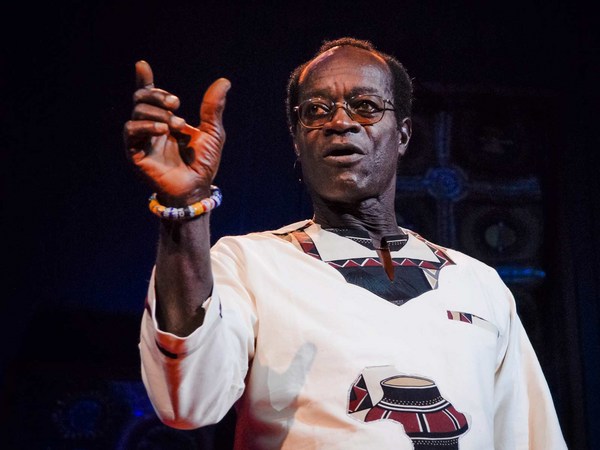

Thank you very much, Chris. Everybody who came up here said they were scared. I don't know if I'm scared, but this is my first time of addressing an audience like this. And I don't have any smart technology for you to look at. There are no slides, so you'll just have to be content with me. (Laughter)

What I want to do this morning is share with you a couple of stories and talk about a different Africa. Already this morning there were some allusions to the Africa that you hear about all the time: the Africa of HIV/AIDS, the Africa of malaria, the Africa of poverty, the Africa of conflict, and the Africa of disasters.

While it is true that those things are going on, there's an Africa that you don't hear about very much. And sometimes I'm puzzled, and I ask myself why. This is the Africa that is changing, that Chris alluded to. This is the Africa of opportunity. This is the Africa where people want to take charge of their own futures and their own destinies. And this is the Africa where people are looking for partnerships to do this. That's what I want to talk about today.

And I want to start by telling you a story about that change in Africa. On 15th of September 2005, Mr. Diepreye Alamieyeseigha, a governor of one of the oil-rich states of Nigeria, was arrested by the London Metropolitan Police on a visit to London. He was arrested because there were transfers of eight million dollars that went into some dormant accounts that belonged to him and his family. This arrest occurred because there was cooperation between the London Metropolitan Police and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission of Nigeria -- led by one of our most able and courageous people: Mr. Nuhu Ribadu. Alamieyeseigha was arraigned in London. Due to some slip-ups, he managed to escape dressed as a woman and ran from London back to Nigeria where, according to our constitution, those in office as governors, president -- as in many countries -- have immunity and cannot be prosecuted. But what happened: people were so outraged by this behavior that it was possible for his state legislature to impeach him and get him out of office.

Today, Alams -- as we call him for short -- is in jail. This is a story about the fact that people in Africa are no longer willing to tolerate corruption from their leaders. This is a story about the fact that people want their resources managed properly for their good, and not taken out to places where they'll benefit just a few of the elite. And therefore, when you hear about the corrupt Africa -- corruption all the time -- I want you to know that the people and the governments are trying hard to fight this in some of the countries, and that some successes are emerging.

Does it mean the problem is over? The answer is no. There's still a long way to go, but that there's a will there. And that successes are being chalked up on this very important fight. So when you hear about corruption, don't just feel that nothing is being done about this -- that you can't operate in any African country because of the overwhelming corruption. That is not the case. There's a will to fight, and in many countries, that fight is ongoing and is being won. In others, like mine, where there has been a long history of dictatorship in Nigeria, the fight is ongoing and we have a long way to go.

But the truth of the matter is that this is going on. The results are showing: independent monitoring by the World Bank and other organizations show that in many instances the trend is downwards in terms of corruption, and governance is improving. A study by the Economic Commission for Africa showed a clear trend upwards in governance in 28 African countries.

And let me say just one more thing before I leave this area of governance. That is that people talk about corruption, corruption. All the time when they talk about it you immediately think about Africa. That's the image: African countries. But let me say this: if Alams was able to export eight million dollars into an account in London -- if the other people who had taken money, estimated at 20 to 40 billion now of developing countries' monies sitting abroad in the developed countries -- if they're able to do this, what is that? Is that not corruption? In this country, if you receive stolen goods, are you not prosecuted? So when we talk about this kind of corruption, let us also think about what is happening on the other side of the globe -- where the money's going and what can be done to stop it. I'm working on an initiative now, along with the World Bank, on asset recovery, trying to do what we can to get the monies that have been taken abroad -- developing countries' moneys -- to get that sent back. Because if we can get the 20 billion dollars sitting out there back, it may be far more for some of these countries than all the aid that is being put together. (Applause)

The second thing I want to talk about is the will for reform. Africans, after -- they're tired, we're tired of being the subject of everybody's charity and care. We are grateful, but we know that we can take charge of our own destinies if we have the will to reform. And what is happening in many African countries now is a realization that no one can do it but us. We have to do it. We can invite partners who can support us, but we have to start. We have to reform our economies, change our leadership, become more democratic, be more open to change and to information.

