In 1624, Mughal Emperor Jahangir received word of yet another defeat at the hands of his greatest enemy: Malik Ambar. Despite coming to India as an enslaved youth, Ambar had risen to rule over the Indian Sultanate of Ahmednagar. And his brilliant military tactics had brought the Mughals’ march of conquest to a screeching halt. Jahangir was so obsessed with defeating his rival, he'd commissioned a painting of himself shooting an arrow at Ambar's skull.

Malik Ambar was born in the late 1540s in central Ethiopia as Chapu, a member of the Oromo people. Every year, as part of ongoing conflicts with their neighbors, Oromo youth were among the thousands of Ethiopians captured and sold into the Indian Ocean Slave Trade. In this part of the world, enslaved individuals retained some legal rights and enslavers could be held accountable for severe mistreatment. There was also less legal discrimination against previously enslaved people, allowing some individuals who gained their freedom to acquire great wealth and power. However, these circumstances shouldn’t overshadow the trauma of enslavement, which violently severed individuals from their lives and loved ones.

Around the age of 12, Chapu was among those taken into bondage. Captives were typically shipped to the Middle East or South Asia. Women were sold into sexual slavery as concubines or forced to become domestic servants, a position in which they often had to endure harassment and sexual violence. Men were either purchased for dangerous physical labor or by wealthy individuals who trained them to become servants of the political and military elite.

Chapu was part of the latter group. He was taken to Baghdad, where he was educated in Arabic among other subjects and converted to Islam before being resold to the chief minister of Ahmednagar. The minister himself was a formerly enslaved African, but after being freed, he’d risen through the ranks, becoming second in command to the sultan himself. Chapu— now known as Malik Ambar— became the chief minister’s protégé, observing him advise the sultan, enact policies, and navigate court politics. After the minister’s death, his widow granted Ambar’s freedom, and like many newly freed Africans in India at the time, Ambar became a mercenary soldier.

Ahmednagar was frequently under attack from Mughal invaders, who were determined to expand their empire. But Ambar’s daring guerrilla tactics derailed the invaders’ plans by interrupting Mughal supply lines.

Ambar’s military success earned him a following, and in 1600, he used his influence to take advantage of a royal power vacuum. After placing a young puppet ruler on the throne, Ambar became the regent and new chief minister. He also married his daughter to the new sultan, creating a direct tie to the royal family. Not all parties were pleased with Ambar's power grab, and the new sultan eventually conspired to remove Ambar from power. But before these plans could take form, both conspirators were mysteriously poisoned. The sultan’s five-year-old son was then placed on the throne, giving Malik Ambar, a once enslaved ex-soldier, complete political, economic, and military control over Ahmednagar.

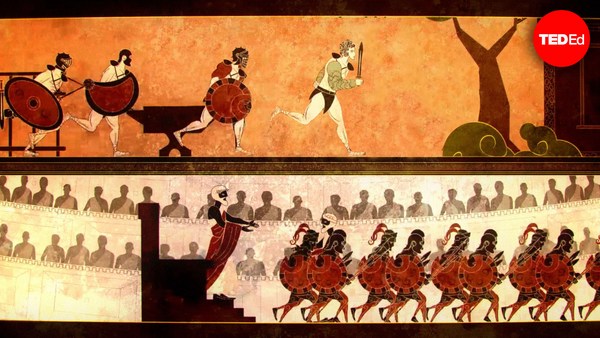

Ambar remained in power for over 25 years, bringing long-term stability to the embattled region. He built a new capital city, negotiated trade deals with Indian and European merchants, and reformed the tax system to better protect peasants. But most importantly, he continued to foil the Mughal invasion. His ragtag army of local Indians, enslaved and newly freed Africans was religiously and ethnically diverse, yet they were united by Ambar’s leadership. And he made up for his lack of numbers by launching lightning attacks that demoralized and exhausted the Mughal troops long before they reached the battlefield.

Jealous of Ambar’s success and popularity, some of his enemies accused him of maintaining power through sorcery and devil worship. Others begrudgingly acknowledged his piety, generosity, and military genius. Regardless, very few ever outmaneuvered him. Malik Ambar died of natural causes in 1626, leaving Ahmednagar to his son, who was unable to maintain his father’s military record. Just seven years later, the sultanate finally fell to the Mughal forces— heralding the fall of the kingdom Ambar had risen to lead.