My name is Lovegrove. I only know nine Lovegroves, two of which are my parents. They are first cousins, and you know what happens when, you know --

(Laughter)

So there's a terribly weird freaky side to me, which I'm fighting with all the time. So to try and get through today, I've kind of disciplined myself with an 18-minute talk. I was hanging on to have a pee. I thought perhaps if I was hanging on long enough, that would guide me through the 18 minutes.

(Laughter)

OK. I am known as Captain Organic and that's a philosophical position as well as an aesthetic position. But today what I'd like to talk to you about is that love of form and how form can touch people's soul and emotion. Not very long ago, not many thousands of years ago, we actually lived in caves, and I don't think we've lost that coding system. We respond so well to form. But I'm interested in creating intelligent form. I'm not interested at all in blobism or any of that superficial rubbish that you see coming out as design. This artificially induced consumerism -- I think it's atrocious.

My world is the world of people like Amory Lovins, Janine Benyus, James Watson. I'm in that world, but I work purely instinctively. I'm not a scientist. I could have been, perhaps, but I work in this world where I trust my instincts. So I am a 21st-century translator of technology into products that we use everyday and relate beautifully and naturally with. And we should be developing things -- we should be developing packaging for ideas which elevate people's perceptions and respect for the things that we dig out of the earth and translate into products for everyday use. So, the water bottle.

I'll begin with this concept of what I call DNA. DNA: Design, Nature, Art. These are the three things that condition my world. Here is a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, 500 years ago, before photography. It shows how observation, curiosity and instinct work to create amazing art. Industrial design is the art form of the 21st century. People like Leonardo -- there have not been many -- had this amazingly instinctive curiosity. I work from a similar position. I don't want to sound pretentious saying that, but this is my drawing made on a digital pad a couple of years ago -- well into the 21st century, 500 years later. It's my impression of water. Impressionism being the most valuable art form on the planet as we know it: 100 million dollars, easily, for a Monet.

I use, now, a whole new process. A few years ago I reinvented my process to keep up with people like Greg Lynn, Thom Mayne, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas -- all these people that I think are persevering and pioneering with fantastic new ideas of how to create form. This is all created digitally. Here you see the machining, the milling of a block of acrylic. This is what I show to the client to say, "That's what I want to do." At that point, I don't know if that's possible at all. It's a seductor, but I just feel in my bones that that's possible.

So we go, we look at the tooling. We look at how that is produced. These are the invisible things that you never see in your life. This is the background noise of industrial design. That is like an Anish Kapoor flowing through a Richard Serra. It is more valuable than the product in my eyes. I don't have one. When I do make some money, I'll have one machined for myself. This is the final product. When they sent it to me, I thought I'd failed. It felt like nothing. It has to feel like nothing. It was when I put the water in that I realized that I'd put a skin on water itself. It's an icon of water itself, and it elevates people's perception of contemporary design. Each bottle is different, meaning the water level will give you a different shape. It's mass individualism from a single product. It fits the hand. It fits arthritic hands. It fits children's hands. It makes the product strong, the tessellation. It's a millefiori of ideas. In the future, they will look like that, because we need to move away from those type of polymers and use that for medical equipment and more important things, perhaps, in life. Biopolymers, these new ideas for materials, will come into play in probably a decade. It doesn't look as cool, does it? But I can live up to that. I don't have a problem with that. I design for that condition, biopolymers. It's the future.

I took this video in Cape Town last year. This is the freaky side coming out. I have this special interest in things like this, which blow my mind. I don't know whether to, you know, drop to my knees, cry; I don't know what I think. But I just know that nature -- nature improves with ever-greater purpose that which once existed, and that strangeness is a consequence of innovative thinking. When I look at these things, they look pretty normal to me. But these things evolved over many years, and what we're trying to do -- I get three weeks to design a telephone. How the hell do I do that, when you get these things that take hundreds of millions of years to evolve? How do you condense that?

