An undulating sky melds into the landscape, two silhouettes move along a balustraded walkway, and a ghostly figure’s features extend in agony. Since Norwegian artist Edvard Munch created “The Scream” in 1893, it’s become one of the world’s most famous artworks. But why has its cry traveled so far and endured so long?

Munch was born in 1863, one of five children. Tuberculosis devastated Europe throughout the 1800s, killing almost a quarter of all adults. It took Munch’s mother’s life, then his elder sister’s. Soon after, Munch had his own bout of the disease. Another of his sisters experienced mental illness and lived much of her life in an institution. Meanwhile, Munch flitted in and out of school due to illness, often spending days at home, drawing and listening to the ominous stories his father read aloud. A devout Lutheran, his father considered Munch’s artistic ambitions unholy. “I inherited the seeds of madness,” Munch wrote. “The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born.”

Eventually, Munch moved to Berlin, where he frequented creative circles committed to breaking with academic tradition and instead developing their crafts organically. While Munch had trained classically, he began immersing himself in what he called “soul painting”— compositions that prized raw, subjective affect over realistic rendering. “It’s not the chair that should be painted,” he wrote, “but what a person has felt at the sight of it.”

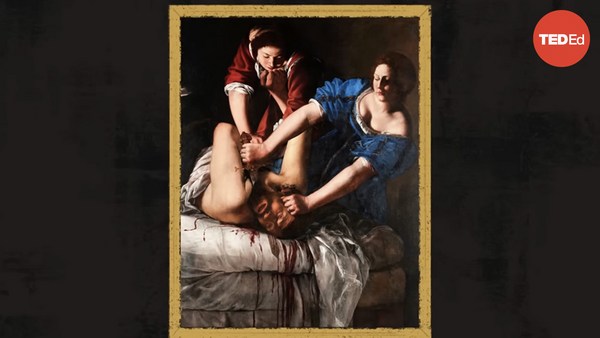

Many of Munch’s works dealt with personal suffering. This may have also led to what certain critics observed as unsympathetic portrayals of women in works where Munch represented them as cruel predators victimizing hapless men. And death often haunted Munch’s compositions— from a skeleton helming a boat to a morbid self-portrait and his sister's final moments to a mother on her deathbed, her child assuming a now-familiar expression. Munch’s art generated controversy— some critics characterizing him as “absolutely demented”— but it also drew acclaim. And what would become his most famous work was just around the corner.

“The Scream” was inspired by a moment that overwhelmed Munch with an acute sense of anguish. In a diary entry marked January 22nd, 1892, Munch described walking with two friends along a fjord overlooking what’s now Oslo at sunset. He leaned against a fence, exhausted, as he saw the sky change suddenly. He described “blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city.” As his friends walked on, Munch wrote, “I stood there trembling with anxiety— and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.” As with other painful experiences, Munch revisited the scene repeatedly.

First, he depicted it with a more recognizably human subject. But the following year, he surrendered it to dramatic, abstracted symbolism, the haunting expression on the figure’s skull-like face meeting the viewer’s gaze directly. On this first version, he added a subtle, wry inscription: “Could only have been painted by a madman!” Based on Munch’s account, many think the figure isn’t emitting the shriek but reacting to it. Munch eventually made four versions of “The Scream”— all on cardboard, two with pastel, two with paint— and he created numerous prints and lithographs. The year following the first “Scream,” he depicted the same setting but featured a collection of despairing faces.

In late 1893, Munch premiered “The Scream” at a solo exhibit in Berlin. The artwork’s bold composition helped fuel the Expressionist movement, which likewise emphasized stark psychological states, mapping the emotional contours of World War I and beyond.

“The Scream” continued its crescendo. When it entered the public domain in the mid-1900s, new renditions and reproductions bolstered its fame. It featured in popular films during the 1990s, and both painted versions of “The Scream” were stolen and recovered in separate heists in 1994 and 2004. Soon enough, it was a widely accepted archetypal symbol for horror and angst. A “Scream”-inspired emoji was eventually implemented. And, considering how to mark hazardous sites so far-off future generations could know to avoid them, the US government has considered using “The Scream” expression. While its myriad cultural influences may not always reflect the personal agony Munch initially rendered, “The Scream” has certainly found a near universal echo.