I'm an industrial designer, which means I create all these cool things from ideas that we surround ourselves with, or in this case, geeky people surround themselves with, for the most part. I have absolutely no background in biology, chemistry or engineering, so bear with me, because I'll be talking about biomedical engineering today.

(Laughter)

And please do stay here in the meantime.

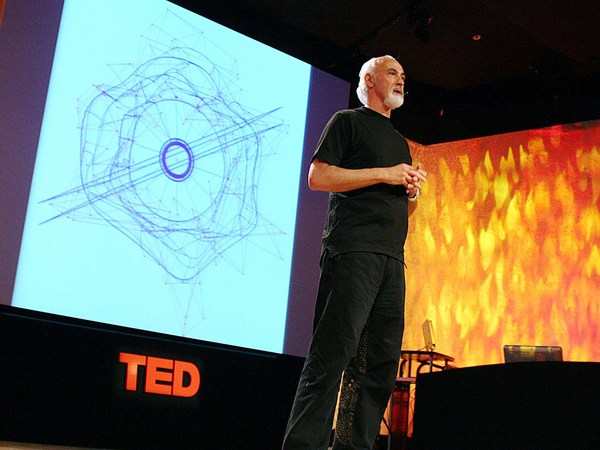

Industrial design is about making lots of things identical. The downside about that is, there's something impersonal about lots of identical things, because when you're trying to design one thing for one person to solve one issue, you can't really do that when you're making things aimed more to a demographic model or to a marketing requirements document, which is what we live by. So I got disheartened by the whole process in general, and went to rethink it and redesign designing altogether, went way back to my early, early design inspirations, and back to about eight years old, and that got me to this guy. Anyone here from MIT knows him or has a tattoo or poster of him somewhere.

(Laughter)

Anyone else in the room, just for a hint, he is the engineer of engineers or the designer of designers. He is the guy who made bionics a household word in the form of the polyester-clad Six Million Dollar Man that I grew up with.

The thing that came from this pop culture show, the real takeaway, was two main things: if you're designing for the person, for a real person, you don't settle for the minimum functional requirements; you see how far beyond that you can go, where the rewards really are way out in the fringe of how far past that document you can go. And if you can nail that, you stand to improve the quality of life for somebody for every moment for the rest of their life. I kind of distilled that down into a design philosophy, and infuse that into the studio that I have now; I'm trying to get everyone to think along these lines. It's not a profound philosophy, but it works for us.

We work with prosthetic limbs, and the first thing you see about prosthetic limbs is that they are engineering brilliance. They can do amazing things; they can return all kinds of functionality and performance back to somebody's life. But from the vantage of an industrial designer, they're not quite there. What we don't see is the sculpture or the beauty or the individual qualities or the uniqueness or the elegance to them. They are brilliant, mechanical, utilitarian devices. And that's great, except for a lot of people, that doesn't work. People come to our studio all the time, and they have bubble wrap and duct tape, trying to approximate their original form. Or they'll have a gym sock stuffed with other gym socks to try to recreate the shape that once was; and that, to us, is not thriving.

The body, to us, is not a mechanical entity, where mechanical-only solutions can address them. It's our personal sculpture, our kinematic sculpture. It is our canvas; it represents not just our physicality, but also a lot of our personality as well. So when you're designing for the body, maybe the thing isn't to design for mass production, but to design with the body in mind, to really think about curves instead of hard geometry, or uniqueness instead of identical. The problem is, we're constrained by mass production, which makes a million identical things but can't make one unique, individualized thing. So we scrapped that in the new design process, and we start with the person.

This is a three-dimensional scanner, and that's what happens when you scan somebody: you get three-dimensional data into your computer. You can take the sound-side limb there, the surviving limb, mirror it over, and from now on, anything in the process will recreate symmetry -- something as personal and as hard to achieve as symmetry in the body. And you create a product that, no matter what, it's going to be as unique as their fingerprint. In fact, our process is incapable of creating two identical things. So we run it through computer modeling, 3D CAD. Here, we actually infuse a lot of the individual's taste and personality into it, everywhere we can, and we three-dimensionally print the results. We call the resulting parts "fairings," because they're named after the panels on a motorcycle that turn it from a mechanical thing into a sculptural thing.

