So, I'm in Chile, in the Atacama desert, sitting in a hotel lobby, because that's the only place that I can get a Wi-Fi connection, and I have this picture up on my screen, and a woman comes up behind me. She says, "Oh, that's beautiful. What is it? Is that Jackson Pollock?" And unfortunately, I can be a little too honest. I said, "No, it's -- it's penguin shit."

(Laughter)

And, you know, "Excuse me!" And I could sense that she thought I was speaking synecdochically.

(Laughter)

So, I said, "No, no, really -- it's penguin shit."

(Laughter)

Because I had just been in the Falkland Islands taking pictures of penguins. This is a Gentoo penguin. And she was still skeptical. So, literally, a few minutes before that, I downloaded this scientific paper about calculations on avian defecation, which is really quite interesting, because it turns out you can model this as something called "Poiseuille flow," and you can learn an awful lot about the physics of the avian rectum. Actually, technically, it's not a rectum. It's called a cloaca.

At this point, she stops me, and she says, "Who are you? Wha -- what do you do?" And I was stuck, because I didn't have any way to describe what I do. And so, in some sense, this talk today is my answer to that. It's a selection of a random bunch of the stuff that I do. And it's very hard for me to make sense of it, so I'm not sure that you can. It's the kind of thing that I sit up late at night thinking about sometimes -- often at four in the morning.

So, some people are afraid of what I do. Some people think I am the nerd Tony Soprano, and in response, I have ordered a bulletproof pocket protector. I'm not sure what these people think, because I don't speak Norsk.

(Laughter)

But I'm not thinking "monsteret" is a good thing. I don't know, you know? So, one of the things that I love to do is travel around the world and look at archaeological sites. Because archaeology gives us an opportunity to study past civilizations, and see where they succeeded and where they failed. Use science to, you know, work backwards and say, "Well, really, what were they thinking?"

And recently, I was in Easter Island, which is an incredibly beautiful place, and an incredibly mysterious place, because no matter where you go in Easter Island, you're struck by these statues, called the moai. The place is 64 square miles. They made, so far as we can tell, 900 of them. Why on Earth? And if you haven't read Jared Diamond's book, "Collapse," I totally recommend that you do. He's got a great chapter about it. Basically, these people committed ecological suicide in order to make more of these. And somewhere along the line, somebody said, "I know! Let's cut down the last tree and commit suicide, because we need more identical statues."

(Laughter)

And, one thing that isn't a mystery, actually, was when I grew up -- because when I was a little kid, I'd seen these pictures -- and I thought, "Well, why that look on the face? Why that brow?" I mean, it's such a powerful thing. Where did they get that inspiration? And then I met Yoyo, who is the native Rapa Nui-an guide, and if you look at Yoyo's face, you kind of figure out where they got it.

There's many mysteries, these statues. Everyone wants to know, how did they make them, how did they transport them? This woman in the foreground is Jo Anne Van Tilberg. She's the leading archaeologist working Easter Island today. And she has studied the statues for 20-some years, and she has detailed records of every single statue. The one on the page here is the same that's up there. One interesting problem is the stone isn't very hard. So, this used to be completely smooth. In fact, in many of the statues, when you excavate them, the backs are totally smooth -- almost glass smooth. But after 1,000 years out in the weather, they look like this.

Jo Anne and I have just embarked on a project to digitize them all, and we're going to do a very high-res digitization, first because it's a way of preserving them. Second, we have these ideas about how you can algorithmically, then, learn a few of the mysteries about them. How long have they been standing in what positions? And maybe, indirectly, get at some of the issues of what caused them to be the way they are. While I was in Easter Island, comet McNaught was there also, so you get a gratuitous picture of a moai with a comet.

I also have an archaeological project going on in Egypt. "Going on" is perhaps a little bit strong. We're trying to get all of the permissions to get everything all set, to get it going. So, I'll talk about it at a future TED. But there's some amazing opportunities in Egypt as well. Another thing I do is I invent stuff. In fact, I design nuclear reactors. Not a joke. This is the conventional nuclear fuel cycle. The red line is what is done in most nuclear reactors. It's called the open fuel cycle. The white lines are what's called an advance fuel cycle, where you reprocess.

Now, this is the normal way it's done. It's got the huge advantage that it does not create carbon pollution. It has a lot of disadvantages: each one of these steps is extremely expensive, it's potentially dangerous and they have the interesting property that the step cannot be performed in anyone's backyard, which is a problem. So, our reactor eliminates these steps, which, if we can actually make it work, is a really cool thing. Now, it's kind of nuts to work on a new nuclear reactor. There's -- no reactor's been even built to an old design, much less a new one, in the United States for 25 years. It's the kind of very high-risk, but potentially very high-return thing that we do.

