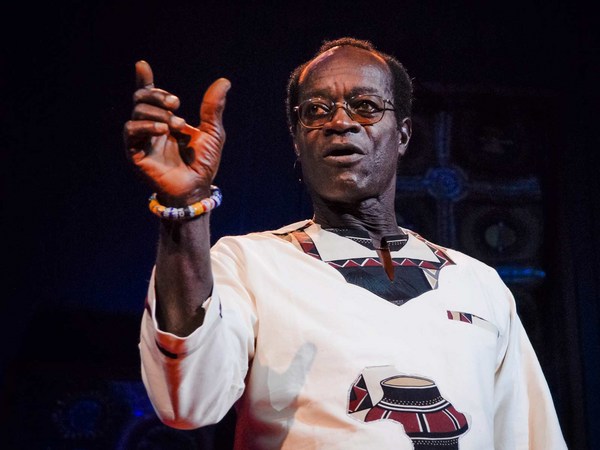

Take a look at this picture. It poses a very fascinating puzzle for us. These African students are doing their homework under streetlights at the airport in the capital city because they don't have any electricity at home. Now, I haven't met these particular students, but I've met students like them.

Let's just pick one -- for example, the one in the green shirt. Let's give him a name, too: Nelson. I'll bet Nelson has a cellphone. So here is the puzzle. Why is it that Nelson has access to a cutting-edge technology, like the cellphone, but doesn't have access to a 100-year-old technology for generating electric light in the home?

Now, in a word, the answer is "rules." Bad rules can prevent the kind of win-win solution that's available when people can bring new technologies in and make them available to someone like Nelson. What kinds of rules? The electric company in this nation operates under a rule, which says that it has to sell electricity at a very low, subsidized price -- in fact, a price that is so low it loses money on every unit that it sells. So it has neither the resources, nor the incentives, to hook up many other users.

The president wanted to change this rule. He's seen that it's possible to have a different set of rules, rules where businesses earn a small profit, so they have an incentive to sign up more customers. That's the kind of rules that the cellphone company that Nelson purchases his telephony from operates under. The president has seen how those rules worked well. So he tried to change the rules for pricing on electricity, but ran into a firestorm of protest from businesses and consumers who wanted to preserve the existing subsidized rates. So he was stuck with rules that prevented him from letting the win-win solution help his country. And Nelson is stuck studying under the streetlights.

The real challenge then, is to try to figure out how we can change rules. Are there some rules we can develop for changing rules? I want to argue that there is a general abstract insight that we can make practical, which is that, if we can give more choices to people, and more choices to leaders -- who, in many countries, are also people. (Laughter) But, it's useful to present the opposition between these two. Because the kind of choice you might want to give to a leader, a choice like giving the president the choice to raise prices on electricity, takes away a choice that people in the economy want. They want the choice to be able to continue consuming subsidized electric power. So if you give just to one side or the other, you'll have tension or friction. But if we can find ways to give more choices to both, that will give us a set of rules for changing rules that get us out of traps.

Now, Nelson also has access to the Internet. And he says that if you want to see the damaging effects of rules, the ways that rules can keep people in the dark, look at the pictures from NASA of the earth at night. In particular check out Asia. If you zoom in here, you can see North Korea, in outline here, which is like a black hole compared to its neighbors. Now, you won't be surprised to learn that the rules in North Korea keep people there in the dark.

But it is important to recognize that North Korea and South Korea started out with identical sets of rules in both the sense of laws and regulations, but also in the deeper senses of understandings, norms, culture, values and beliefs. When they separated, they made choices that led to very divergent paths for their sets of rules. So we can change -- we as humans can change the rules that we use to interact with each other, for better, or for worse.

Now let's look at another region, the Caribbean. Zoom in on Haiti, in outline here. Haiti is also dark, compared to its neighbor here, the Dominican Republic, which has about the same number of residents. Both of these countries are dark compared to Puerto Rico, which has half as many residents as either Haiti or the Dominican Republic. What Haiti warns us is that rules can be bad because governments are weak. It's not just that the rules are bad because the government is too strong and oppressive, as in North Korea. So that if we want to create environments with good rules, we can't just tear down. We've got to find ways to build up, as well.

Now, China dramatically demonstrates both the potential and the challenges of working with rules. Back in the beginning of the data presented in this chart, China was the world's high-technology leader. Chinese had pioneered technologies like steel, printing, gunpowder. But the Chinese never adopted, at least in that period, effective rules for encouraging the spread of those ideas -- a profit motive that could have encouraged the spread. And they soon adopted rules which slowed down innovation and cut China off from the rest of the world. So as other countries in the world innovated, in the sense both of developing newer technologies, but also developing newer rules, the Chinese were cut off from those advances. Income there stayed stagnant, as it zoomed ahead in the rest of the world.

