The cry of the crowd. The roar of a lion. The clash of metal. Starting in 80 CE these sounds rang through the stands of the Colosseum. On hundreds of days a year, over 50,000 residents of Rome and visitors from across the Roman Empire would fill the stadiums’ four stories to see gladiators duel, animals fight, and chariots race around the arena. And for the grand finale, water poured into the arena basin, submerging the stage for the greatest spectacle of all: staged naval battles.

The Romans’ epic, mock maritime encounters, called naumachiae, started during Julius Caesar’s reign in the first century BC, over a hundred years before the Colosseum was built. They were held alongside other aquatic spectacles on natural and artificial bodies of water around Rome up through Emperor Flavius Vespasian, who began building the Colosseum in 70 CE on the site of a former lake. The Colosseum was intended to be a symbol of Rome’s power in the ancient world, and what better way to display that power than a body of water that could drain and refill at the Emperor’s command?

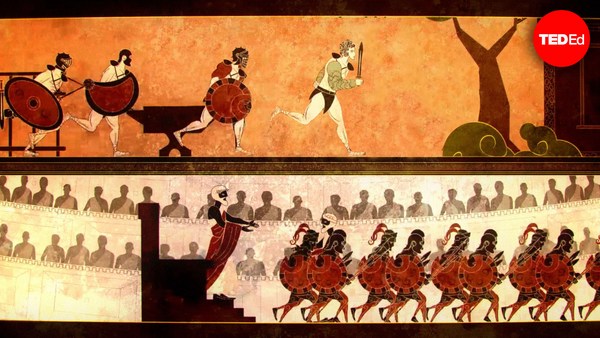

Vespasian’s son Flavius Titus fulfilled his father’s dream in 80 CE when he used war spoils to finish the Colosseum– or as it was known at the time, the Flavian Amphitheater. The grand opening was celebrated with 100 days of pageantry and gladiatorial games, setting the precedent for programming that included parades, musical performances, public executions, and of course, gladiatorial combat. Unlike the games in smaller amphitheaters funded by wealthy Romans, these lavish displays of Imperial power were financed by the Emperor. Parades of exotic animals, theatrical performances, and the awe-inspiring naumachiae were all designed to bolster faith in the god-like Emperor, who would be declared a god after his own death.

It’s still a mystery how engineers flooded the arena to create this aquatic effect. Some historians believe a giant aqueduct was diverted into the arena. Others think the system of chambers and sluice gates used to drain the arena, were also used to fill it. These chambers could’ve been filled with water prior to the event and then opened to submerge the stage under more than a million gallons of water, to create a depth of five feet.

But even with all that water, the Romans had to construct miniature boats with special flat bottoms that wouldn’t scrape the Colosseum floor. These boats ranged from 7 to 15 meters long, and were built to look like vessels from famous encounters. During a battle, dozens of these ships would float around the arena, crewed by gladiators dressed as the opposing sides of the recreated battle. These warriors would duel across ships; boarding them, fighting, drowning, and incapacitating their foes until only one faction was left standing.

Fortunately, not every watery display told such a gruesome story. In some of these floodings, a submerged stage allowed chariot drivers to glide across the water as though they were Triton, making waves as he piloted his chariot on the sea. Animals walked on water, myths were re-enacted by condemned prisoners, and at night, nude synchronized swimmers would perform by torchlight.

But the Colosseum’s aquatic age didn’t last forever. The naval battles proved so popular they were given their own nearby lake by Emperor Domitian in the early 90s CE. The larger lake proved even better for naumachiae, and the Colosseum soon gained a series of underground animal cages and trap doors that didn’t allow for further flooding. But for a brief time, the Flavian Emperors controlled the tides of war and water in a spectacular show of power.