We tried this on Chad. Chad is a competitive soccer player, lost his leg eight years ago to cancer. You can imagine, it's really tricky to play soccer when you have titanium pipe where there used to be a leg. The resulting parts recreated his shape and deliberately had an aesthetic that look like sporting gear. We wanted it to make it look like he just pulled it out of the gym bag, so it's fairly utilitarian in that regard. Two things happened. One, we expected: his sense of his body came back to him. He was suddenly able to control the ball, to feel the ball, because his body remembered that original shape that he had had up until eight years ago. The other thing, though, is that the other members of the team stopped thinking of him as the amputee on the team. Not that they didn't know, but it stopped becoming a focal point for him. And there is a certain very quiet value in that, we like to believe.

James lost his leg in a motorcycle crash. And the motorcycle is still a big part of James's personality and style. Check out the tattoo on his forearm. We three-dimensionally printed that into what would be his calf. He has his tattoo, he has his morphology and he has the materials of his motorcycle. And the result is interesting in that you can't really tell at first glance where the motorcycle stops and where James starts. It's kind of a chimera hybrid between the two, and James likes that.

(Laughter)

So, we don't ever try to make something look like it could be human. Our whole goal is to be unapologetically man-made, to take what's already there, morphology, and just make it really cool and beautiful, something that somebody can't wait to show the world, because that changes their look. You don't look at him and say, "He's an amputee with a prosthetic." You say, "He's a guy with something really cool going on.

Deborah wanted her curves back, but she also just wanted what came out of it to be really sexy, which is great for us to hear. We created this lace pattern that lends itself well to 3D printing. We created the first leg, I think, where the lace defines the contour of the leg, instead of the leg giving form to the lace. We switched things over. What I like about this shot is you can see daylight through it. So we're not trying to hide anything; the load-bearing carbon component is totally visible. We're just giving it form and shape and contours that were hers to begin with. We made her another leg that matched her purse, just because we could.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

We made another one where we laser-tattooed the leather, because how cool would it be to be able to change your tattoos out from one minute to the next? Love that. We try to capture as much of somebody's personality as we can.

This is George. His will be finished next week. This is the raw computer data that we deal with. He's kind of a classic, timeless-type personality, so we did herringbone tweed, but in polished nickel.

(Laughter)

And Uve was all too proud to show his tattoos, so we are laser-tattooing those into the leather. Part of it is, yes, we're showing off, because we can do this, but the other part is this connects him to what will be a part of him. That is something really valuable; we believe in that. Tattoos are especially exciting for us. What happens if you take the tattoo, which is a combination of somebody's personal taste and choice, and their morphology, but now, let's say, you remove the person. You get a free-floating tattoo defining their body. So everything we do is about recreating and expressing something that means something to that person, and expressing that through what would be their body, whether it's speed or attitude or bling, whatever it is that captures and suggests them in the best way we can.

Back to the 3D-printing thing and this whole process: we have a process that lends itself to making one thing per person; it's very individual, and it actually really lends itself well to complexity. So why not just print the entire leg? That's the concept that preceded the work we're doing now. This is a three-dimensionally printed leg. It's symmetric to the other leg. It is made in America, it is a trivially low-carbon footprint to create, curbside recyclable, costs about 4,000 dollars to create, and it is dishwasher-safe.

(Laughter)

There's a value to that, too. People don't think about that all the time, but yes, throw it in the dishwasher, it works just great. This was based on the original idea that I could go anywhere in the world with nothing more than a camera and a laptop computer, use the camera as a 3D scanner and create for somebody, in a matter of hours, a very high-quality, three-dimensionally printed leg for a very low cost. The proof of concept works great, we're finding it; we'll get there. Or, we upped the quality of the materials and created this for John. The fun thing with John's leg is that when his fiancee looked at this, she joked and said, "I like that leg better than that leg."

(Laughter)

And it's a joke -- she knows full well what he goes through -- but at the same time, there's something very valuable. He turned to us and said, "Nobody says that." He's never heard that in his life. That connected with him very deeply.

So we like to think that this is a new type of design, where you're turning the original process on its head, where there is a dialogue that forms between the designer and the end user, where the designer relinquishes some of the control -- designers hate doing that -- and instead, is the curator of a process. And the end user relinquishes their body into the process, and their taste. I'd like to think that speaks to a greater change that's happening in the design world altogether; in this case, it's one where products will be evaluated on how well they address the individual. The individual will actually be part of the DNA of the end product itself. We will be evaluating products on how well they address a unique person, instead of a demographic model.

This all really hit home for us in one of the first legs we did; when Chad here put on the leg, reached down and felt it and thought about it for a while. Then he turned to us and said, "That's the first time I've felt that shape in eight years." We thought about that. And for all the technology and all the nights and energy we put into it, that's all we really wanted to hear.

Thanks.

(Applause)