This next chart looks at more recent data. It plots income, average income in China as a percentage of average income in the United States. In the '50s and '60s you can see that it was hovering at about three percent. But then in the late '70s something changed. Growth took off in China. The Chinese started catching up very quickly with the United States.

If you go back to the map at night, you can get a clue to the process that lead to the dramatic change in rules in China. The brightest spot in China, which you can see on the edge of the outline here, is Hong Kong. Hong Kong was a small bit of China that, for most of the 20th century, operated under a very different set of rules than the rest of mainland China -- rules that were copied from working market economies of the time, and administered by the British.

In the 1950s, Hong Kong was a place where millions of people could go, from the mainland, to start in jobs like sewing shirts, making toys. But, to get on a process of increasing income, increasing skills led to very rapid growth there. Hong Kong was also the model which leaders like Deng Xiaoping could copy, when they decided to move all of the mainland towards the market model.

But Deng Xiaoping instinctively understood the importance of offering choices to his people. So instead of forcing everyone in China to shift immediately to the market model, they proceeded by creating some special zones that could do, in a sense, what Britain did: make the opportunity to go work with the market rules available to the people who wanted to opt in there. So they created four special economic zones around Hong Kong: zones where Chinese could come and work, and cities grew up very rapidly there; also zones where foreign firms could come in and make things.

One of the zones next to Hong Kong has a city called Shenzhen. In that city there is a Taiwanese firm that made the iPhone that many of you have, and they made it with labor from Chinese who moved there to Shenzhen. So after the four special zones, there were 14 coastal cites that were open in the same sense, and eventually demonstrated successes in these places that people could opt in to, that they flocked to because of the advantages they offered. Demonstrated successes there led to a consensus for a move toward the market model for the entire economy.

Now the Chinese example shows us several points. One is: preserve choices for people. Two: operate on the right scale. If you try to change the rules in a village, you could do that, but a village would be too small to get the kinds of benefits you can get if you have millions of people all working under good rules. On the other hand, the nation is too big. If you try to change the rules in the nation, you can't give some people a chance to hold back, see how things turn out, and let others zoom ahead and try the new rules. But cities give you this opportunity to create new places, with new rules that people can opt in to. And they're large enough to get all of the benefits that we can have when millions of us work together under good rules.

So the proposal is that we conceive of something called a charter city. We start with a charter that specifies all the rules required to attract the people who we'll need to build the city. We'll need to attract the investors who will build out the infrastructure -- the power system, the roads, the port, the airport, the buildings. You'll need to attract firms, who will come hire the people who move there first. And you'll need to attract families, the residents who will come and live there permanently, raise their children, get an education for their children, and get their first job.

With that charter, people will move there. The city can be built. And we can scale this model. We can go do it over and over again. To make it work, we need good rules. We've already discussed that. Those are captured in the charter. We also need the choices for people. That's really built into the model if we allow for the possibility of building cities on uninhabited land. You start from uninhabited territory. People can come live under the new charter, but no one is forced to live under it. The final thing we need are choices for leaders.

And, to achieve the kind of choices we want for leaders we need to allow for the potential for partnerships between nations: cases where nations work together, in effect, de facto, the way China and Britain worked together to build, first a little enclave of the market model, and then scale it throughout China. In a sense, Britain, inadvertently, through its actions in Hong Kong, did more to reduce world poverty than all the aid programs that we've undertaken in the last century. So if we allow for these kind of partnerships to replicate this again, we can get those kinds of benefits scaled throughout the world.

In some cases this will involve a delegation of responsibility, a delegation of control from one country to another to take over certain kinds of administrative responsibilities. Now, when I say that, some of you are starting to think, "Well, is this just bringing back colonialism?" It's not. But it's important to recognize that the kind of emotions that come up when we start to think about these things, can get in the way, can make us pull back, can shut down our ability, and our interest in trying to explore new ideas.

Why is this not like colonialism? The thing that was bad about colonialism, and the thing which is residually bad in some of our aid programs, is that it involved elements of coercion and condescension. This model is all about choices, both for leaders and for the people who will live in these new places. And, choice is the antidote to coercion and condescension.

