Chris Anderson: OK, Stewart, in the '60s, you -- I think it was '68 -- you founded this magazine.

Stewart Brand: Bravo! It's the original one. That's hard to find.

CA: Right. Issue One, right?

SB: Mm hmm.

CA: Why did that make so much impact?

SB: Counterculture was the main event that I was part of at the time, and it was made up of hippies and New Left. That was sort of my contemporaries, the people I was just slightly older than. And my mode is to look at where the interesting flow is and then look in the other direction.

CA: (Laughs)

SB: Partly, I was trained to do that as an army officer, but partly, it's just a cheap heuristic to find originalities: don't look where everybody else is looking, look the opposite way. So the deal with counterculture is, the hippies were very romantic and kind of against technology, except very good LSD from Sandoz, and the New Left was against technology because they thought it was a power device. Computers were: do not spindle, fold, or mutilate. Fight that. And so, the Whole Earth Catalog was kind of a counter-counterculture thing in the sense that I bought Buckminster Fuller's idea that tools of are of the essence. Science and engineers basically define the world in interesting ways. If all the politicians disappeared one week, it would be ... a nuisance. But if all the scientists and engineers disappeared one week, it would be way more than a nuisance.

CA: We still believe that, I think.

SB: So focus on that. And then the New Left was talking about power to the people. And people like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak cut that and just said, power to people, tools that actually work. And so, where Fuller was saying don't try to change human nature, people have been trying for a long time and it does not even bend, but you can change tools very easily. So the efficient thing to do if you want to make the world better is not try to make people behave differently like the New Left was, but just give them tools that go in the right direction. That was the Whole Earth Catalog.

CA: And Stewart, the central image -- this is one of the first images, the first time people had seen Earth from outer space. That had an impact, too.

SB: It was kind of a chance that in the spring of '66, thanks to an LSD experience on a rooftop in San Francisco, I got thinking about, again, something that Fuller talked about, that a lot of people assume that the Earth is flat and kind of infinite in terms of its resources, but once you really grasp that it's a sphere and that there's only so much of it, then you start husbanding your resources and thinking about it as a finite system. "Spaceship Earth" was his metaphor. And I wanted that to be the case, but on LSD I was getting higher and higher on my hundred micrograms on the roof of San Francisco, and noticed that the downtown buildings which were right in front of me were not all parallel, they were sort of fanned out like this. And that's because they are on a curved surface. And if I were even higher, I would see that even more clearly, higher than that, more clearly still, higher enough, and it would close, and you would get the circle of Earth from space. And I thought, you know, we've been in space for 10 years -- at that time, this is '66 -- and the cameras had never looked back. They'd always been looking out or looking at just parts of the Earth.

And so I said, why haven't we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet? And it went around and NASA got it and senators, secretaries got it, and various people in the Politburo got it, and it went around and around. And within two and a half years, about the time the Whole Earth Catalog came out, these images started to appear, and indeed, they did transform everything. And my idea of hacking civilization is that you try to do something lazy and ingenious and just sort of trick the situation. So all of these photographs that you see -- and then the march for science last week, they were carrying these Whole Earth banners and so on -- I did that with no work. I sold those buttons for 25 cents apiece. So, you know, tweaking the system is, I think, not only the most efficient way to make the system go in interesting ways, but in some ways, the safest way, because when you try to horse the whole system around in a big way, you can get into big horsing-around problems, but if you tweak it, it will adjust to the tweak.

CA: So since then, among many other things, you've been regarded as a leading voice in the environmental movement, but you are also a counterculturalist, and recently, you've been taking on a lot of, well, you've been declaring what a lot of environmentalists almost believe are heresies. I kind of want to explore a couple of those. I mean, tell me about this image here.

SB: Ha-ha! That's a National Geographic image of what is called the mammoth steppe, what the far north, the sub-Arctic and Arctic region, used to look like. In fact, the whole world used to look like that. What we find in South Africa and the Serengeti now, lots of big animals, was the case in this part of Canada, throughout the US, throughout Eurasia, throughout the world. This was the norm and can be again. So in a sense, my long-term goal at this point is to not only bring back those animals and the grassland they made, which could be a climate stabilization system over the long run, but even the mammoths there in the background that are part of the story. And I think that's probably a 200-year goal. Maybe in 100, by the end of this century, we should be able to dial down the extinction rate to sort of what it's been in the background. Bringing back this amount of bio-abundance will take longer, but it's worth doing.

CA: We'll come back to the mammoths, but explain how we should think of extinctions. Obviously, one of the huge concerns right now is that extinction is happening at a faster rate than ever in history. That's the meme that's out there. How should we think of it?