It comes back to instinct. I'm not talking about designing telephones that look like that and I'm not looking at designing architecture like that. I'm just interested in natural growth patterns and the beautiful forms that only nature really creates. How that flows through me and how that comes out is what I'm trying to understand.

This is a scan through the human forearm. It's then blown up through rapid prototyping to reveal its cellular structure. I have these in my office. My office is a mixture of the Natural History Museum and a NASA space lab. It's a weird, kind of freaky place. This is one of my specimens.

This is made -- bone is made from a mixture of inorganic minerals and polymers. I studied cooking in school for four years, and in that experience, which was called "domestic science," it was a bit of a cheap trick for me to try and get a science qualification.

(Laughter)

Actually, I put marijuana in everything I cooked --

(Laughter)

And I had access to all the best girls. It was fabulous. All the guys in the rugby team couldn't understand. Anyway -- this is a meringue. This is another sample I have. A meringue is made exactly the same way, in my estimation, as a bone. It's made from polysaccharides and proteins. If you pour water on that, it dissolves. Could we be manufacturing from foodstuffs in the future? Not a bad idea. I don't know. I need to talk to Janine and a few other people about that, but I believe instinctively that that meringue can become something, a car -- I don't know.

I'm also interested in growth patterns: the unbridled way that nature grows things so you're not restricted by form at all. These interrelated forms, they do inspire everything I do, although I might end up making something incredibly simple. This is a detail of a chair that I've designed in magnesium. It shows this interlocution of elements and the beauty of, kind of, engineering and biological thinking, shown pretty much as a bone structure. Any one of those elements you could sort of hang on the wall as some kind of art object.

It's the world's first chair made in magnesium. It cost 1.7 million dollars to develop. It's called "Go," by Bernhardt, USA. It went into Time magazine in 2001 as the new language of the 21st century. Boy. For somebody growing up in Wales in a little village, that's enough. It shows how you make one holistic form, like the car industry, and then you break up what you need. This is an absolutely beautiful way of working. It's a godly way of working. It's organic and it's essential. It's an absolutely fat-free design, and when you look at it, you see human beings.

When that moves into polymers, you can change the elasticity, the fluidity of the form. This is an idea for a gas-injected, one-piece polymer chair. What nature does is it drills holes in things. It liberates form. It takes away anything extraneous. That's what I do. I make organic things which are essential. And they look funky, too -- but I don't set out to make funky things because I think that's an absolute disgrace.

I set out to look at natural forms. If you took the idea of fractal technology further, take a membrane, shrinking it down constantly like nature does -- that could be a seat for a chair. It could be a sole for a sports shoe. It could be a car blending into seats. Wow. Let's go for it. That's the kind of stuff. This is what exists in nature. Observation now allows us to bring that natural process into the design process every day. That's what I do.

This is a show that's currently on in Tokyo. It's called "Superliquidity." It's my sculptural investigation. It's like 21st-century Henry Moore. When you see a Henry Moore, still, your hair stands up. There's some amazing spiritual connect. If he was a car designer, phew, we'd all be driving one. In his day, he was the highest taxpayer in Britain.

That is the power of organic design. It contributes immensely to our -- sense of being, our sense of relationships with things, our sensuality and, you know, the sort of -- even the sort of socio-erotic side, which is very important. This is my artwork. This is all my process. These actually are sold as artwork. They're very big prints. But this is how I get to that object.

Ironically, that object was made by the Killarney process, which is a brand-new process here for the 21st century, and I can hear Greg Lynn laughing his socks off as I say that. I'll tell you about that later.

When I look into these data images, I see new things. It's self-inspired. Diatomic structures, radiolaria, the things that we couldn't see but we can do now -- these, again, are cored out. They're made virtually from nothing. They're made from silica. Why not structures from cars like that? Coral, all these natural forces, take away what they don't need and they deliver maximum beauty. We need to be in that realm. I want to do stuff like that.