And this is what we started to do in one of the largest countries on the continent, Nigeria. In fact, if you're not in Nigeria, you're not in Africa. I want to tell you that. (Laughter) One in four sub-Saharan Africans is Nigerian, and it has 140 million dynamic people -- chaotic people -- but very interesting people. You'll never be bored. (Laughter)

What we started to do was to realize that we had to take charge and reform ourselves. And with the support of a leader who was willing, at the time, to do the reforms, we put forward a comprehensive reform program, which we developed ourselves. Not the International Monetary Fund. Not the World Bank, where I worked for 21 years and rose to be a vice president. No one can do it for you. You have to do it for yourself.

We put together a program that would, one: get the state out of businesses it had nothing -- it had no business being in. The state should not be in the business of producing goods and services because it's inefficient and incompetent. So we decided to privatize many of our enterprises. (Applause) We -- as a result, we decided to liberalize many of our markets. Can you believe that prior to this reform -- which started at the end of 2003, when I left Washington to go and take up the post of Finance Minister -- we had a telecommunications company that was only able to develop 4,500 landlines in its entire 30-year history? (Laughter)

Having a telephone in my country was a huge luxury. You couldn't get it. You had to bribe. You had to do everything to get your phone. When President Obasanjo supported and launched the liberalization of the telecommunications sector, we went from 4,500 landlines to 32 million GSM lines, and counting. Nigeria's telecoms market is the second-fastest growing in the world, after China. We are getting investments of about a billion dollars a year in telecoms. And nobody knows, except a few smart people. (Laughter)

The smartest one, first to come in, was the MTN company of South Africa. And in the three years that I was Finance Minister, they made an average of 360 million dollars profit per year. 360 million in a market -- in a country that is a poor country, with an average per capita income just under 500 dollars per capita. So the market is there. When they kept this under wraps, but soon others got to know. Nigerians themselves began to develop some wireless telecommunications companies, and three or four others have come in. But there's a huge market out there, and people don't know about it, or they don't want to know. So privatization is one of the things we've done.

The other thing we've also done is to manage our finances better. Because nobody's going to help you and support you if you're not managing your own finances well. And Nigeria, with the oil sector, had the reputation of being corrupt and not managing its own public finances well. So what did we try to do? We introduced a fiscal rule that de-linked our budget from the oil price. Before we used to just budget on whatever oil we bring in, because oil is the biggest, most revenue-earning sector in the economy: 70 percent of our revenues come from oil. We de-linked that, and once we did it, we began to budget at a price slightly lower than the oil price and save whatever was above that price. We didn't know we could pull it off; it was very controversial. But what it immediately did was that the volatility that had been present in terms of our economic development -- where, even if oil prices were high, we would grow very fast. When they crashed, we crashed. And we could hardly even pay anything, any salaries, in the economy. That smoothened out. We were able to save, just before I left, 27 billion dollars. Whereas -- and this went to our reserves -- when I arrived in 2003, we had seven billion dollars in reserves. By the time I left, we had gone up to almost 30 billion dollars. And as we speak now, we have about 40 billion dollars in reserves due to proper management of our finances. And that shores up our economy, makes it stable.

Our exchange rate that used to fluctuate all the time is now fairly stable and being managed so that business people have a predictability of prices in the economy. We brought inflation down from 28 percent to about 11 percent. And we had GDP grow from an average of 2.3 percent the previous decade to about 6.5 percent now. So all the changes and reforms we were able to make have shown up in results that are measurable in the economy.

And what is more important, because we want to get away from oil and diversify -- and there are so many opportunities in this one big country, as in many countries in Africa -- what was remarkable is that much of this growth came not from the oil sector alone, but from non-oil. Agriculture grew at better than eight percent. As telecoms sector grew, housing and construction, and I could go on and on. And this is to illustrate to you that once you get the macro-economy straightened out, the opportunities in various other sectors are enormous.