SB: The story that's out there is that we're in the middle of the Sixth Extinction or maybe in the beginning of the Sixth Extinction. Because we're in the de-extinction business, the preventing-extinction business with Revive & Restore, we started looking at what's actually going on with extinction. And it turns out, there's a very confused set of data out there which gets oversimplified into the narrative of we're becoming ... Here are five mass extinctions that are indicated by the yellow triangles, and we're now next. The last one there on the far right was the meteor that struck 66 million years ago and did in the dinosaurs. And the story is, we're the next meteor.

Well, here's the deal. I wound up researching this for a paper I wrote, that a mass extinction is when 75 percent of all the species in the world go extinct. Well, there's on the order of five-and-a-half-million species, of which we've identified one and a half million. Another 14,000 are being identified every year. There's a lot of biology going on out there. Since 1500, about 500 species have gone extinct, and you'll see the term "mass extinction" kind of used in strange ways.

So there was, about a year and a half ago, a front-page story by Carl Zimmer in the New York Times, "Mass Extinction in the Oceans, Broad Studies Show." And then you read into the article, and it mentions that since 1500, 15 species -- one, five -- have gone extinct in the oceans, and, oh, by the way, none in the last 50 years. And you read further into the story, and it's saying, the horrifying thing that's going on is that the fisheries are so overfishing the wild fishes, that it is taking down the fish populations in the oceans by 38 percent. That's the serious thing. None of those species are probably going to go extinct. So you've just put, that headline writer put a panic button on the top of the story. It's clickbait kind of stuff, but it's basically saying, "Oh my God, start panicking, we're going to lose all the species in the oceans." Nothing like that is in prospect. And in fact, what I then started looking into in a little more detail, the Red List shows about 23,000 species that are considered threatened at one level or another, coming from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the IUCN. And Nature Magazine had a piece surveying the loss of wildlife, and it said, "If all of those 23,000 went extinct in the next century or so, and that rate of extinction carried on for more centuries and millennia, then we might be at the beginning of a sixth extinction. So the exaggeration is way out of hand. But environmentalists always exaggerate. That's a problem.

CA: I mean, they probably feel a moral responsibility to, because they care so much about the thing that they are looking at, and unless you bang the drum for it, maybe no one listens.

SB: Every time somebody says moral this or moral that -- "moral hazard," "precautionary principle" -- these are terms that are used to basically say no to things.

CA: So the problem isn't so much fish extinction, animal extinction, it's fish flourishing, animal flourishing, that we're crowding them to some extent?

SB: Yeah, and I think we are crowding, and there is losses going on. The major losses are caused by agriculture, and so anything that improves agriculture and basically makes it more condensed, more highly productive, including GMOs, please, but even if you want to do vertical farms in town, including inside farms, all the things that have been learned about how to grow pot in basements, is now being applied to growing vegetables inside containers -- that's great, that's all good stuff, because land sparing is the main thing we can do for nature. People moving to cities is good. Making agriculture less of a destruction of the landscape is good.

CA: There people talking about bringing back species, rewilding ... Well, first of all, rewilding species: What's the story with these guys?

SB: Ha-ha! Wolves. Europe, connecting to the previous point, we're now at probably peak farmland, and, by the way, in terms of population, we are already at peak children being alive. Henceforth, there will be fewer and fewer children. We are in the last doubling of human population, and it will get to nine, maybe nine and a half billion, and then start not just leveling off, but probably going down. Likewise, farmland has now peaked, and one of the ways that plays out in Europe is there's a lot of abandoned farmland now, which immediately reforests. They don't do wildlife corridors in Europe. They don't need to, because so many of these farms are connected that they've made reforested wildlife corridors, that the wolves are coming back, in this case, to Spain. They've gotten all the way to the Netherlands. There's bears coming back. There's lynx coming back. There's the European jackal. I had no idea such a thing existed. They're coming back from Italy to the rest of Europe. And unlike here, these are all predators, which is kind of interesting. They are being welcomed by Europeans. They've been missed.

CA: And counterintuitively, when you bring back the predators, it actually increases rather than reduces the diversity of the underlying ecosystem often.

SB: Yeah, generally predators and large animals -- large animals and large animals with sharp teeth and claws -- are turning out to be highly important for a really rich ecosystem.