This is a new chair which should come on the market in September. It's for a company called Moroso in Italy. It's a gas-injected polymer chair. Those holes you see there are very filtered-down, watered-down versions of the extremity of the diatomic structures. It goes with the flow of the polymer and you'll see -- there's an image coming up right now that shows the full thing. It's great to have companies in Italy who support this way of dreaming. If you see the shadows that come through that, they're actually probably more important than the product, but it's the minimum it takes. The coring out of the back lets you breathe. It takes away any material you don't need and it actually garners flexure too.

I was going to break into a dance then.

This is some current work I'm doing. I'm looking at single-surface structures and how they stretch and flow. It's based on furniture typologies, but that's not the end motivation. It's made from aluminum ... as opposed to aluminium, and it's grown. It's grown in my mind, and then it's grown in terms of the whole process that I go through.

This is two weeks ago in CCP in Coventry, who build parts for Bentleys and so on. It's being built as we speak and it will be on show in Phillips next year in New York. I have a big show with Phillips Auctioneers. When I see these animations, oh Jesus, I'm blown away. This is what goes on in my studio everyday. I walk -- I'm traveling. I come back. Some guy's got that on a computer -- there's this like, oh my goodness. So I try to create this energy of invention every day in my studio. This kind of effervescent -- fully charged sense of soup that delivers ideas.

Single-surface products. Furniture's a good one. How you grow legs out of a surface. I would love to build this one day and perhaps I'd like to build it also out of flour, sugar, polymer, wood chips -- I don't know, human hair. I don't know. I'd love a go at that. I don't know. If I just got some time. That's the weird side coming out again. A lot of companies don't understand that.

Three weeks ago I was with Sony in Tokyo. They said, "Give us the dream. What is our dream? How do we beat Apple?" I said, "You don't copy Apple, that's for sure. You get into biopolymers." They looked straight through me. What a waste. Anyway.

(Laughter)

No, it's true. Fuck them. You know, I mean --

(Laughter)

I'm delivering; they're not taking. I've had this image 20 years. I've had this image of a water droplet for 20 years, sitting on a hot bed. That is an image of a car for me. That's the car of the future. It's a water droplet. I've been banging on about this like I can't believe. Cars are all wrong.

I'm going to show you something a bit weird now. They laughed everywhere over the world I showed this. The only place that didn't laugh was Moscow. Cars are made from 30,000 components. How ridiculous is that? Couldn't you make that from 300? It's got a vacuum-formed, carbon-nylon pan. Everything's holistically integrated. It opens and closes like a bread bin. There is no engine. There's a solar panel on the back and there are batteries in the wheels; they're fitted like Formula 1. You take them off your wall, you plug them in. Off you go. A three-wheeled car: slow, feminine, transparent, so you can see the people in there. You drive different. You see that thing. You do. You do. And not anesthetized, separated from life. There's a hole at the front and there's a reason for that. It's a city car. You drive along. You get out. You drive on to a proboscis. You get out. It lifts you up. It presents the solar panel to the sun, and at night, it's a street lamp.

(Applause)

That's what happens if you get inspired by the street lamp first, and do the car second. I can see these bubbles with these hydrogen packages, floating around on the ground, driven by AI. When I showed this in South Africa, everybody afterwards was going, "Hey, car on a stick. Like this." Can you imagine? A car on a stick.

(Laughter)

If you put it next to contemporary architecture, it feels totally natural to me. And that's what I do with my furniture. I'm not putting Charles Eames' furniture in buildings anymore. I'm trying to build furniture which fits architecture. I'm trying to build transportation systems. I work on aircraft for Airbus, I do all this sort of stuff trying to force these natural, inspired-by-nature dreams home.

I'm going to finish on two things. This is the stereolithography of a staircase. It's a little bit of a dedication to James, James Watson. I built this thing for my studio. It cost me 250,000 dollars to build this. Most people go and buy the Aston Martin. I built this. This is the data that goes with that. Incredibly complex. Took about two years, because I'm looking for fat-free design. Lean, efficient things. Healthy products. This is built by composites. It's a single element which rotates around to create a holistic element, and this is a carbon-fiber handrail which is only supported in two places. Modern materials allow us to do modern things.

