I want you to imagine that you're a student in my lab. What I want you to do is to create a biologically inspired design. And so here's the challenge: I want you to help me create a fully 3D, dynamic, parameterized contact model. The translation of that is, could you help me build a foot? And it is a true challenge, and I do want you to help me. Of course, in the challenge there is a prize. It's not quite the TED Prize, but it is an exclusive t-shirt from our lab. So please send me your ideas about how to design a foot.

Now if we want to design a foot, what do we have to do? We have to first know what a foot is. If we go to the dictionary, it says, "It's the lower extremity of a leg that is in direct contact with the ground in standing or walking" That's the traditional definition. But if you wanted to really do research, what do you have to do? You have to go to the literature and look up what's known about feet. So you go to the literature. (Laughter)

Maybe you're familiar with this literature. The problem is, there are many, many feet. How do you do this? You need to survey all feet and extract the principles of how they work. And I want you to help me do that in this next clip. As you see this clip, look for principles, and also think about experiments that you might design in order to understand how a foot works.

See any common themes? Principles? What would you do? What experiments would you run? Wow. (Applause) Our research on the biomechanics of animal locomotion has allowed us to make a blueprint for a foot. It's a design inspired by nature, but it's not a copy of any specific foot you just looked at, but it's a synthesis of the secrets of many, many feet.

Now it turns out that animals can go anywhere. They can locomote on substrates that vary as you saw -- in the probability of contact, the movement of that surface and the type of footholds that are present. If you want to study how a foot works, we're going to have to simulate those surfaces, or simulate that debris. When we did that, here's a new experiment that we did: we put an animal and had it run -- this grass spider -- on a surface with 99 percent of the contact area removed. But it didn't even slow down the animal. It's still running at the human equivalent of 300 miles per hour.

Now how could it do that? Well, look more carefully. When we slow it down 50 times we see how the leg is hitting that simulated debris. The leg is acting as a foot. And in fact, the animal contacts other parts of its leg more frequently than the traditionally defined foot. The foot is distributed along the whole leg. You can do another experiment where you can take a cockroach with a foot, and you can remove its foot. I'm passing some cockroaches around. Take a look at their feet. Without a foot, here's what it does. It doesn't even slow down. It can run the same speed without even that segment. No problem for the cockroach -- they can grow them back, if you care. How do they do it? Look carefully: this is slowed down 100 times, and watch what it's doing with the rest of its leg. It's acting, again, as a distributed foot -- very effective.

Now, the question we had is, how general is a distributed foot? And the next behavior I'll show you of this animal just stunned us the first time that we saw it. Journalists, this is off the record; it's embargoed. Take a look at what that is! That's a bipedal octopus that's disguised as a rolling coconut. It was discovered by Christina Huffard and filmed by Sea Studios, right here from Monterey.

We've also described another species of bipedal octopus. This one disguises itself as floating algae. It walks on two legs and it holds the other arms up in the air so that it can't be seen. (Applause) And look what it does with its foot to get over challenging terrain. It uses that beautiful distributed foot to make it as if those obstacles are not even there -- truly extraordinary.

In 1951, Escher made this drawing. He thought he created an animal fantasy. But we know that art imitates life, and it turns out nature, three million years ago, evolved the next animal. It's a shrimp-like animal called the stomatopod, and here's how it moves on the beaches of Panama: it actually rolls, and it can even roll uphill. It's the ultimate distributed foot: its whole body in this case is acting like its foot.

