Medieval Europe. Where unbathed, sword-wielding knights ate rotten meat, thought the Earth was flat, defended chastity-belt wearing maidens, and tortured their foes with grisly gadgets. Except... this is more fiction than fact. So, where do all the myths about the Middle Ages come from? And what were they actually like?

The “Middle Ages” refers to a 1,000-year timespan, stretching from the fall of Rome in the 5th century to the Italian renaissance in the 15th. Though it’s been applied to other parts of the world, the term traditionally refers specifically to Europe.

One misconception is that medieval people were all ignorant and uneducated. For example, a 19th century biography of Christopher Columbus incorrectly purported that medieval Europeans thought the Earth was flat. Sure, many medieval scholars describe the Earth as the center of the universe— but there wasn't much debate as to its shape. A popular 13th century text was literally called “On the Sphere of the World.” And literacy rates gradually increased during the Middle Ages alongside the establishment of monasteries, convents and universities. Ancient knowledge was also not “lost”; Greek and Roman texts continued to be studied.

The idea that medieval people ate rotten meat and used spices to cover the taste was popularized in the 1930s by a British book. It misinterpreted one medieval recipe and used the existence of laws barring the sale of putrid meat as evidence it was regularly consumed. In fact, medieval Europeans avoided rancid foods and had methods for safely preserving meats, like curing them with salt. Spices were popular. But they were oftentimes pricier than meat itself. So if someone could afford them, they could also buy unspoiled food.

Meanwhile, the 19th century French historian Jules Michelet referred to the Middle Ages as “a thousand years without a bath.” But even small towns boasted well-used public bathhouses. People lathered up with soaps made of things like animal fat, ash, and scented herbs. And they used mouthwash, teeth-scrubbing cloths with pastes and powders, and spices and herbs for fresh-smelling breath.

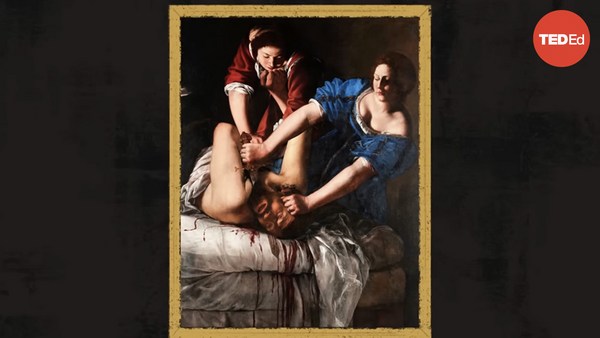

So, how about medieval torture devices? In the 1890s, a collection of allegedly “terrible relics of a semi-barbarous age” went on tour. Among them: the Iron Maiden, which fascinated viewers with its spiked doors— but it was fabricated, possibly just decades before. And there’s no indication Iron Maidens actually existed in the Middle Ages. The “Pear of Anguish,” meanwhile, did exist— but probably later on and it couldn’t have been used for torture. It may have just been a shoe-stretcher. Indeed, many ostensibly medieval torture devices are far more recent inventions. Medieval legal proceedings were overall less gruesome than these gadgets suggest. They included fines, imprisonment, public humiliation, and certain forms of corporal punishment. Torture and executions did happen, but especially violent punishments, like drawing and quartering, were generally reserved for crimes like high treason.

Surely chastity belts were real, though, right? Probably not. They were first mentioned by a 15th century German engineer, likely in jest, alongside fart jokes and a device for invisibility. From there, they became popular subjects of satire that were later mistaken for medieval reality.

Ideas about the Middle Ages have varied depending on the interest of those in later times. The term— along with the pejorative “Dark Ages”— was popularized during the 15th and 16th centuries by scholars biased toward the Classical and Modern periods that came before and after. And, as Enlightenment thinkers celebrated their dedication to reason, they depicted medieval people as superstitious and irrational. In the 19th century, some Romantic European nationalist thinkers— well— romanticized the Middle Ages. They described isolated, white, Christian societies, emphasizing narratives of chivalry and wonder. But knights played minimal roles in medieval warfare. And the Middle Ages saw large-scale interactions. Ideas flowed into Europe along Byzantine, Muslim, and Mongol trade routes. And merchants, intellectuals, and diplomats of diverse origins visited medieval European cities.

The biggest myth may be that the millennium of the Middle Ages amounts to one distinct, cohesive period of European history at all. Originally defined less by what they were than what they weren’t, the Middle Ages became a ground for dueling ideas— fueling more fantasy than fact.