I'm delighted to be here. I'm honored by the invitation, and thanks. I would love to talk about stuff that I'm interested in, but unfortunately, I suspect that what I'm interested in won't interest many other people. First off, my badge says I'm an astronomer. I would love to talk about my astronomy, but I suspect that the number of people who are interested in radiative transfer in non-gray atmospheres and polarization of light in Jupiter's upper atmosphere are the number of people who'd fit in a bus shelter. So I'm not going to talk about that. (Laughter)

It would be just as much fun to talk about some stuff that happened in 1986 and 1987, when a computer hacker is breaking into our systems over at Lawrence Berkeley Labs. And I caught the guys, and they turned out to be working for what was then the Soviet KGB, and stealing information and selling it. And I'd love to talk about that -- and it'd be fun -- but, 20 years later ... I find computer security, frankly, to be kind of boring. It's tedious. I'm --

The first time you do something, it's science. The second time, it's engineering. A third time, it's just being a technician. I'm a scientist. Once I do something, I do something else. So, I'm not going to talk about that. Nor am I going to talk about what I think are obvious statements from my first book, "Silicon Snake Oil," or my second book, nor am I going to talk about why I believe computers don't belong in schools.

I feel that there's a massive and bizarre idea going around that we have to bring more computers into schools. My idea is: no! No! Get them out of schools, and keep them out of schools. And I'd love to talk about this, but I think the argument is so obvious to anyone who's hung around a fourth grade classroom that it doesn't need much talking about -- but I guess I may be very wrong about that, and everything else that I've said. So don't go back and read my dissertation. It probably has lies in it as well.

Having said that, I outlined my talk about five minutes ago. (Laughter) And if you look at it over here, the main thing I wrote on my thumb was the future. I'm supposed to talk about the future, yes? Oh, right. And my feeling is, asking me to talk about the future is bizarre, because I've got gray hair, and so, it's kind of silly for me to talk about the future. In fact, I think that if you really want to know what the future's going to be, if you really want to know about the future, don't ask a technologist, a scientist, a physicist. No! Don't ask somebody who's writing code.

No, if you want to know what society's going to be like in 20 years, ask a kindergarten teacher. They know. In fact, don't ask just any kindergarten teacher, ask an experienced one. They're the ones who know what society is going to be like in another generation. I don't. Nor, I suspect, do many other people who are talking about what the future will bring. Certainly, all of us can imagine these cool new things that are going to be there. But to me, things aren't the future. What I ask myself is, what's society is going to be like, when the kids today are phenomenally good at text messaging and spend a huge amount of on-screen time, but have never gone bowling together?

Change is happening, and the change that is happening is not one that is in software. But that's not what I'm going to talk about. I'd love to talk about it, it'd be fun, but I want to talk about what I'm doing now. What am I doing now? Oh -- the other thing that I think I'd like to talk about is right over here. Right over here. Is that visible? What I'd like to talk about is one-sided things. I would dearly love to talk about things that have one side. Because I love Mobius loops. I not only love Mobius loops, but I'm one of the very few people, if not the only person in the world, that makes Klein bottles. Right away, I hope that all of your eyes glaze over. This is a Klein bottle. For those of you in the audience who know, you roll your eyes and say, yup, I know all about it. It's one sided. It's a bottle whose inside is its outside. It has zero volume. And it's non-orientable. It has wonderful properties. If you take two Mobius loops and sew their common edge together, you get one of these, and I make them out of glass. And I'd love to talk to you about this, but I don't have much in the way of ... things to say because -- (Laughter)

(Chris Anderson: I've got a cold.)

However, the "D" in TED of course stands for design. Just two weeks ago I made -- you know, I've been making small, medium and big Klein bottles for the trade. But what I've just made -- and I'm delighted to show you, first time in public here. This is a Klein bottle wine bottle, which, although in four dimensions it shouldn't be able to hold any fluid at all, it's perfectly capable of doing so because our universe has only three spatial dimensions. And because our universe is only three spatial dimensions, it can hold fluids. So it's highly -- that one's the cool one. That was a month of my life. But although I would love to talk about topology with you, I'm not going to. (Laughter)

Instead, I'm going to mention my mom, who passed away last summer. Had collected photographs of me, as mothers will do. Could somebody put this guy up? And I looked over her album and she had collected a picture of me, standing -- well, sitting -- in 1969, in front of a bunch of dials. And I looked at it, and said, oh my god, that was me, when I was working at the electronic music studio! As a technician, repairing and maintaining the electronic music studio at SUNY Buffalo. And wow! Way back machine. And I said to myself, oh yeah! And it sent me back.