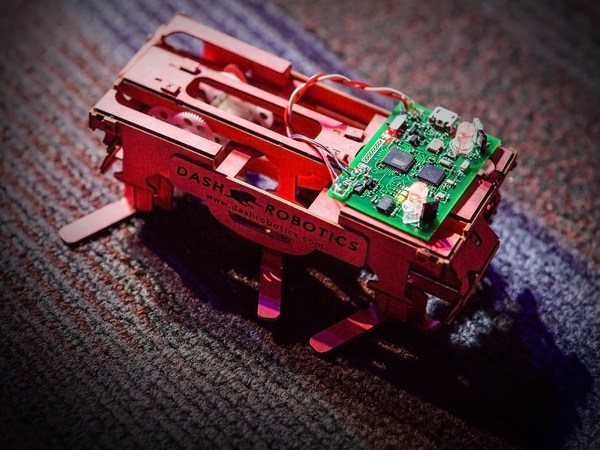

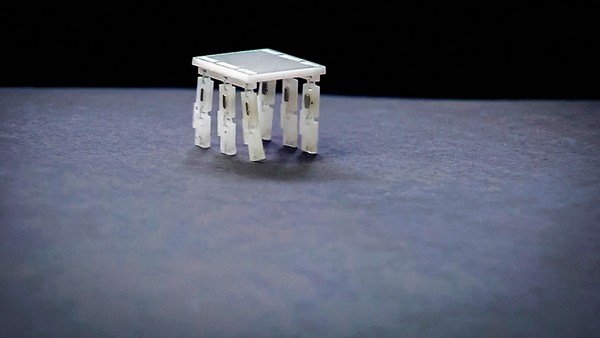

So, if we want to then, to our blueprint, add the first important feature, we want to add distributed foot contact. Not just with the traditional foot, but also the leg, and even of the body. Can this help us inspire the design of novel robots? We biologically inspired this robot, named RHex, built by these extraordinary engineers over the last few years. RHex's foot started off to be quite simple, then it got tuned over time, and ultimately resulted in this half circle. Why is that? The video will show you. Watch where the robot, now, contacts its leg in order to deal with this very difficult terrain. What you'll see, in fact, is that it's using that half circle leg as a distributed foot. Watch it go over this. You can see it here well on this debris. Extraordinary. No sensing, all the control is built right into the tuned legs. Really simple, but beautiful.

Now, you might have noticed something else about the animals when they were running over the rough terrain. And my assistant's going to help me here. When you touched the cockroach leg -- can you get the microphone for him? When you touched the cockroach leg, what did it feel like? Did you notice something?

Boy: Spiny.

Robert Full: It's spiny, right? It's really spiny, isn't it? It sort of hurts. Maybe we could give it to our curator and see if he'd be brave enough to touch the cockroach. (Laughter)

Chris Anderson: Did you touch it?

RF: So if you look carefully at this, what you see is that they have spines and until a few weeks ago, no one knew what they did. They assumed that they were for protection and for sensory structures. We found that they're for something else -- here's a segment of that spine. They're tuned such that they easily collapse in one direction to pull the leg out from debris, but they're stiff in the other direction so they capture disparities in the surface.

Now crabs don't miss footholds, because they normally move on sand -- until they come to our lab. And where they have a problem with this kind of mesh, because they don't have spines. The crabs are missing spines, so they have a problem in this kind of rough terrain. But of course, we can deal with that because we can produce artificial spines. We can make spines that catch on simulated debris and collapse on removal to easily pull them out. We did that by putting these artificial spines on crabs, as you see here, and then we tested them. Do we really understand that principle of tuning? The answer is, yes! This is slowed down 20-fold, and the crab just zooms across that simulated debris. (Laughter) (Applause) A little better than nature.

So to our blueprint, we need to add tuned spines. Now will this help us think about the design of more effective climbing robots? Well, here's RHex: RHex has trouble on rails -- on smooth rails, as you see here. So why not add a spine? My colleagues did this at U. Penn. Dan Koditschek put some steel nails -- very simple version -- on the robot, and here's RHex, now, going over those steel -- those rails. No problem! How does it do it? Let's slow it down and you can see the spines in action. Watch the leg come around, and you'll see it grab on right there. It couldn't do that before; it would just slip and get stuck and tip over. And watch again, right there -- successful.

