Now, extinction is a different kind of death. It's bigger. We didn't really realize that until 1914, when the last passenger pigeon, a female named Martha, died at the Cincinnati zoo. This had been the most abundant bird in the world that'd been in North America for six million years. Suddenly it wasn't here at all. Flocks that were a mile wide and 400 miles long used to darken the sun. Aldo Leopold said this was a biological storm, a feathered tempest. And indeed it was a keystone species that enriched the entire eastern deciduous forest, from the Mississippi to the Atlantic, from Canada down to the Gulf. But it went from five billion birds to zero in just a couple decades. What happened?

Well, commercial hunting happened. These birds were hunted for meat that was sold by the ton, and it was easy to do because when those big flocks came down to the ground, they were so dense that hundreds of hunters and netters could show up and slaughter them by the tens of thousands. It was the cheapest source of protein in America. By the end of the century, there was nothing left but these beautiful skins in museum specimen drawers.

There's an upside to the story. This made people realize that the same thing was about to happen to the American bison, and so these birds saved the buffalos.

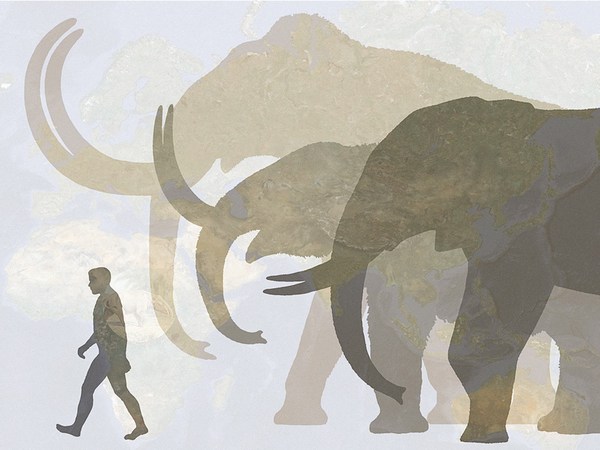

But a lot of other animals weren't saved. The Carolina parakeet was a parrot that lit up backyards everywhere. It was hunted to death for its feathers. There was a bird that people liked on the East Coast called the heath hen. It was loved. They tried to protect it. It died anyway. A local newspaper spelled out, "There is no survivor, there is no future, there is no life to be recreated in this form ever again." There's a sense of deep tragedy that goes with these things, and it happened to lots of birds that people loved. It happened to lots of mammals. Another keystone species is a famous animal called the European aurochs. There was sort of a movie made about it recently. And the aurochs was like the bison. This was an animal that basically kept the forest mixed with grasslands across the entire Europe and Asian continent, from Spain to Korea. The documentation of this animal goes back to the Lascaux cave paintings.

The extinctions still go on. There's an ibex in Spain called the bucardo. It went extinct in 2000. There was a marvelous animal, a marsupial wolf called the thylacine in Tasmania, south of Australia, called the Tasmanian tiger. It was hunted until there were just a few left to die in zoos. A little bit of film was shot.

Sorrow, anger, mourning. Don't mourn. Organize. What if you could find out that, using the DNA in museum specimens, fossils maybe up to 200,000 years old could be used to bring species back, what would you do? Where would you start?

Well, you'd start by finding out if the biotech is really there. I started with my wife, Ryan Phelan, who ran a biotech business called DNA Direct, and through her, one of her colleagues, George Church, one of the leading genetic engineers who turned out to be also obsessed with passenger pigeons and a lot of confidence that methodologies he was working on might actually do the deed.

So he and Ryan organized and hosted a meeting at the Wyss Institute in Harvard bringing together specialists on passenger pigeons, conservation ornithologists, bioethicists, and fortunately passenger pigeon DNA had already been sequenced by a molecular biologist named Beth Shapiro. All she needed from those specimens at the Smithsonian was a little bit of toe pad tissue, because down in there is what is called ancient DNA. It's DNA which is pretty badly fragmented, but with good techniques now, you can basically reassemble the whole genome.

Then the question is, can you reassemble, with that genome, the whole bird? George Church thinks you can. So in his book, "Regenesis," which I recommend, he has a chapter on the science of bringing back extinct species, and he has a machine called the Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering machine. It's kind of like an evolution machine. You try combinations of genes that you write at the cell level and then in organs on a chip, and the ones that win, that you can then put into a living organism. It'll work. The precision of this, one of George's famous unreadable slides, nevertheless points out that there's a level of precision here right down to the individual base pair. The passenger pigeon has 1.3 billion base pairs in its genome.