Soon after that, I found in another picture that she had, a picture of me. This guy over here of course is me. This man is Robert Moog, the inventor of the Moog synthesizer, who passed away this past August. Robert Moog was a generous, kind person, extraordinarily competent engineer. A musician who took time from his life to teach me, a sophomore, a freshman at SUNY Buffalo. He'd come up from Trumansburg to teach me not just about the Moog synthesizer, but we'd be sitting there -- I'm studying physics at the time. This is 1969, 70, 71. We're studying physics, I'm studying physics, and he's saying, "That's a good thing to do. Don't get caught up in electronic music if you're doing physics." Mentoring me. He'd come up and spend hours and hours with me. He wrote a letter of recommendation for me to get into graduate school. In the background, my bicycle. I realize that this picture was taken at a friend's living room. Bob Moog came by and hauled a whole pile of equipment to show Greg Flint and I things about this. We sat around talking about Fourier transforms, Bessel functions, modulation transfer functions, stuff like this. Bob's passing this past summer has been a loss to all of us. Anyone who's a musician has been profoundly influenced by Robert Moog. (Applause) And I'll just say what I'm about to do. What I'm about to do -- I hope you can recognize that there's a distorted sine wave, almost a triangular wave upon this Hewlett-Packard oscilloscope.

Oh, cool. I can get to this place over here, right? Kids. Kids is what I'm going to talk about -- is that okay? It says kids over here, that's what I'd like to talk about. I've decided that, for me at least, I don't have a big enough head. So I think locally and I act locally. I feel that the best way I can help out anything is to help out very, very locally. So Ph.D. this, and degree there, and the yadda yadda. I was talking about this stuff to some schoolteachers about a year ago. And one of them, several of them would come up to me and say, "Well, how come you ain't teaching?" And I said, "Well, I've taught graduate -- I've had graduate students, I've taught undergraduate classes." No, they said, "If you're so into kids and all this stuff, how come you ain't over here on the front lines? Put your money where you mouth is."

Is true. Is true. I teach eighth-grade science four days a week. Not just showing up every now and then. No, no, no, no, no. I take attendance. I take lunch hour. (Applause) This is not -- no, no, no, this is not claps. I strongly suggest that this is a good thing for each of you to do. Not just show up to class every now and then. Teach a solid week. Okay, I'm teaching three-quarters time, but good enough. One of the things that I've done for my science students is to tell them, "Look, I'm going to teach you college-level physics. No calculus, I'll cut out that. You won't need to know trig. But you will need to know eighth-grade algebra, and we're going to do serious experiments. None of this open-to-chapter-seven-and-do-all-the-odd-problem-sets. We're going to be doing genuine physics." And that's one of the things I thought I'd do right now. (High-pitched tone)

Oh, before I even turn that on, one of the things that we did about three weeks ago in my class -- this is through the lens, and one of the things we used a lens for was to measure the speed of light. My students in El Cerrito -- with my help, of course, and with the help of a very beat up oscilloscope -- measured the speed of light. We were off by 25 percent. How many eighth graders do you know of who have measured the speed of light? In addition to that, we've measured the speed of sound. I'd love to measure the speed of light here. I was all set to do it and I was thinking, "Aw man," I was just going to impose upon the powers that be, and measure the speed of light. And I'm all set to do it. I'm all set to do it, but then it turns out that to set up here, you have like 10 minutes to set up! And there's no time to do it. So, next time, maybe, I'll measure the speed of light!