Now just because we have a distributed foot and spines doesn't mean you can climb vertical surfaces. This is really, really difficult. But look at this animal do it! One of the ones I'm passing around is climbing up this vertical surface that's a smooth metal plate. It's extraordinary how fast it can do it -- but if you slow it down, you see something that's quite extraordinary. It's a secret. The animal effectively climbs by slipping and look -- and doing, actually, terribly, with respect to grabbing on the surface. It looks, in fact, like it's swimming up the surface. We can actually model that behavior better as a fluid, if you look at it. The distributed foot, actually, is working more like a paddle.

The same is true when we looked at this lizard running on fluidized sand. Watch its feet. It's actually functioning as a paddle even though it's interacting with a surface that we normally think of as a solid. This is not different from what my former undergraduate discovered when she figured out how lizards can run on water itself. Can you use this to make a better robot? Martin Buehler did -- who's now at Boston Dynamics -- he took this idea and made RHex to be Aqua RHex. So here's RHex with paddles, now converted into an incredibly maneuverable swimming robot.

For rough surfaces, though, animals add claws. And you probably feel them if you grabbed it. Did you touch it?

CA: I did.

RF: And they do really well at grabbing onto surfaces with these claws. Mark Cutkosky at Stanford University, one of my collaborators, is an extraordinary engineer who developed this technique called Shape Deposition Manufacturing, where he can imbed claws right into an artificial foot. And here's the simple version of a foot for a new robot that I'll show you in a bit. So to our blueprint, let's attach claws. Now if we look at animals, though, to be really maneuverable in all surfaces, the animals use hybrid mechanisms that include claws, and spines, and hairs, and pads, and glue, and capillary adhesion and a whole bunch of other things. These are all from different insects. There's an ant crawling up a vertical surface. Let's look at that ant.

This is the foot of an ant. You see the hairs and the claws and this thing here. This is when its foot's in the air. Watch what happens when the foot goes onto your sandwich. You see what happens? That pad comes out. And that's where the glue is. Here from underneath is an ant foot, and when the claws don't dig in, that pad automatically comes out without the ant doing anything. It just extrudes. And this was a hard shot to get -- I think this is the shot of the ant foot on the superstrings. So it's pretty tough to do. This is what it looks like close up -- here's the ant foot, and there's the glue.

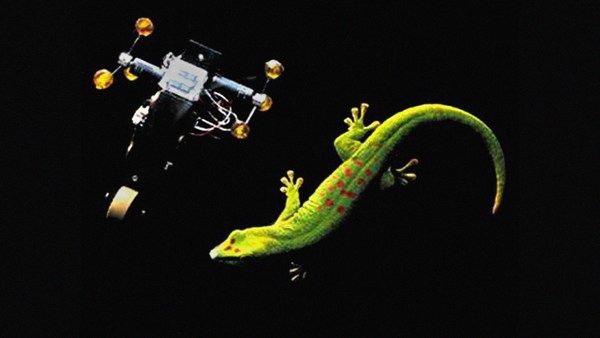

And we discovered this glue may be an interesting two-phase mixture. It certainly helps it to hold on. So to our blueprint, we stick on some sticky pads. Now you might think for smooth surfaces we get inspiration here. Now we have something better here. The gecko's a really great example of nanotechnology in nature. These are its feet. They're -- almost look alien. And the secret, which they stick on with, involves their hairy toes. They can run up a surface at a meter per second, take 30 steps in that one second -- you can hardly see them. If we slow it down, they attach their feet at eight milliseconds, and detach them in 16 milliseconds. And when you watch how they detach it, it is bizarre. They peel away from the surface like you'd peel away a piece of tape. Very strange. How do they stick?

