As the warrior slept, a snake coiled around his face. Instead of a threat, his wife saw an omen– a fearsome power that would lead her husband to either glory or doom. For now, however, he was only a slave – one of millions taken from the territories conquered by Rome to work the mines, till the fields, or fight for the crowd’s entertainment. A nomadic Thracian from what is now Bulgaria, he had served in the Roman Army but was imprisoned for desertion. His name was Spartacus.

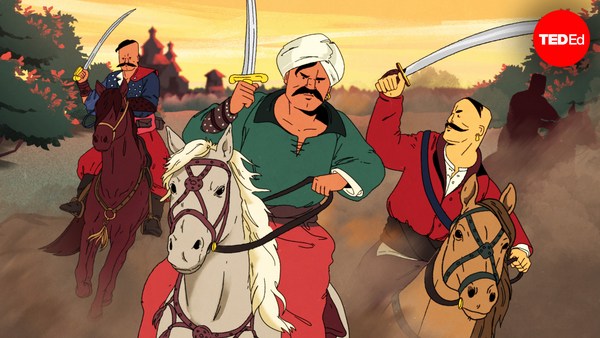

Spartacus had been brought to Capua by Batiatus, a lanista, or trainer of gladiators. And life at the ludus, or gladiator school, was unforgiving. New recruits were forced to swear an oath “to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword,” and to obey their master’s will without question. But even harsh discipline couldn’t break Spartacus’s spirit. In 73 BCE, Spartacus led 73 other slaves to seize knives and skewers from the kitchen and fight their way out, hijacking a wagon of gladiator equipment along the way. They were done fighting for others– now, they fought for their freedom.

When the news reached Rome, the Senate was too busy with wars in Spain and the Pontic Empire to worry about some unruly slaves. Unconcerned, praetor Claudius Glaber took an army of three thousand men to the rebel’s refuge at Mount Vesuvius, and blocked off the only passage up the mountain. All that remained was to wait and starve them out– or so he thought. In the dead of night, the rebels lowered themselves down the cliffside on ropes made from vines, and flanked Glaber’s unguarded camp. Thus began the legend of Rome’s defiant gladiator.

As news of the rebellion spread, its ranks swelled with escaped slaves, deserting soldiers, and hungry peasants. Many were untrained, but Spartacus’s clever tactics transformed them into an effective guerrilla force. A second Roman expedition led by praetor Varinius, was ambushed while the officer bathed. To elude the remaining Roman forces, the rebels used their enemy’s corpses as decoy guards, stealing Varinius’s own horse to aid their escape.

Thanks to his inspiring victories and policy of distributing spoils equally, Spartacus continued attracting followers, and gained control of villages where new weapons could be forged. The Romans soon realized they were no longer facing ragtag fugitives, and in the spring of 72 BCE, the Senate retaliated with the full force of two legions. The rebels left victorious, but many lives were lost in the battle, including Spartacus’ lieutenant Crixus. To honor him, Spartacus held funeral games, forcing his Roman prisoners to play the role his fellow rebels had once endured.

By the end of 72 BCE, Spartacus’ army was a massive force of roughly 120,000 members. But those numbers proved difficult to manage. With the path to the Alps clear, Spartacus wanted to march beyond Rome’s borders, where his followers would be free. But his vast army had grown brash. Many wanted to continue pillaging, while others dreamed of marching on Rome itself. In the end, the rebel army turned south– forgoing what would be their last chance at freedom.

Meanwhile, Marcus Licinius Crassus had assumed control of the war. As Rome’s wealthiest citizen, he pursued Spartacus with eight new legions, eventually trapping the rebels in the toe of Italy. After failed attempts to build rafts, and a stinging betrayal by local pirates, the rebels made a desperate run to break through Crassus’s lines– but it was no use. Roman reinforcements were returning from the Pontic wars, and the rebels’ ranks and spirits were broken. In 71 BCE, they made their last stand. Spartacus nearly managed to reach Crassus before being cut down by centurions. His army was destroyed, and 6000 captives were crucified along the Appian Way– a haunting demonstration of Roman authority.

Crassus won the war, but it is not his legacy which echoes through the centuries. Thousands of years later, the name of the slave who made the world’s mightiest empire tremble has become synonymous with freedom– and the courage to fight for it.