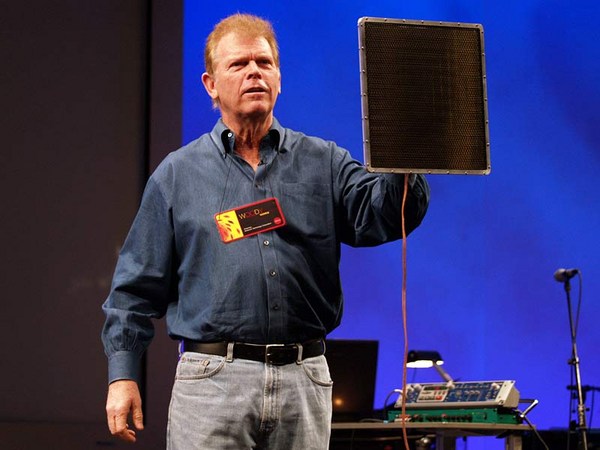

But meanwhile, let's measure the speed of sound! Well, the obvious way to measure the speed of sound is to bounce sound off something and look at the echo. But, probably -- one of my students, Ariel [unclear], said, "Could we measure the speed of light using the wave equation?" And all of you know the wave equation is the frequency times the wavelength of any wave ... is a constant. When the frequency goes up, the wavelength comes down. Wavelength goes up, frequency goes down. So, if we have a wave here -- over here, that's what's interesting -- as the pitch goes up, things get closer, pitch goes down, things stretch out. Right? This is simple physics. All of you know this from eighth grade, remember? What they didn't tell you in physics -- in eighth-grade physics -- but they should have, and I wish they had, was that if you multiply the frequency times the wavelength of sound or light, you get a constant. And that constant is the speed of sound. So, in order to measure the speed of sound, all I've got to do is know its frequency. Well, that's easy. I've got a frequency counter right here. Set it up to around A, above A, above A. There's an A, more or less. Now, so I know the frequency. It's 1.76 kilohertz. I measure its wavelength. All I need now is to flip on another beam, and the bottom beam is me talking, right? So anytime I talk, you'd see it on the screen. I'll put it over here, and as I move this away from the source, you'll notice the spiral. The slinky moves. We're going through different nodes of the wave, coming out this way. Those of you who are physicists, I hear you rolling your eyes, but bear with me. (Laughter)

To measure the wavelength, all I need to do is measure the distance from here -- one full wave -- over to here. From here to here is the wavelength of sound. So, I'll put a measuring tape here, measuring tape here, move it back over to here. I've moved the microphone 20 centimeters. 0.2 meters from here, back to here, 20 centimeters. OK, let's go back to Mr. Elmo. And we'll say the frequency is 1.76 kilohertz, or 1760. The wavelength was 0.2 meters. Let's figure out what this is. (Laughter) (Applause) 1.76 times 0.2 over here is 352 meters per second. If you look it up in the book, it's really 343. But, here with kludgy material, and lousy drink -- we've been able to measure the speed of sound to -- not bad. Pretty good.

All of which comes to what I wanted to say. Go back to this picture of me a million years ago. It was 1971, the Vietnam War was going on, and I'm like, "Oh my God!" I'm studying physics: Landau, Lipschitz, Resnick and Halliday. I'm going home for a midterm. A riot's going on on campus. There's a riot! Hey, Elmo's done: off. There's a riot going on on campus, and the police are chasing me, right? I'm walking across campus. Cop comes and looks at me and says, "You! You're a student." Pulls out a gun. Goes boom! And a tear gas canister the size of a Pepsi can goes by my head. Whoosh! I get a breath of tear gas and I can't breathe. This cop comes after me with a rifle. He wants to clunk me over the head! I'm saying, "I got to clear out of here!" I go running across campus quick as I can. I duck into Hayes Hall. It's one of these bell-tower buildings. The cop's chasing me. Chasing me up the first floor, second floor, third floor. Chases me into this room. The entranceway to the bell tower. I slam the door behind me, climb up, go past this place where I see a pendulum ticking. And I'm thinking, "Oh yeah, the square root of the length is proportional to its period." (Laughter)

I keep climbing up, go back. I go to a place where a dowel splits off. There's a clock, clock, clock, clock. The time's going backwards because I'm inside of it. I'm thinking of Lorenz contractions and Einsteinian relativity. I climb up, and there's this place, way in the back, that you climb up this wooden ladder. I pop up the top, and there's a cupola. A dome, one of these ten-foot domes. I'm looking out and I'm seeing the cops bashing students' heads, shooting tear gas, and watching students throwing bricks. And I'm asking, "What am I doing here? Why am I here?" Then I remember what my English teacher in high school said. Namely, that when they cast bells, they write inscriptions on them. So, I wipe the pigeon manure off one of the bells, and I look at it. I'm asking myself, "Why am I here?"

So, at this time, I'd like to tell you the words inscribed upon the Hayes Hall tower bells: "All truth is one. In this light, may science and religion endeavor here for the steady evolution of mankind, from darkness to light, from narrowness to broad-mindedness, from prejudice to tolerance. It is the voice of life, which calls us to come and learn." Thank you very much.