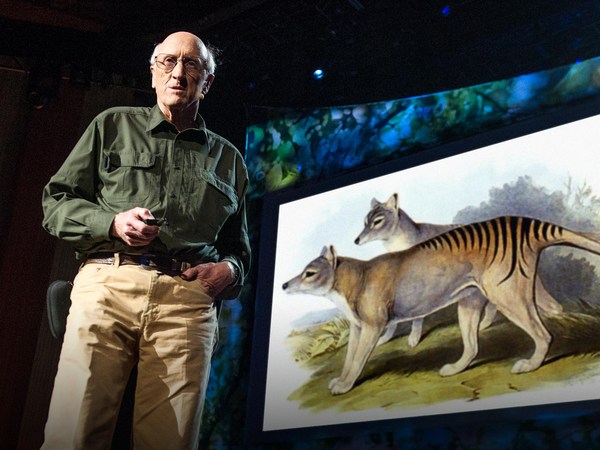

CA: Which maybe brings us to this rather more dramatic rewilding project that you've got yourself involved in. Why would someone want to bring back these terrifying woolly mammoths?

SB: Hmm. Asian elephants are the closest relative to the woolly mammoth, and they're about the same size, genetically very close. They diverged quite recently in evolutionary history. The Asian elephants are closer to woolly mammoths than they are to African elephants, but they're close enough to African elephants that they have successfully hybridized. So we're working with George Church at Harvard, who has already moved the genes for four major traits from the now well-preserved, well-studied genome of the woolly mammoth, thanks to so-called "ancient DNA analysis." And in the lab, he has moved those genes into living Asian elephant cell lines, where they're taking up their proper place thanks to CRISPR. I mean, they're not shooting the genes in like you did with genetic engineering. Now with CRISPR you're editing, basically, one allele, and replacing it in the place of another allele. So you're now getting basically Asian elephant germline cells that are effectively in terms of the traits that you're going for to be comfortable in the Arctic, you're getting them in there.

So we go through the process of getting that through a surrogate mother, an Asian elephant mother. You can get a proxy, as it's being called by conservation biologists, of the woolly mammoth, that is effectively a hairy, curly-trunked, Asian elephant that is perfectly comfortable in the sub-Arctic. Now, it's the case, so many people say, "Well, how are you going to get them there? And Asian elephants, they don't like snow, right?" Well, it turns out, they do like snow. There's some in an Ontario zoo that have made snowballs bigger than people. They just love -- you know, with a trunk, you can start a little thing, roll it and make it bigger. And then people say, "Yeah, but it's 22 months of gestation. This kind of cross-species cloning is tricky business, anyway. Are you going to lose some of the surrogate Asian elephant mothers?" And then George Church says, "That's all right. We'll do an artificial uterus and grow them that way." Then people say, "Yeah, next century, maybe," except the news came out this week in Nature that there's now an artificial uterus in which they've grown a lamb to four weeks. That's halfway through its gestation period. So this stuff is moving right along.

CA: But why should we want a world where -- Picture a world where there are thousands of these things thundering across Siberia. Is that a better world?

SB: Potentially. It's --

(Laughter)

There's three groups, basically, working on the woolly mammoth seriously: Revive & Restore, we're kind of in the middle; George Church and the group at Harvard that are doing the genetics in the lab; and then there's an amazing old scientist named Zimov who works in northern Siberia, and his son Nikita, who has bought into the system, and they are, Sergey and Nikita Zimov have been, for 25 years, creating what they call "Pleistocene Park," which is a place in a really tough part of Siberia that is pure tundra. And the research that's been done shows that there's probably one one-hundredth of the animals on the landscape there that there used to be. Like that earlier image, we saw lots of animals. Now there's almost none. The tundra is mostly moss, and then there's the boreal forest. And that's the way it is, folks. There's just a few animals there.

So they brought in a lot of grazing animals: musk ox, Yakutian horses, they're bringing in some bison, they're bringing in some more now, and put them in at the density that they used to be. And grasslands are made by grazers. So these animals are there, grazing away, and they're doing a couple of things. First of all, they're turning the tundra, the moss, back into grassland. Grassland fixes carbon. Tundra, in a warming world, is thawing and releasing a lot of carbon dioxide and also methane. So already in their little 25 square miles, they're doing a climate stabilization thing. Part of that story, though, is that the boreal forest is very absorbent to sunlight, even in the winter when snow is on the ground. And the way the mammoth steppe, which used to wrap all the way around the North Pole -- there's a lot of landmass around the North Pole -- that was all this grassland. And the steppe was magnificent, probably one of the most productive biomes in the world, the biggest biome in the world. The forest part of it, right now, Sergey Zimov and Nikita go out with this old military tank they got for nothing, and they knock down the trees. And that's a bore, and it's tiresome, and as Sergey says, "... and they make no dung!" which, by the way, these big animals do, including mammoths. So mammoths become what conservation biologists call an umbrella species. It's an exciting animal -- pandas in China or wherever -- that the excitement that goes on of making life good for that animal is making a habitat, an ecosystem, which is good for a whole lot of creatures and plants, and it ideally gets to the point of being self-managing, where the conservation biologists can back off and say, "All we have to do is keep out the destructive invasives, and this thing can just cook."