Changing into a totally different field, we do a lot of stuff in solid state physics, particularly in an area called metamaterials. A metamaterial is an artificial material, which manipulates, in this case, electromagnetic radiation, in a way that you couldn't otherwise. So, this device here is an invisibility cloak. It may not seem that, but if you were a microwave, this is how you would view it. Rays of light -- in this case, microwave light -- come in, and they just squish around the cell, and they come back the other side. Now, you could do that with mirrors from one angle. The cool thing is, this does it from all angles. Metamaterials, unfortunately -- A, it only works on microwave, and B, it doesn't work all that well yet. But metamaterials are an incredibly exciting field. It's -- you know, today I'd like to say it's a zero billion dollar business, but, in fact, it's negative. But some day, some day, maybe it's going to work.

We do a lot of work in biomedical fields. In this case, we're working with a major medical foundation to develop inexpensive ways of diagnosing diseases in developing countries. So, they say the eyes are the windows of the soul -- turns out they're a window to a whole lot more stuff. And these happen to be my eyes, by the way.

Now, I'm also very interested in cooking. While I was at Microsoft, I took a leave of absence and went to a chef school in France. I used to work, also while at Microsoft, at a leading restaurant in Seattle, so I do a lot of cooking. I've been on a team that won the world championship of barbecue. But barbecue's interesting, because it's one of these cult foods like chili, or bouillabaisse. Various parts of the world will have a cult food that people get enormously attached to -- there's tremendous traditions, there's secrecy. And I'm trying to use a very scientific approach. So, this is my latest cooker, and if this looks more complicated than the nuclear reactor, that's because it is. But if you get to play with all those knobs and dials -- and of course, really the controller over there does it all on software -- you can make some terrific ribs.

(Laughter)

This is a high-speed centrifuge. You should all have one in your kitchen, beside your Turbochef. This subjects food to a force about 50,000 times that of normal gravity, and oh boy, does it clarify chicken stock. You would not believe it! I perform a series of ghoulish experiments on food -- in this case, trying to calibrate a mathematical model so that one can predict exactly what the internal cooking times are. It turns out, A, it's useful, and for a geek like me, it's fun. Theory is red, black is experiment. So, I'm either really good at faking it, or this particular model seems to work.

So, another random thing I do is the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI. And you may be familiar with the movie "Contact," which sort of popularized that. It turns out there are real people who go out and search for extraterrestrials in a very scientific way. In fact, almost everybody in the movie is based on a real character, a real person. So, the Jodie Foster character here is actually this woman, Jill Tarter, and Jill has dedicated her life to this. You know, a lot of people risk their lives in a brief act of heroism, which is kind of cool, but Jill has what I call slow heroism. She is risking her professional life on something that her own calculations show may not work for a thousand years -- may not ever. So, I like to support people that are risking their lives.

After the movie came out, of course, there was a lot of interest in SETI. My kids saw the movie, and afterwards they came to me and they said, "So, Dad, so -- so -- that character -- that's Jill, right?" I said, "Oh, yeah, yeah -- absolutely." "And that other person, that's someone -- " I said, "Yes." They said, "Well, you know that creepy rich guy in the movie? Is that you?" I said, "Well, you know, it's just a movie! Come on."

(Laughter)

So, the SETI Institute, with a little bit of help from me, and a lot of help from Paul Allen and a variety of other people, is building a dedicated radio telescope in Hat Creek, California, so they can do this SETI work. Now, I travel a lot, and I change cell phones a lot, and the one person who always gets updated on all my cell phones and pagers and everything else is Jill, because I really don't want to miss "the call."

(Laughter)

