, and this is causing distress. How could we measure that better? I think you've proposed that we're looking at the wrong thing, that there's so much ambiguity about happiness measurements generally. A much more powerful thing to focus on would be some kind of misery index -- of minimizing misery.

DK: I mean, I think, if I had my druthers, and I don't -- but I would rename the field. And I think if we said we study misery, it would be a less joyful topic to deal with, but it would be more useful to society, and steps that would be taken to reduce misery would be more acceptable I think, morally, to people, than steps to increase happiness -- mental health, grief counseling, old age.

CA: Danny, it feels like your work has made a huge difference in psychology and in economics, but maybe hasn't yet percolated that far out into other fields, like journalism, like democracy, like just everyday conversation. I'm curious if you have a view on this, whether you think that we could do with much broader understanding of these issues of who we are and how make decisions.

DK: Well, it certainly wouldn't hurt for people to be psychologically sophisticated. If I had to choose a focus, I would choose Walter Mischel's focus: our self-control rather than trying to improve your thinking. I think working on self-control is easier and more manageable and has more immediate consequences than trying to control your thoughts or reduce your cognitive biases. So I'm not a great believer in individuals improving their own thinking. I do believe that organizations can improve their thinking, but not individuals. On the other hand, I think working on self-control seems to be more promising.

CA: There's a lot of hand-wringing at the moment about how people's self-control on the internet, for example, is not that impressive. We seem to be in this culture of gut-driven outrage, instant responses, clickbait, you know, it's arguably driving a cycle of unintended consequences, including people gathering together in clans, where they inflame their own anger at each other. I think you're quite pessimistic about this --

(Laughter)

whether we could change this, but it seems to me, in the seeds of what you've just said, that people learning that they have these two parts to them, and knowing that there are tools whereby they could gain better self-control, wouldn't that, over time, potentially yield a better culture online as well?

DK: Well, I mean, you speak of this as if this was something that we could do. It would certainly be a good thing to do if we could do it, but it would mean changing the culture, it would mean changing the education system, and there would be a lot of opposition. So it's not easy to see. It would be better if people were more reflective, and I think there is no doubt that the ease with which news travels has detrimental effects.

CA: Though quite a bit of it might be doable just by changing the attitudes in some of the big media firms and in the Silicon Valley firms that drive what people see. The algorithms that drive what we see are, arguably designed right now based on a kind of System 1 -- they just observe what people do in the moment, they're designed for fast thinking and they don't give anyone a chance to apply their slow thinking. You've never been asked by an internet site, "Would you actually like it if we shielded you from all the clickbait crap that we otherwise put in your sight to try and make money?" I mean, people might respond to that, and I think that many of the people who are building those algorithms actually have good intent. They think they're operating for human choice. It's just a naive view of human psychology. They haven't read you, they haven't understood that there might be a different way of thinking that some people would actually elect to design for if they were given the chance.

DK: Well, my mother was a pessimist, and so I'm a pessimist, and I always see the dark side of things. I'm not very optimistic about changing the media. I mean, you could change things at the margin, but basically, these are market forces and people are getting what they want. And --

CA: Let me push back on "people are getting what they want." People are getting what they want in the moment of clicking --

DK: Absolutely.

CA: But society as a whole is absolutely not getting what it wants right now, and you can feel that in the huge pushback, so I think redefining what we say by what we want matters --

DK: I was going to make a point about -- think of British tabloids, which are the naked lady on page two and the stories of murders and rapes on page one. That seems to be the popular press. You know, look at the press in New York. People want a certain kind of content, and the media offers it to them. Now, the kind of world in which all the media were like NPR, so many of us would think, "Well, NPR is all anybody needs," but it is not all that people want, and so there are market forces which push media to get people what they want in the moment --

CA: Mhm.

DK: It's very difficult to fight those market forces.

CA: But in the old media world, there were also market forces that created, if you like, quality media that applied different, more reflective journalistic standards. One worry of the current world is that unintentionally, we've built these machines that automatically suck people to -- "You may only have tabloid content. We are going to drive you into an angry person by only seeing the stuff that you will respond to." And I think you could make the case that there's at least some room to open a space for more reflective online media today that reflect the broader balance that there was a few years ago.

DK: I completely agree that at the margin, you can make marginal changes. Whether you can change the essence of the system and, you know, make a really big difference -- that, I'm less optimistic about. People were living in their tribes before the media. It has intensified a certain kind of thing that you're completely oblivious to the other side, and there's that echo chamber effect that the new media produced that is possibly stronger than existed earlier. The phenomenon of political polarization and whether that phenomenon is controlled or caused by what is happening in the media, that's unclear. Or whether, what the media are doing, is they're reflecting the fact that we are in an age of increasing polarization. And my sense of that polarization started first, when you look at the political history -- you know, things started earlier, in the early '90s, the post-Reagan world, and the Reagan world, which many of us, you know -- we didn't think that was such a great world, but in the Reagan world, there was a lot of civility and comity between the parties. There was overlap, and so on. Polarization began in the '90s. It began before the media. The media are just feeding it, they're not causing it.

CA: Well, it's interesting you describe yourself as a pessimist. I definitely am an optimist, but, I would like to think, in the kind of David Deutsch definition of the term, which is not a feeling of hope about the future, it's just a belief that when you have a problem, there's got to be a solution there somewhere, we just have to try and find it. And so definitely, my mind's going to keep worrying on that, in search of that possible solution, even it turns out to be only a marginal one. Let's turn to a slightly happier topic: partnerships. You've had an extraordinary series of extremely productive partnerships in your life, and starting with Amos. Talk a bit about what makes a partnership a great, productive, wonderful partnership.

