Let me share with you today an original discovery. But I want to tell it to you the way it really happened -- not the way I present it in a scientific meeting, or the way you'd read it in a scientific paper. It's a story about beyond biomimetics, to something I'm calling biomutualism. I define that as an association between biology and another discipline, where each discipline reciprocally advances the other, but where the collective discoveries that emerge are beyond any single field. Now, in terms of biomimetics, as human technologies take on more of the characteristics of nature, nature becomes a much more useful teacher. Engineering can be inspired by biology by using its principles and analogies when they're advantageous, but then integrating that with the best human engineering, ultimately to make something actually better than nature.

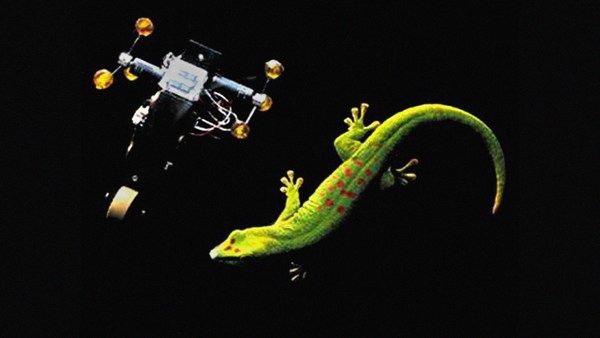

Now, being a biologist, I was very curious about this. These are gecko toes. And we wondered how they use these bizarre toes to climb up a wall so quickly. We discovered it. And what we found was that they have leaf-like structures on their toes, with millions of tiny hairs that look like a rug, and each of those hairs has the worst case of split-ends possible: about 100 to 1000 split ends that are nano-size. And the individual has 2 billion of these nano-size split ends. They don't stick by Velcro or suction or glue. They actually stick by intermolecular forces alone, van der Waals forces. And I'm really pleased to report to you today that the first synthetic self-cleaning, dry adhesive has been made. From the simplest version in nature, one branch, my engineering collaborator, Ron Fearing, at Berkeley, had made the first synthetic version. And so has my other incredible collaborator, Mark Cutkosky, at Stanford -- he made much larger hairs than the gecko, but used the same general principles.

And here is its first test. (Laughter) That's Kellar Autumn, my former Ph.D. student, professor now at Lewis and Clark, literally giving his first-born child up for this test. (Laughter)

More recently, this happened.

Man: This the first time someone has actually climbed with it.

Narrator: Lynn Verinsky, a professional climber, who appeared to be brimming with confidence.

Lynn Verinsky: Honestly, it's going to be perfectly safe. It will be perfectly safe.

Man: How do you know?

Lynn Verinsky: Because of liability insurance. (Laughter)

Narrator: With a mattress below and attached to a safety rope, Lynn began her 60-foot ascent. Lynn made it to the top in a perfect pairing of Hollywood and science.

Man: So you're the first human being to officially emulate a gecko.

Lynn Verinsky: Ha! Wow. And what a privilege that has been.

Robert Full: That's what she did on rough surfaces. But she actually used these on smooth surfaces -- two of them -- to climb up, and pull herself up. And you can try this in the lobby, and look at the gecko-inspired material. Now the problem with the robots doing this is that they can't get unstuck, with the material. This is the gecko's solution. They actually peel their toes away from the surface, at high rates, as they run up the wall.