So what you're getting is the capability now of replacing one gene with another variation of that gene. It's called an allele. Well that's what happens in normal hybridization anyway. So this is a form of synthetic hybridization of the genome of an extinct species with the genome of its closest living relative. Now along the way, George points out that his technology, the technology of synthetic biology, is currently accelerating at four times the rate of Moore's Law. It's been doing that since 2005, and it's likely to continue.

Okay, the closest living relative of the passenger pigeon is the band-tailed pigeon. They're abundant. There's some around here. Genetically, the band-tailed pigeon already is mostly living passenger pigeon. There's just some bits that are band-tailed pigeon. If you replace those bits with passenger pigeon bits, you've got the extinct bird back, cooing at you.

Now, there's work to do. You have to figure out exactly what genes matter. So there's genes for the short tail in the band-tailed pigeon, genes for the long tail in the passenger pigeon, and so on with the red eye, peach-colored breast, flocking, and so on. Add them all up and the result won't be perfect. But it should be be perfect enough, because nature doesn't do perfect either.

So this meeting in Boston led to three things.

First off, Ryan and I decided to create a nonprofit called Revive and Restore that would push de-extinction generally and try to have it go in a responsible way, and we would push ahead with the passenger pigeon.

Another direct result was a young grad student named Ben Novak, who had been obsessed with passenger pigeons since he was 14 and had also learned how to work with ancient DNA, himself sequenced the passenger pigeon, using money from his family and friends. We hired him full-time. Now, this photograph I took of him last year at the Smithsonian, he's looking down at Martha, the last passenger pigeon alive. So if he's successful, she won't be the last.

The third result of the Boston meeting was the realization that there are scientists all over the world working on various forms of de-extinction, but they'd never met each other. And National Geographic got interested because National Geographic has the theory that the last century, discovery was basically finding things, and in this century, discovery is basically making things. De-extinction falls in that category. So they hosted and funded this meeting. And 35 scientists, they were conservation biologists and molecular biologists, basically meeting to see if they had work to do together. Some of these conservation biologists are pretty radical. There's three of them who are not just re-creating ancient species, they're recreating extinct ecosystems in northern Siberia, in the Netherlands, and in Hawaii.

Henri, from the Netherlands, with a Dutch last name I won't try to pronounce, is working on the aurochs. The aurochs is the ancestor of all domestic cattle, and so basically its genome is alive, it's just unevenly distributed. So what they're doing is working with seven breeds of primitive, hardy-looking cattle like that Maremmana primitivo on the top there to rebuild, over time, with selective back-breeding, the aurochs. Now, re-wilding is moving faster in Korea than it is in America, and so the plan is, with these re-wilded areas all over Europe, they will introduce the aurochs to do its old job, its old ecological role, of clearing the somewhat barren, closed-canopy forest so that it has these biodiverse meadows in it.

Another amazing story came from Alberto Fernández-Arias. Alberto worked with the bucardo in Spain. The last bucardo was a female named Celia who was still alive, but then they captured her, they got a little bit of tissue from her ear, they cryopreserved it in liquid nitrogen, released her back into the wild, but a few months later, she was found dead under a fallen tree. They took the DNA from that ear, they planted it as a cloned egg in a goat, the pregnancy came to term, and a live baby bucardo was born. It was the first de-extinction in history.

(Applause)

It was short-lived. Sometimes interspecies clones have respiration problems. This one had a malformed lung and died after 10 minutes, but Alberto was confident that cloning has moved along well since then, and this will move ahead, and eventually there will be a population of bucardos back in the mountains in northern Spain.

Cryopreservation pioneer of great depth is Oliver Ryder. At the San Diego zoo, his frozen zoo has collected the tissues from over 1,000 species over the last 35 years. Now, when it's frozen that deep, minus 196 degrees Celsius, the cells are intact and the DNA is intact. They're basically viable cells, so someone like Bob Lanza at Advanced Cell Technology took some of that tissue from an endangered animal called the Javan banteng, put it in a cow, the cow went to term, and what was born was a live, healthy baby Javan banteng, who thrived and is still alive.

The most exciting thing for Bob Lanza is the ability now to take any kind of cell with induced pluripotent stem cells and turn it into germ cells, like sperm and eggs.

So now we go to Mike McGrew who is a scientist at Roslin Institute in Scotland, and Mike's doing miracles with birds. So he'll take, say, falcon skin cells, fibroblast, turn it into induced pluripotent stem cells. Since it's so pluripotent, it can become germ plasm. He then has a way to put the germ plasm into the embryo of a chicken egg so that that chicken will have, basically, the gonads of a falcon. You get a male and a female each of those, and out of them comes falcons. (Laughter) Real falcons out of slightly doctored chickens.