So let's talk about how this could play out in practice. Let's take a particular leader, Raul Castro, who is the leader of Cuba. It must have occurred to Castro that he has the chance to do for Cuba what Deng Xiaoping did for China, but he doesn't have a Hong Kong there on the island in Cuba. He does, though, have a little bit of light down in the south that has a very special status. There is a zone there, around Guantanamo Bay, where a treaty gives the United States administrative responsibility for a piece of land that's about twice the size of Manhattan.

Castro goes to the prime minister of Canada and says, "Look, the Yankees have a terrible PR problem. They want to get out. Why don't you, Canada, take over? Build -- run a special administrative zone. Allow a new city to be built up there. Allow many people to come in. Let us have a Hong Kong nearby. Some of my citizens will move into that city as well. Others will hold back. But this will be the gateway that will connect the modern economy and the modern world to my country."

Now, where else might this model be tried? Well, Africa. I've talked with leaders in Africa. Many of them totally get the notion of a special zone that people can opt into as a rule. It's a rule for changing rules. It's a way to create new rules, and let people opt-in without coercion, and the opposition that coercion can force. They also totally get the idea that in some instances they can make more credible promises to long-term investors -- the kind of investors who will come build the port, build the roads, in a new city --

they can make more credible promises if they do it along with a partner nation. Perhaps even in some arrangement that's a little bit like an escrow account, where you put land in the escrow account and the partner nation takes responsibility for it. There is also lots of land in Africa where new cities could be built. This is a picture I took when I was flying along the coast. There are immense stretches of land like this -- land where hundreds of millions of people could live. Now, if we generalize this and think about not just one or two charter cites, but dozens -- cities that will help create places for the many hundreds of millions, perhaps billions of people who will move to cities in the coming century --

is there enough land for them? Well, throughout the world, if we look at the lights at night, the one thing that's misleading is that, visually, it looks like most of the world is already built out. So let me show you why that's wrong. Take this representation of all of the land. Turn it into a square that stands for all the arable land on Earth. And let these dots represent the land that's already taken up by the cities that three billion people now live in. If you move the dots down to the bottom of the rectangle you can see that the cities for the existing three billion urban residents take up only three percent of the arable land on earth.

So if we wanted to build cities for another billion people, they would be dots like this. We'd go from three percent of the arable land, to four percent. We'd dramatically reduce the human footprint on Earth by building more cities that people can move to. And if these are cities governed by good rules, they can be cities where people are safe from crime, safe from disease and bad sanitation, where people have a chance to get a job. They can get basic utilities like electricity. Their kids can get an education.

So what will it take to get started building the first charter cities, scaling this so we build many more? It would help to have a manual. (Laughter) What university professors could do is write some details that might go into this manual. You wouldn't want to let us run the cities, go out and design them. You wouldn't let academics out in the wild. (Laughter)

But, you could set us to work thinking about questions like, suppose it isn't just Canada that does the deal with Raul Castro. Perhaps Brazil comes in as a participant, and Spain as well. And perhaps Cuba wants to be one of the partners in a four-way joint venture. How would we write the treaty to do that? There is less precedent for that, but that could easily be worked out.

How would we finance this? Turns out Singapore and Hong Kong are cities that made huge gains on the value of the land that they owned when they got started. You could use the gains on the value of the land to pay for things like the police, the courts, but the school system and the health care system too, which make this a more attractive place to live, makes this a place where people have higher incomes -- which, incidentally, makes the land more valuable. So the incentives for the people helping to construct this zone and build it, and set up the basic rules, go very much in the right direction.

So there are many other details like this. How could we have buildings that are low cost and affordable for people who work in a first job, assembling something like an iPhone, but make those buildings energy efficient, and make sure that they are safe, so they don't fall down in an earthquake or a hurricane. Many technical details to be worked out, but those of us who are already starting to pursue these things can already tell that there is no roadblock, there's no impediment, other than a failure of imagination, that will keep us from delivering on a truly global win-win solution.

Let me conclude with this picture. The reason we can be so well off, even though there is so many people on earth, is because of the power of ideas. We can share ideas with other people, and when they discover them, they share with us. It's not like scarce objects, where sharing means we each get less. When we share ideas we all get more. When we think about ideas in that way, we usually think about technologies.

But there is another class of ideas: the rules that govern how we interact with each other; rules like, let's have a tax system that supports a research university that gives away certain kinds of knowledge for free. Let's have a system where we have ownership of land that is registered in a government office, that people can pledge as collateral.

If we can keep innovating on our space of rules, and particularly innovate in the sense of coming up with rules for changing rules, so we don't get stuck with bad rules, then we can keep moving progress forward and truly make the world a better place, so that people like Nelson and his friends don't have to study any longer under the streetlights. Thank you. (Applause)