A woman enters an enemy army camp. When the watchmen stop her, she says she’s willing to tell her people’s secrets to the ranking general.

But she isn’t actually a traitor. On her fourth day under the general’s protection, she waits for him to get drunk and beheads him, saving her people from his tyranny.

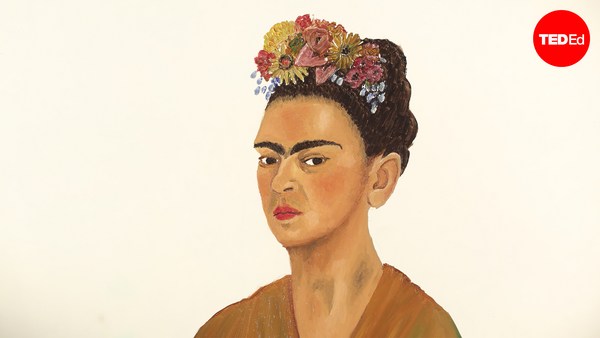

This is the biblical story of how the heroine Judith slays the brutal Holofernes. It features in countless works of art, including the Sistine Chapel. But the most iconic depiction of all was painted by an artist who tackled this ambitious scene when she was just 19 years old. Her name was Artemisia Gentileschi, though many scholars refer to her simply as Artemisia, like other Italian masters. So who was Artemisia, and what sets her depiction apart from the rest?

Artemisia received her artistic training from her father Orazio Gentileschi. He tutored her in the dramatic new style of painting pioneered by the artist Caravaggio. This style, called the Baroque, built upon earlier Renaissance traditions.

While Renaissance artists had focused on imitating the classical Greeks, depicting moments of calmness or poise amidst intensity, Baroque artists emphasized the climactic moment of a story with dynamic action. Baroque works also dial up the drama through composition and extreme contrasts of light and dark, called chiaroscuro or tenebrism. Taken together, the effect is a more direct emotional appeal to viewers.

Though Artemisia drew from Caravaggio’s style, by many accounts, her rendering outmatched the older master’s depiction of the same story. Like Artemisia, Caravaggio focused on the moment of the beheading, dramatically contrasting light and dark and emphasizing the gore. But his painting lacks the visceral impact of Artemisia’s. Where Caravaggio’s heroine keeps her distance from the bloody act, Artemisia’s Judith pushed up her sleeves and wedged her knee on the bed to counter Holofernes’ resistance. Her body has a heft that makes the action believable, and the viscous streams of blood soaking the sheets are highly naturalistic. The blood spraying from the severed artery in Caravaggio’s looks stilted and artificial by comparison.

And yet this isn't even her most celebrated painting of the scene. She finished this painting in 1613, shortly after marrying and moving to Florence, where she found professional success following a very difficult period in her life. In 1611, a colleague of her father’s, Agostino Tassi, nicknamed “lo Smargiasso,” or “the bully,” raped her. When Artemisia told her father, he filed charges for the crime of “forcible violation of a virgin”— a designation that meant Tassi had damaged Orazio’s property. Rape laws centered almost entirely on young women's bodies as commodities owned by their fathers. Tassi’s trial lasted for seven months, during which Artemisia was subjected to interrogation and torture with thumbscrews as she testified against him. Tassi was ultimately found guilty, but his powerful patrons managed to have his sentence revoked.

Some scholars have suggested that Artemisia started the painting while the trial was still underway. Many have debated whether the rape influenced her work.

Artemisia revisited the subject of Judith repeatedly. One painting shows Judith and her maidservant trying to leave the enemy encampment. Here, Artemisia added a tiny ornament in Judith’s hair, possibly referencing David, the protector of Florence, with a nod to Michelangelo. On the sword’s hilt there’s a screaming Gorgon or Medusa— both female archetypes evoking rage and power which link the work to Caravaggio.

Artemisia painted her most famous portrayal of Judith between 1618 and 1620. The composition is similar to that of her first painting from 1613, but has meaningful details for those who look closely. The sword more directly resembles a crucifix, heightening the sense that Judith's vengeance was a holy act ordained by God. Artemisia also added a bracelet featuring the goddess of the hunt— her namesake, Artemis. This signature is one of the many ways her art holds true to a sentiment that she expressed near the end of her life: “The works will speak for themselves.”