DK: Well, one condition is that people have to like each other, so they have to like to spend time with each other. I mean, that's for true partnerships. There are different kinds of collaborations. There are some collaborations where different people each bring a particular skill and all the skills are needed, but there is no overlap in skill between the individuals. I have been in different kinds of collaborations where actually, the skill sets overlap. There's something distinctive, and that can be really happy, when people understand each other very quickly, but keep surprising each other. And I've had that several times in my life, and there are few things more pleasurable than that in an academic's life -- than a happy partnership.

CA: How much of a role does humor play?

DK: Oh, you have to be laughing.

(Laughter)

You have to be laughing. Unless it's funny, you can't go on. So laughter is really the lubricant that keeps the whole thing going.

CA: And occasionally, if I'm not mistaken, it sometimes sparks actual ideas, like laughter that you and Amos had, for example, would occasionally spark a research question, or --

DK: Well, I mean, in our case, our research was ironic research. I mean, we studied foibles, weaknesses in our own thinking and in other people's thinking, so the topic of our research was funny, but I've had collaborations on topics that were not specifically funny and where humor was always present.

CA: Mhm.

DK: I don't think you can do really without it. You can't do really good work without it.

CA: Danny, will you talk a bit about the partnership with your wife, Anne? That was a professional relationship, initially?

DK: Well, not quite. I mean, I heard Anne give a talk 51 years ago. She came to Harvard in Cambridge, she was a young PhD from England and she gave an absolutely brilliant talk to a very large audience of Harvard and MIT people. It was sort of an unusual event, and she was pretty and she was nice and I sort of fell for her, and enough so that I changed my line of work and I became more focused on attention, which is what she was studying. So not to chase her, but because I had changed my line of work, I went to conferences where I met her, and over the years, we became friends --

CA: So wait, wait, wait. So you changed your line of work because you were interested in attention or because you wanted to go to conferences where you would see --

DK: No, I changed my line of work because I was interested in what she had done. She was doing fascinating work and --

CA: But it had the happy side effect that you --

DK: It had the happy side effect that we saw each other at conferences and eventually fell for each other.

CA: And now, 51 years later, that's been a long relationship. And you've published together and --

DK: We did, but that was not the happiest of collaborations.

CA: Oh.

DK: Actually, our marriage survived, but we had a very had time together. We published some fairly important papers but we were not -- yeah, we were not very generous intellectually to each other, and we really did not have the same intellectual style.

CA: Danny, you've led a long and extraordinary life. What does your reflective self, your System 2 self, your remembering self make of that life? How do you describe your own life's meaning or purpose?

DK: I have been extraordinarily lucky in all the public aspects of my life. There have been some -- I've been unlucky in other ways, but I've been extremely lucky in my professional life. And the main bit of luck is that I've met wonderful people and they've become friends, and I've worked with them. I attribute it entirely to luck, but it's also the case that I was able to exploit it and to do something with it, but it's mostly my friends. You know, when I look back at the history, it's the friends I've had. I've almost never worked alone, and I've always loved working with others.

CA: Danny, TED's mission is to spread ideas that are worth spreading. If you could inject one idea into the minds of millions of people, what would that idea be?

DK: Don't trust yourself too much. Don't trust in ideas and beliefs just because you can't imagine another alternative to them. Overconfidence is really the enemy of good thinking, and I wish that humility about our beliefs could spread.

CA: Danny Kahneman, it's been an extraordinary treat to have you for so long. Thank you for the generosity of your time and the generosity of your life, and for the brilliance and wisdom you've brought to so many people. Thank you very much.

DK: Thank you.

(Music)

CA: This week's show was produced by Sharon Mashihi. Our associate producer is Kim Nederveen Pieterse. Special thanks to Helen Walters. Our show is mixed by David Herman and our theme music is by Allison Leyton-Brown.

(Music)

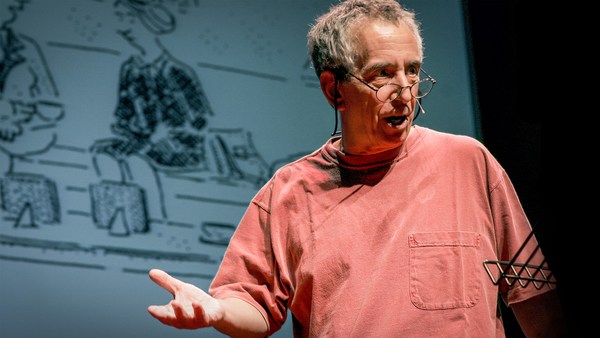

In the next episode, I talk to none other than Sir Ken Robinson, the man who gave our most popular TED talk ever. It's called "Do schools kill creativity?"

(Recording) Ken Robinson: Teaching is an art form, and what it's been reduced to is a sort of delivery system, a kind of service agent for the testing companies. The ones that have been turned around have recognized that at the heart of a school is this idea of a learning community. And a learning community works best when students and teachers are working together collaboratively.

(Music)

CA: That's next week on the TED Interview.

(Music)

Before I go, I just have to say something quickly about why we're actually doing this. Now, not everyone knows it, but TED is actually a nonprofit organization with a simple mission -- to spread ideas that matter. Normally, we do that through short TED talks, and this podcast series is an experiment in taking the extra time to go much deeper. So we'd love to know whether it's working for you. Do you like it? If so, we'd love you to share it with your friends, and also to rate and review it on Apple Podcasts or wherever you're listening. I read every single review and love knowing what you think. So thank you for listening and thanks for helping spread ideas.

(Music ends)