If you look at their feet, they have leaf-like structures called linalae with millions of hairs. And each hair has the worst case of split ends possible. It has a hundred to a thousand split ends, and that's the secret, because it allows intimate contact. The gecko has a billion of these 200-nanometer-sized split ends. And they don't stick by glue, or they don't work like Velcro, or they don't work with suction. We discovered they work by intermolecular forces alone. So to our blueprint, we split some hairs. This has inspired the design of the first self-cleaning dry adhesive -- the patent issued, we're happy to say. And here's the simplest version in nature, and here's my collaborator Ron Fearing's attempt at an artificial version of this dry adhesive made from polyurethane. And here's the first attempt to have it work on some load.

There's enormous interest in this in a variety of different fields. You could think of a thousand possible uses, I'm sure. Lots of people have, and we're excited about realizing this as a product. We have imagined products; for example, this one: we imagined a bio-inspired Band-Aid, where we took the glue off the Band-Aid. We took some hairs from a molting gecko; put three rolls of them on here, and then made this Band-Aid.

This is an undergraduate volunteer -- we have 30,000 undergraduates so we can choose among them -- that's actually just a red pen mark. But it makes an incredible Band-Aid. It's aerated, it can be peeled off easily, it doesn't cause any irritation, it works underwater. I think this is an extraordinary example of how curiosity-based research -- we just wondered how they climbed up something -- can lead to things that you could never imagine. It's just an example of why we need to support curiosity-based research. Here you are, pulling off the Band-Aid.

So we've redefined, now, what a foot is. The question is, can we use these secrets, then, to inspire the design of a better foot, better than one that we see in nature? Here's the new project: we're trying to create the first climbing search-and-rescue robot -- no suction or magnets -- that can only move on limited kinds of surfaces. I call the new robot RiSE, for "Robot in Scansorial Environment" -- that's a climbing environment -- and we have an extraordinary team of biologists and engineers creating this robot. And here is RiSE. It's six-legged and has a tail. Here it is on a fence and a tree. And here are RiSE's first steps on an incline. You have the audio? You can hear it go up. And here it is coming up at you, in its first steps up a wall. Now it's only using its simplest feet here, so this is very new. But we think we got the dynamics right of the robot.

Mark Cutkosky, though, is taking it a step further. He's the one able to build this shape-deposition manufactured feet and toes. The next step is to make compliant toes, and try to add spines and claws and set it for dry adhesives. So the idea is to first get the toes and a foot right, attempt to make that climb, and ultimately put it on the robot. And that's exactly what he's done. He's built, in fact, a climbing foot-bot inspired by nature.

And here's Cutkosky's and his amazing students' design. So these are tuned toes -- there are six of them, and they use the principles that I just talked about collectively for the blueprint. So this is not using any suction, any glue, and it will ultimately, when it's attached to the robot -- it's as biologically inspired as the animal -- hopefully be able to climb any kind of a surface. Here you see it, next, going up the side of a building at Stanford. It's sped up -- again, it's a foot climbing. It's not the whole robot yet, we're working on it -- now you can see how it's attaching. These tuned structures allow the spines, friction pads and ultimately the adhesive hairs to grab onto very challenging, difficult surfaces. And so they were able to get this thing -- this is now sped up 20 times -- can you imagine it trying to go up and rescue somebody at that upper floor? OK? You can visualize this now; it's not impossible. It's a very challenging task. But more to come later.

To finish: we've gotten design secrets from nature by looking at how feet are built. We've learned we should distribute control to smart parts. Don't put it all in the brain, but put some of the control in tuned feet, legs and even body. That nature uses hybrid solutions, not a single solution, to these problems, and they're integrated and beautifully robust. And third, we believe strongly that we do not want to mimic nature but instead be inspired by biology, and use these novel principles with the best engineering solutions that are out there to make -- potentially -- something better than nature.

So there's a clear message: whether you care about a fundamental, basic research of really interesting, bizarre, wonderful animals, or you want to build a search-and-rescue robot that can help you in an earthquake, or to save someone in a fire, or you care about medicine, we must preserve nature's designs. Otherwise these secrets will be lost forever. Thank you.