CA: So there's many other species that you're dreaming of de-extincting at some point, but I think what I'd actually like to move on to is this idea you talked about how mammoths might help green Siberia in a sense, or at least, I'm not talking about tropical rainforest, but this question of greening the planet you've thought about a lot. And the traditional story is that deforestation is one of the most awful curses of modern times, and that it's a huge contributor to climate change. And then you went and sent me this graph here, or this map. What is this map?

SB: Global greening. The thing to do with any narrative that you get from headlines and from short news stories is to look for what else is going on, and look for what Marc Andreessen calls "narrative violation." So the narrative -- and Al Gore is master of putting it out there -- is that there's this civilization-threatening climate change coming on very rapidly. We have to cease all extra production of greenhouse gases, especially CO2, as soon as possible, otherwise, we're in deep, deep trouble. All of that is true, but it's not the whole story, and the whole story is more interesting than these fragmentary stories.

Plants love CO2. What plants are made of is CO2 plus water via sunshine. And so in many greenhouses, industrialized greenhouses, they add CO2 because the plants turn that into plant matter. So the studies have been done with satellites and other things, and what you're seeing here is a graph of, over the last 33 years or so, there's 14 percent more leaf action going on. There's that much more biomass. There's that much more what ecologists call "primary production." There's that much more life happening, thanks to climate change, thanks to all of our goddam coal plants. So -- whoa, what's going on here? By the way, crop production goes up with this. This is a partial counter to the increase of CO2, because there's that much more plant that is sucking it down into plant matter. Some of that then decays and goes right back up, but some of it is going down into roots and going into the soil and staying there. So these counter things are part of what you need to bear in mind, and the deeper story is that thinking about and dealing with and engineering climate is a pretty complex process. It's like medicine. You're always, again, tweaking around with the system to see what makes an improvement. Then you do more of that, see it's still getting better, then -- oop! -- that's enough, back off half a turn.

CA: But might some people say, "Not all green is created equal." Possibly what we're doing is trading off the magnificence of the rainforest and all that diversity for, I don't know, green pond scum or grass or something like that.

SB: In this particular study, it turns out every form of plant is increasing. Now, what's interestingly left out of this study is what the hell is going on in the oceans. Primary production in the oceans, the biota of the oceans, mostly microbial, what they're up to is probably the most important thing. They're the ones that create the atmosphere that we're happily breathing, and they're not part of this study. This is one of the things James Lovelock has been insisting; basically, our knowledge of the oceans, especially of ocean life, is fundamentally vapor, in this sense. So we're in the process of finding out by inadvertent bad geoengineering of too much CO2 in the atmosphere, finding out, what is the ocean doing with that? Well, the ocean, with the extra heat, is swelling up. That's most of where we're getting the sea level rise, and there's a lot more coming with more global warming. We're getting terrible harm to some of the coral reefs, like off of Australia. The great reef there is just a lot of bleaching from overheating. And this is why I and Danny Hillis, in our previous session on the main stage, was saying, "Look, geoengineering is worth experimenting with enough to see that it works, to see if we can buy time in the warming aspect of all of this, tweak the system with small but usable research, and then see if we should do more than tweak.

CA: OK, so this is what we're going to talk about for the last few minutes here because it's such an important discussion. First of all, this book was just published by Yuval Harari. He's basically saying the next evolution of humans is to become as gods. I think he --

SB: Now, you've talked to him. And you've probably finished the book. I haven't finished it yet. Where does he come out on --

CA: I mean, it's a pretty radical view. He thinks that we will completely remake ourselves using data, using bioengineering, to become completely new creatures that have, kind of, superpowers, and that there will be huge inequality. But we're about to write a very radical, brand-new chapter of history. That's what he believes.

SB: Is he nervous about that? I forget.

CA: He's nervous about it, but I think he also likes provoking people.

SB: Are you nervous about that?

CA: I'm nervous about that. But, you know, with so much at TED, I'm excited and nervous. And the optimist in me is trying hard to lean towards "This is awesome and really exciting," while the sort of responsible part of me is saying, "But, uh, maybe we should be a little bit careful as to how we think of it."

SB: That's your secret sauce, isn't it, for TED? Staying nervous and excited.