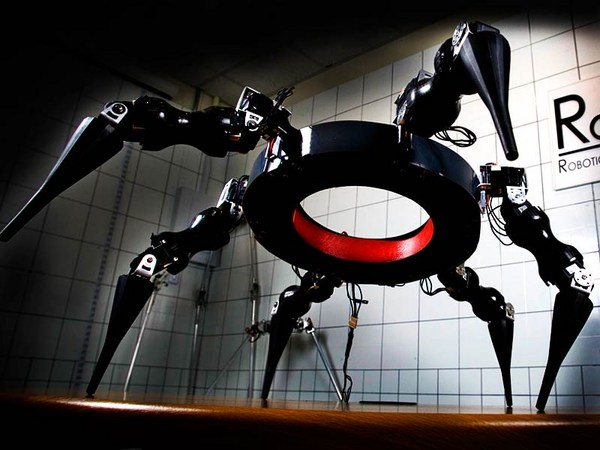

Well I'm really excited today to show you the newest version of a robot, Stickybot, using a new hierarchical dry adhesive. Here is the actual robot. And here is what it does. And if you look, you can see that it uses the toe peeling, just like the gecko does. If we can show some of the video, you can see it climbing up the wall. (Applause) There it is. And now it can go on other surfaces because of the new adhesive that the Stanford group was able to do in designing this incredible robot. (Applause)

Oh. One thing I want to point out is, look at Stickybot. You see something on it. It's not just to look like a gecko. It has a tail. And just when you think you've figured out nature, this kind of thing happens. The engineers told us, for the climbing robots, that, if they don't have a tail, they fall off the wall. So what they did was they asked us an important question. They said, "Well, it kind of looks like a tail." Even though we put a passive bar there. "Do animals use their tails when they climb up walls?" What they were doing was returning the favor, by giving us a hypothesis to test, in biology, that we wouldn't have thought of.

So of course, in reality, we were then panicked, being the biologists, and we should know this already. We said, "Well, what do tails do?" Well we know that tails store fat, for example. We know that you can grab onto things with them. And perhaps it is most well known that they provide static balance. (Laughter) It can also act as a counterbalance. So watch this kangaroo. See that tail? That's incredible! Marc Raibert built a Uniroo hopping robot. And it was unstable without its tail. Now mostly tails limit maneuverability, like this human inside this dinosaur suit. (Laughter) My colleagues actually went on to test this limitation, by increasing the moment of inertia of a student, so they had a tail, and running them through and obstacle course, and found a decrement in performance, like you'd predict. (Laughter) But of course, this is a passive tail. And you can also have active tails.

And when I went back to research this, I realized that one of the great TED moments in the past, from Nathan, we've talked about an active tail.

Video: Myhrvold thinks tail-cracking dinosaurs were interested in love, not war.

Robert Full: He talked about the tail being a whip for communication. It can also be used in defense. Pretty powerful. So we then went back and looked at the animal. And we ran it up a surface. But this time what we did is we put a slippery patch that you see in yellow there. And watch on the right what the animal is doing with its tail when it slips. This is slowed down 10 times. So here is normal speed. And watch it now slip, and see what it does with its tail. It has an active tail that functions as a fifth leg, and it contributes to stability. If you make it slip a huge amount, this is what we discovered. This is incredible. The engineers had a really good idea.

And then of course we wondered, okay, they have an active tail, but let's picture them. They're climbing up a wall, or a tree. And they get to the top and let's say there's some leaves there. And what would happen if they climbed on the underside of that leaf, and there was some wind, or we shook it? And we did that experiment, that you see here. (Applause) And this is what we discovered. Now that's real time. You can't see anything. But there it is slowed down.

What we discovered was the world's fastest air-righting response. For those of you who remember your physics, that's a zero-angular-momentum righting response. But it's like a cat. You know, cats falling. Cats do this. They twist their bodies. But geckos do it better. And they do it with their tail. So they do it with this active tail as they swing around. And then they always land in the sort of superman skydiving posture. Okay, now we wondered, if we were right, we should be able to test this in a physical model, in a robot.

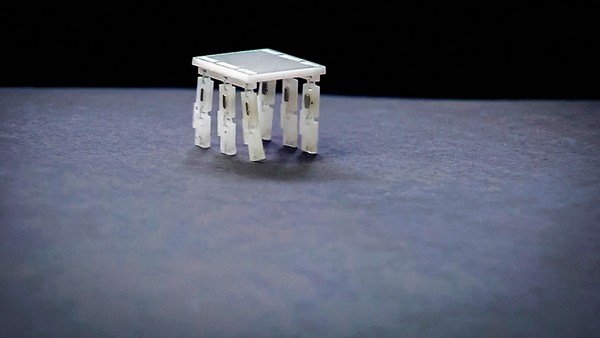

So for TED we actually built a robot, over there, a prototype, with the tail. And we're going to attempt the first air-righting response in a tail, with a robot. If we could have the lights on it. Okay, there it goes. And show the video. There it is. And it works just like it does in the animal. So all you need is a swing of the tail to right yourself. (Applause)