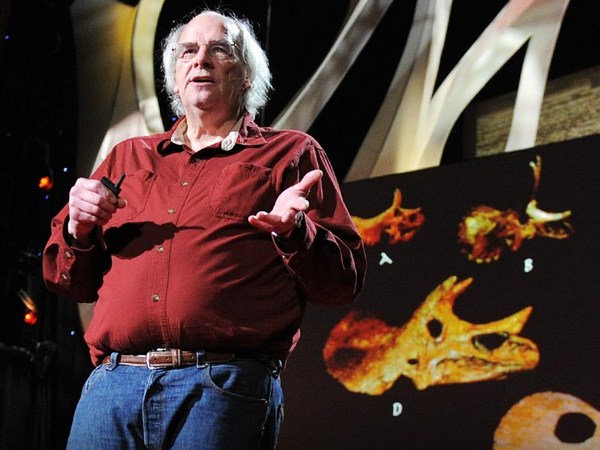

I mean, can you imagine? E.T.'s phoning home, and I'm not, like, there? You know, horrible! So, I do a lot of work on dinosaurs. I'm known to TEDsters as the guy that has sex with dinosaurs. And I resemble that remark. I'm going to talk about a different aspect of dinosaurs, which is the finding of them. Now, to find dinosaurs, you hike around in horrible conditions looking for a dinosaur. It sounds really dumb, but that's what it is. It's horrible conditions, because wherever you have nice weather, plants grow, and you don't get any erosion, and you don't see any dinosaurs. So, you always find dinosaurs in deserts or badlands, areas that have very little plant growth and have flash floods in the spring. You know, skiers pray for snow? Paleontologists pray for erosion.

So, you hike around and -- this is after you dig them up, they look like this. You hike around, you see something like this. Now, this is something I found, so look at it very closely here. You've got this bentonite clay, which is -- sort of swells up and expands. And there's some stuff poking out. So, you look at that, and you look up close, and you say, "Well, gee, that's kind of interesting. What are all of these pieces?" Well, if you look closely, you can recognize, actually, from the shape, that these are skull fragments. And then when you look at this, you say, "That's a tooth. It's a big tooth." It's about the size of a banana. It has a big serration on the edge. This is what Tyrannosaurus rex looks like in the ground. And this is what it's like to find a Tyrannosaurus rex, which I was lucky enough to do a few years ago.

Now, this is what Tyrannosaurus rex looks like in my living room. Not the same one, actually. This is a cast, which I had bought, and then, after buying the cast, I found my own, and I don't have room for two. You know. So, the thing that's wonderful for me about finding dinosaurs is that it is both an intellectual thing, because you're trying to reconstruct the environment of millions of years ago. It's something that can inform all sorts of science in unexpected ways. The study of dinosaurs led to the realization that there's a problem with asteroid impact, for example. The study of dinosaurs may, literally, one day save the planet.

Study of the ancient climate is very important. In fact, the Mesozoic, when dinosaurs lived, had much higher CO2 than today, was much warmer than today, and is one of the interesting proof points for the effects of CO2 on climate. But, besides being intellectually and scientifically interesting, it's also very different than the other things I do, because you get to hike around in the badlands. This is actually what most dinosaur research looks like. This is one of my papers: "A pygostyle from a non-avian theropod." It's not as gripping as dinosaur sex, so we're not going to go into it further.

Now, I'm also really big on photography. I travel all over the world taking pictures -- some of them good, most of them not. These days, bits are cheap. Unfortunately, that means you've got to spend more time sorting through them. Here's a picture I took in the Falkland Islands of king penguins on a beach. Here's a picture I took in Alaska, a few years ago, of Orcas. I'd gone up to photograph Orcas, and we had looked for a week, and we hadn't seen a damn Orca. And the last day, the sun comes out, the Orcas come, they're right by the boat. It's fantastic. And I get lots of pictures like this. Then, a little bit later, I start getting some pictures like this. Now, to a human audience, I need to explain that if Penthouse magazine had a marine mammal edition, this would be the centerfold. It's true. So, there's more and more activity near the boat, and all of a sudden somebody shouts, "What's that in the water?" I said, "Well, I think that's what you call a free willy."

(Laughter)

There's a variety of things you can learn from watching whales have sex.

(Laughter) The first thing you learn is the overwhelming importance of hands. They don't have them.

(Laughter)

I think Paul Simon is in the audience, and he has -- he may not realize it, but he wrote a song all about whale sex, "Slip-Slidin' Away." That's kind of what it's like. The other interesting thing that I learned about whale sex: they curl their toes too.

(Laughter)

So -- where do you go putting all of these disparate pieces together? You know, there's a tremendous amount of wisdom in finding a great thing, passion in life, and focusing all your energy on it, and I've never been able to do that. I just -- you know, because, yes, I'll focus passion on something, but then there will be something else, and then there's something else again. And for a long time I fought this, and I thought, "Well, gee, I really ought to buckle down." And you know, when I was at Microsoft, that was so engrossing, and the whole industry was expanding so much, that it did tend to crowd out most of the other things in my life.

But ultimately, I decided that what I really ought to do is not fight being who I am, but embrace it. And say, "Yeah, you know, I -- this whole talk has been a mile wide and an inch deep, but that's really what works for me." And regardless of whether it's nuclear reactors or metamaterials or whale sex, the common -- or lowest common denominator -- is me. That's it, thank you.

(Applause)