Ben Novak was the youngest scientist at the meeting. He showed how all of this can be put together. The sequence of events: he'll put together the genomes of the band-tailed pigeon and the passenger pigeon, he'll take the techniques of George Church and get passenger pigeon DNA, the techniques of Robert Lanza and Michael McGrew, get that DNA into chicken gonads, and out of the chicken gonads get passenger pigeon eggs, squabs, and now you're getting a population of passenger pigeons.

It does raise the question of, they're not going to have passenger pigeon parents to teach them how to be a passenger pigeon. So what do you do about that? Well birds are pretty hard-wired, as it happens, so most of that is already in their DNA, but to supplement it, part of Ben's idea is to use homing pigeons to help train the young passenger pigeons how to flock and how to find their way to their old nesting grounds and feeding grounds.

There were some conservationists, really famous conservationists like Stanley Temple, who is one of the founders of conservation biology, and Kate Jones from the IUCN, which does the Red List. They're excited about all this, but they're also concerned that it might be competitive with the extremely important efforts to protect endangered species that are still alive, that haven't gone extinct yet. You see, you want to work on protecting the animals out there. You want to work on getting the market for ivory in Asia down so you're not using 25,000 elephants a year.

But at the same time, conservation biologists are realizing that bad news bums people out. And so the Red List is really important, keep track of what's endangered and critically endangered, and so on. But they're about to create what they call a Green List, and the Green List will have species that are doing fine, thank you, species that were endangered, like the bald eagle, but they're much better off now, thanks to everybody's good work, and protected areas around the world that are very, very well managed. So basically, they're learning how to build on good news. And they see reviving extinct species as the kind of good news you might be able to build on.

Here's a couple related examples. Captive breeding will be a major part of bringing back these species. The California condor was down to 22 birds in 1987. Everybody thought is was finished. Thanks to captive breeding at the San Diego Zoo, there's 405 of them now, 226 are out in the wild. That technology will be used on de-extincted animals. Another success story is the mountain gorilla in Central Africa. In 1981, Dian Fossey was sure they were going extinct. There were just 254 left. Now there are 880. They're increasing in population by three percent a year. The secret is, they have an eco-tourism program, which is absolutely brilliant. So this photograph was taken last month by Ryan with an iPhone. That's how comfortable these wild gorillas are with visitors.

Another interesting project, though it's going to need some help, is the northern white rhinoceros. There's no breeding pairs left. But this is the kind of thing that a wide variety of DNA for this animal is available in the frozen zoo. A bit of cloning, you can get them back.

So where do we go from here? These have been private meetings so far. I think it's time for the subject to go public. What do people think about it? You know, do you want extinct species back? Do you want extinct species back?

(Applause)

Tinker Bell is going to come fluttering down. It is a Tinker Bell moment, because what are people excited about with this? What are they concerned about?

We're also going to push ahead with the passenger pigeon. So Ben Novak, even as we speak, is joining the group that Beth Shapiro has at UC Santa Cruz. They're going to work on the genomes of the passenger pigeon and the band-tailed pigeon. As that data matures, they'll send it to George Church, who will work his magic, get passenger pigeon DNA out of that. We'll get help from Bob Lanza and Mike McGrew to get that into germ plasm that can go into chickens that can produce passenger pigeon squabs that can be raised by band-tailed pigeon parents, and then from then on, it's passenger pigeons all the way, maybe for the next six million years. You can do the same thing, as the costs come down, for the Carolina parakeet, for the great auk, for the heath hen, for the ivory-billed woodpecker, for the Eskimo curlew, for the Caribbean monk seal, for the woolly mammoth.

Because the fact is, humans have made a huge hole in nature in the last 10,000 years. We have the ability now, and maybe the moral obligation, to repair some of the damage. Most of that we'll do by expanding and protecting wildlands, by expanding and protecting the populations of endangered species. But some species that we killed off totally we could consider bringing back to a world that misses them.

Thank you.

(Applause)

Chris Anderson: Thank you. I've got a question. So, this is an emotional topic. Some people stand. I suspect there are some people out there sitting, kind of asking tormented questions, almost, about, well, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait a minute, there's something wrong with mankind interfering in nature in this way. There's going to be unintended consequences. You're going to uncork some sort of Pandora's box of who-knows-what. Do they have a point?

Stewart Brand: Well, the earlier point is we interfered in a big way by making these animals go extinct, and many of them were keystone species, and we changed the whole ecosystem they were in by letting them go. Now, there's the shifting baseline problem, which is, so when these things come back, they might replace some birds that are there that people really know and love. I think that's, you know, part of how it'll work. This is a long, slow process -- One of the things I like about it, it's multi-generation. We will get woolly mammoths back.

CA: Well it feels like both the conversation and the potential here are pretty thrilling. Thank you so much for presenting. SB: Thank you.

CA: Thank you. (Applause)