Now, of course, we were normally frightened because the animal has no gliding adaptations, so we thought, "Oh that's okay. We'll put it in a vertical wind tunnel. We'll blow the air up, we'll give it a landing target, a tree trunk, just outside the plexi-glass enclosure, and see what it does. (Laughter) So we did. And here is what it does. So the wind is coming from the bottom. This is slowed down 10 times. It does an equilibrium glide. Highly controlled. This is sort of incredible. But actually it's quite beautiful, when you take a picture of it. And it's better than that, it -- just in the slide -- maneuvers in mid-air. And the way it does it, is it takes its tail and it swings it one way to yaw left, and it swings its other way to yaw right. So we can maneuver this way. And then -- we had to film this several times to believe this -- it also does this. Watch this. It oscillates its tail up and down like a dolphin. It can actually swim through the air. But watch its front legs. Can you see what they are doing? What does that mean for the origin of flapping flight? Maybe it's evolved from coming down from trees, and trying to control a glide. Stay tuned for that. (Laughter)

So then we wondered, "Can they actually maneuver with this?" So there is the landing target. Could they steer towards it with these capabilities? Here it is in the wind tunnel. And it certainly looks like it. You can see it even better from down on top. Watch the animal. Definitely moving towards the landing target. Watch the whip of its tail as it does it. Look at that. It's unbelievable.

So now we were really confused, because there are no reports of it gliding. So we went, "Oh my god, we have to go to the field, and see if it actually does this." Completely opposite of the way you'd see it on a nature film, of course. We wondered, "Do they actually glide in nature?" Well we went to the forests of Singapore and Southeast Asia. And the next video you see is the first time we've showed this.

This is the actual video -- not staged, a real research video -- of animal gliding down. There is a red trajectory line. Look at the end to see the animal. But then as it gets closer to the tree, look at the close-up. And see if you can see it land. So there it comes down. There is a gecko at the end of that trajectory line. You see it there? There? Watch it come down. Now watch up there and you can see the landing. Did you see it hit? It actually uses its tail too, just like we saw in the lab.

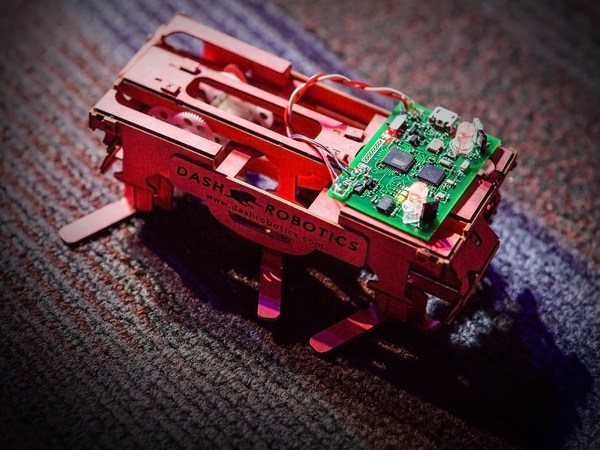

So now we can continue this mutualism by suggesting that they can make an active tail. And here is the first active tail, in the robot, made by Boston Dynamics. So to conclude, I think we need to build biomutualisms, like I showed, that will increase the pace of basic discovery in their application. To do this though, we need to redesign education in a major way, to balance depth with interdisciplinary communication, and explicitly train people how to contribute to, and benefit from other disciplines. And of course you need the organisms and the environment to do it. That is, whether you care about security, search and rescue or health, we must preserve nature's designs, otherwise these secrets will be lost forever. And from what I heard from our new president, I'm very optimistic. Thank you. (Applause)