CA: It's also the recipe for being a little bit schizophrenic. But he didn't quote you. What I thought was an astonishing statement that you made right back in the original Whole Earth Catalog, you ended it with this powerful phrase: "We are as gods, and might as well get good at it." And then more recently, you've upgraded that statement. I want you talk about this philosophy.

SB: Well, one of the things I'm learning is that documentation is better than memory -- by far. And one of the things I've learned from somebody -- I actually got on Twitter. It changed my life -- it hasn't forgiven me yet! And I took ownership of this phrase when somebody quoted it, and somebody else said, "Oh by the way, that isn't what you originally wrote in that first 1968 Whole Earth Catalog. You wrote, 'We are as gods and might as well get used to it.'" I'd forgotten that entirely. The stories -- these goddam stories -- the stories we tell ourselves become lies over time. So, documentation helps cut through that. It did move on to "We are as gods and might as well get good at it," and that was the Whole Earth Catalog. By the time I was doing a book called "Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto," and in light of climate change, basically saying that we are as gods and have to get good at it.

CA: We are as gods and have to get good at it. So talk about that, because the psychological reaction from so many people as soon as you talk about geoengineering is that the last thing they believe is that humans should be gods -- some of them for religious reasons, but most just for humility reasons, that the systems are too complex, we should not be dabbling that way.

SB: Well, this is the Greek narrative about hubris. And once you start getting really sure of yourself, you wind up sleeping with your mother.

(Laughter)

CA: I did not expect you would say that.

(Laughter)

SB: That's the Oedipus story. Hubris is a really important cautionary tale to always have at hand. One of the guidelines I've kept for myself is: every day I ask myself how many things I am dead wrong about. And I'm a scientist by training and getting to work with scientists these days, which is pure joy. Science is organized skepticism. So you're always insisting that even when something looks pretty good, you maintain a full set of not only suspicions about whether it's as good as it looks, but: What else is going on? So this "What else is going?" on query, I think, is how you get away from fake news. It's not necessarily real news, but it's welcomely more complex news that you're trying to take on.

CA: But coming back to the application of this just for the environment: it seems like the philosophy of this is that, whether we like it or not, we are already dominating so many aspects of what happens on planets, and we're doing it unintentionally, so we really should start doing it intentionally. What would it look like to start getting good at being a god? How should we start doing that? Are there small-scale experiments or systems we can nudge and play with? How on earth do we think about it?

SB: The mentor that sort of freed me from total allegiance to Buckminster Fuller was Gregory Bateson. And Gregory Bateson was an epistemologist and anthropologist and biologist and psychologist and many other things, and he looked at how systems basically look at themselves. And that is, I think, part of how you want to always be looking at things. And what I like about David Keith's approach to geoengineering is you don't just haul off and do it. David Keith's approach -- and this is what Danny Hillis was talking about earlier -- is that you do it really, really incrementally, you do some stuff to tweak the system, see how it responds, that tells you something about the system. That's responding to the fact that people say, quite rightly, "What are we talking about here? We don't understand how the climate system works. You can't engineer a system you don't understand." And David says, "Well, that certainly applies to the human body, and yet medicine goes ahead, and we're kind of glad that it has." The way you engineer a system that is so large and complex that you can't completely understand it is you tweak it, and this is kind of an anti-hubristic approach. This is: try a little bit here, back the hell off if it's an issue, expand it if it seems to go OK, meanwhile, have other paths going forward. This is the whole argument for diversity and dialogue and all these other things and the things we were hearing about earlier with Sebastian [Thrun].

So the non-hubristic approach is looking for social license, which is a terminology that I think is a good one, of including society enough in these interesting, problematic, deep issues that they get to have a pretty good idea and have people that they trust paying close attention to the sequence of experiments as it's going forward, the public dialogue as it's going forward -- which is more public than ever, which is fantastic -- and you feel your way, you just ooze your way along, and this is the muddle-through approach that has worked pretty well so far. The reason that Sebastian and I are optimistic is we read people like Steven Pinker, "The Better Angels of Our Nature," and so far, so good. Now, that can always change, but you can build a lot on that sense of: things are capable of getting better, figure out the tools that made that happen and apply those further. That's the story.

CA: Stewart, I think on that optimistic note, we're actually going to wrap up. I am in awe of how you always are willing to challenge yourself and other people. I feel like this recipe for never allowing yourself to be too certain is so powerful. I want to learn it more for myself, and it's been very insightful and inspiring, actually, listening to you today. Stewart Brand, thank you so much.

SB: Thank you.

(Applause)