This is a shot in the studio. This is how it looks pretty much every day. You wouldn't want to have a fear of heights coming down it. There is virtually no handrail. It doesn't pass any standards.

(Laughter)

Who cares?

(Laughter)

And it has an internal handrail which gives it its strength. It's this holistic integration. That's my studio. It's subterranean. It's in Notting Hill, next to all the crap -- the prostitutes and all that stuff. It's next to David Hockney's original studio. It has a lighting system that changes throughout the day. My guys go out for lunch. The door's open. They come back in, because it's normally raining and they prefer to stay in.

This is my studio. Elephant skull from Oxford University, 1988. I bought that last year. They're very difficult to find. If anybody's got a whale skeleton they want to sell me, I'll put it in the studio.

So I'm just going to interject a little bit with some of the things that you'll see in the video. It's a homemade video, made it myself at three o'clock in the morning just to show you how my real world is. You never see that. You never see architects or designers showing you their real world.

This is called a "Plasnet." It's a new bio-polycarbonate chair I'm doing in Italy.

World's first bamboo bike with folding handlebars. We should all be riding one of these. As China buys all these crappy cars, we should be riding things like this. Counterbalance.

Like I say, it's a cross between Natural History Museum and a NASA laboratory. It's full of prototypes and objects. It's self-inspirational, again. I mean, the rare times when I'm there, I do enjoy it. And I get lots and lots of kids coming. I'm a contaminator for all those children of investment bankers -- wankers. Sorry.

(Laughter)

That's a solar seed. It's a concept for new architecture. That thing on the top is the world's first solar-powered garden lamp -- the first produced. Giles Revell should be talking here today -- amazing photography of things you can't see.

The first sculptural model I made for that thing in Tokyo.

Lots of stuff. There's a little leaf chair -- that golden looking thing is called "Leaf." It's made from Kevlar.

On the wall is my book called "Supernatural," which allows me to remember what I've done, because I forget.

There's an aerated brick I did in Limoges last year, in Concepts for New Ceramics in Architecture.

Gernot Oberfell, working at three o'clock in the morning -- and I don't pay overtime. Overtime is the passion of design, so join the club or don't.

(Laughter)

No, it's true. People like Tom and Greg -- we're traveling like you can't -- we fit it all in. I don't know how we do it.

Next week I'm at Electrolux in Sweden, then I'm in Beijing on Friday. You work that one out. And when I see Ed's photographs, I think, why the hell am I going to China? It's true. It's true. Because there's a soul in this whole thing. We need to have a new instinct for the 21st century. We need to combine all this stuff. If all the people who were talking over this period worked on a car together, it would be a joy, absolute joy.

So there's a new X-light system I'm doing in Japan.

There's Tuareg shoes from North Africa. There's a Kifwebe mask.

These are my sculptures.

A copper jelly mold.

(Laughter)

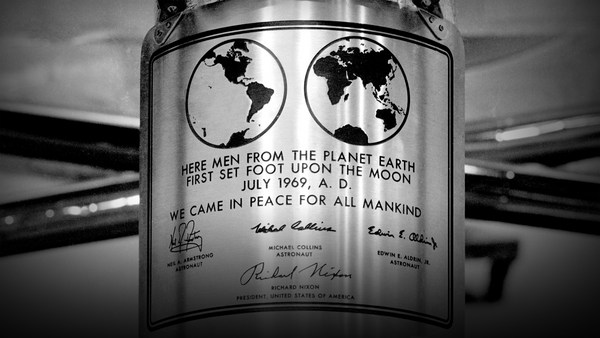

It sounds like some quiz show or something, doesn't it? So, it's going to end. Thank you, James, for your great inspiration.

Thank you very much.

(Applause)