We have opportunities in agriculture, like I said. We have opportunities in solid minerals. We have a lot of minerals that no one has even invested in or explored. And we realized that without the proper legislation to make that possible, that wouldn't happen. So we've now got a mining code that is comparable with some of the best in the world. We have opportunities in housing and real estate. There was nothing in a country of 140 million people -- no shopping malls as you know them here. This was an investment opportunity for someone that excited the imagination of people. And now, we have a situation in which the businesses in this mall are doing four times the turnover that they had projected.

So, huge things in construction, real estate, mortgage markets. Financial services: we had 89 banks. Too many not doing their real business. We consolidated them from 89 to 25 banks by requiring that they increase their capital -- share capital. And it went from about 25 million dollars to 150 million dollars. The banks -- these banks are now consolidated, and that strengthening of the banking system has attracted a lot of investment from outside. Barclays Bank of the U.K. is bringing in 500 million. Standard Chartered has brought in 140 million. And I can go on. Dollars, on and on, into the system.

We are doing the same with the insurance sector. So in financial services, a great deal of opportunity. In tourism, in many African countries, a great opportunity. And that's what many people know East Africa for: the wildlife, the elephants, and so on. But managing the tourism market in a way that can really benefit the people is very important.

So what am I trying to say? I'm trying to tell you that there's a new wave on the continent. A new wave of openness and democratization in which, since 2000, more than two-thirds of African countries have had multi-party democratic elections. Not all of them have been perfect, or will be, but the trend is very clear. I'm trying to tell you that since the past three years, the average rate of growth on the continent has moved from about 2.5 percent to about five percent per annum. This is better than the performance of many OECD countries. So it's clear that things are changing.

Conflicts are down on the continent; from about 12 conflicts a decade ago, we are down to three or four conflicts -- one of the most terrible, of course, of which is Darfur. And, you know, you have the neighborhood effect where if something is going on in one part of the continent, it looks like the entire continent is affected. But you should know that this continent is not -- is a continent of many countries, not one country. And if we are down to three or four conflicts, it means that there are plenty of opportunities to invest in stable, growing, exciting economies where there's plenty of opportunity. And I want to just make one point about this investment.

The best way to help Africans today is to help them to stand on their own feet. And the best way to do that is by helping create jobs. There's no issue with fighting malaria and putting money in that and saving children's lives. That's not what I'm saying. That is fine. But imagine the impact on a family: if the parents can be employed and make sure that their children go to school, that they can buy the drugs to fight the disease themselves. If we can invest in places where you yourselves make money whilst creating jobs and helping people stand on their own feet, isn't that a wonderful opportunity? Isn't that the way to go? And I want to say that some of the best people to invest in on the continent are the women. (Applause)

I have a CD here. I'm sorry that I didn't say anything on time. Otherwise, I would have liked you to have seen this. It says, "Africa: Open for Business." And this is a video that has actually won an award as the best documentary of the year. Understand that the woman who made it is going to be in Tanzania, where they're having the session in June. But it shows you Africans, and particularly African women, who against all odds have developed businesses, some of them world-class.

One of the women in this video, Adenike Ogunlesi, making children's clothes -- which she started as a hobby and grew into a business. Mixing African materials, such as we have, with materials from elsewhere. So, she'll make a little pair of dungarees with corduroys, with African material mixed in. Very creative designs, has reached a stage where she even had an order from Wal-Mart. (Laughter) For 10,000 pieces. So that shows you that we have people who are capable of doing.

And the women are diligent. They are focused; they work hard. I could go on giving examples: Beatrice Gakuba of Rwanda, who opened up a flower business and is now exporting to the Dutch auction in Amsterdam each morning and is employing 200 other women and men to work with her. However, many of these are starved for capital to expand, because nobody believes outside of our countries that we can do what is necessary. Nobody thinks in terms of a market. Nobody thinks there's opportunity. But I'm standing here saying that those who miss the boat now, will miss it forever.

So if you want to be in Africa, think about investing. Think about the Beatrices, think about the Adenikes of this world, who are doing incredible things, that are bringing them into the global economy, whilst at the same time making sure that their fellow men and women are employed, and that the children in those households get educated because their parents are earning adequate income.

So I invite you to explore the opportunities. When you go to Tanzania, listen carefully, because I'm sure you will hear of the various openings that there will be for you to get involved in something that will do good for the continent, for the people and for yourselves.

Thank you very much. (Applause)