Sarge Salman: All the way from Los Altos Hills, California, Mr. Henry Evans.

(Applause)

Henry Evans: Hello. My name is Henry Evans, and until August 29, 2002, I was living my version of the American dream. I grew up in a typical American town near St. Louis. My dad was a lawyer. My mom was a homemaker. My six siblings and I were good kids, but caused our fair share of trouble. After high school, I left home to study and learn more about the world. I went to Notre Dame University and graduated with degrees in accounting and German, including spending a year of study in Austria. Later on, I earned an MBA at Stanford. I married my high school sweetheart, Jane. I am lucky to have her. Together, we raised four wonderful children. I worked and studied hard to move up the career ladder, eventually becoming a chief financial officer in Silicon Valley, a job I really enjoyed. My family and I bought our first and only home on December 13, 2001, a fixer-upper in a beautiful spot of Los Altos Hills, California, from where I am speaking to you now.

We were looking forward to rebuilding it, but eight months after we moved in, I suffered a stroke-like attack caused by a birth defect. Overnight, I became a mute quadriplegic at the ripe old age of 40. It took me several years, but with the help of an incredibly supportive family, I finally decided life was still worth living. I became fascinated with using technology to help the severely disabled. Head tracking devices sold commercially by the company Madentec convert my tiny head movements into cursor movements, and enable my use of a regular computer. I can surf the web, exchange email with people, and routinely destroy my friend Steve Cousins in online word games. This technology allows me to remain engaged, mentally active, and feel like I am a part of the world.

One day, I was lying in bed watching CNN, when I was amazed by Professor Charlie Kemp of the Healthcare Robotics Lab at Georgia Tech demonstrating a PR2 robot. I emailed Charlie and Steve Cousins of Willow Garage, and we formed the Robots for Humanity project. For about two years, Robots for Humanity developed ways for me to use the PR2 as my body surrogate. I shaved myself for the first time in 10 years. From my home in California, I shaved Charlie in Atlanta. (Laughter) I handed out Halloween candy. I opened my refrigerator on my own. I began doing tasks around the house. I saw new and previously unthinkable possibilities to live and contribute, both for myself and others in my circumstance.

All of us have disabilities in one form or another. For example, if either of us wants to go 60 miles an hour, both of us will need an assistive device called a car. Your disability doesn't make you any less of a person, and neither does mine. By the way, check out my sweet ride. (Laughter) Since birth, we have both suffered from the inability to fly on our own.

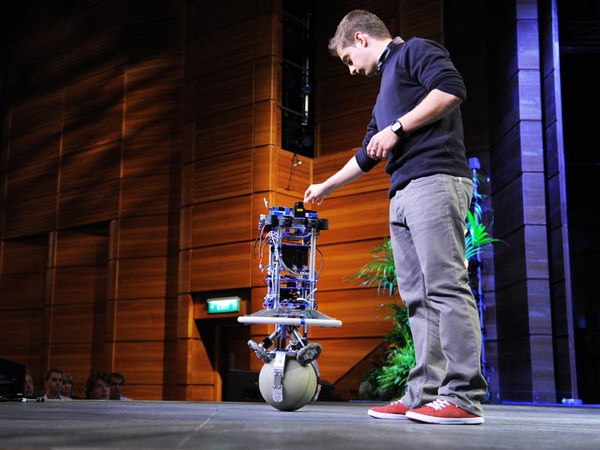

Last year, Kaijen Hsiao of Willow Garage connected with me Chad Jenkins. Chad showed me how easy it is to purchase and fly aerial drones. It was then I realized that I could also use an aerial drone to expand the worlds of bedridden people through flight, giving a sense of movement and control that is incredible. Using a mouse cursor I control with my head, these web interfaces allow me to see video from the robot and send control commands by pressing buttons in a web browser. With a little practice, I became good enough with this interface to drive around my home on my own. I could look around our garden and see the grapes we are growing. I inspected the solar panels on our roof. (Laughter) One of my challenges as a pilot is to land the drone on our basketball hoop. I went even further by seeing if I could use a head-mounted display, the Oculus Rift, as modified by Fighting Walrus, to have an immersive experience controlling the drone. With Chad's group at Brown, I regularly fly drones around his lab several times a week, from my home 3,000 miles away. All work and no fun makes for a dull quadriplegic, so we also find time to play friendly games of robot soccer. (Laughter) I never thought I would be able to casually move around a campus like Brown on my own. I just wish I could afford the tuition. (Laughter)

Chad Jenkins: Henry, all joking aside, I bet all of these people here would love to see you fly this drone from your bed in California 3,000 miles away.

(Applause)

Okay, Henry, have you been to D.C. lately?

(Laughter)

Are you excited to be at TEDxMidAtlantic?

(Laughter) (Applause)

Can you show us how excited you are?

(Laughter)

All right, big finish. Can you show us how good of a pilot you are?

(Applause)

All right, we still have a little ways to go with that, but I think it shows the promise.

What makes Henry's story amazing is it's about understanding Henry's needs, understanding what people in Henry's situation need from technology, and then also understanding what advanced technology can provide, and then bringing those two things together for use in a wise and responsible way. What we're trying to do is democratize robotics, so that anybody can be a part of this. We're providing affordable, off-the-shelf robot platforms such as the A.R. drone, 300 dollars, the Suitable Technologies beam, only 17,000 dollars, along with open-source robotics software so that you can be a part of what we're trying to do. And our hope is that, by providing these tools, that you'll be able to think of better ways to provide movement for the disabled, to provide care for our aging population, to help better educate our children, to think about what the new types of middle class jobs could be for the future, to both monitor and protect our environment, and to explore the universe.

Back to you, Henry.

HE: Thank you, Chad.

With this drone setup, we show the potential for bedridden people to once again be able to explore the outside world, and robotics will eventually provide a level playing field where one is only limited by their mental acuity and imagination, where the disabled are able to perform the same activities as everyone else, and perhaps better, and technology will even allow us to provide an outlet for many people who are presently considered vegetables. One hundred years ago, I would have been treated like a vegetable. Actually, that's not true. I would have died.

It is up to us, all of us, to decide how robotics will be used, for good or for evil, for simply replacing people or for making people better, for allowing us to do and enjoy more.

Our goal for robotics is to unlock everyone's mental power by making the world more physically accessible to people such as myself and others like me around the globe. With the help of people like you, we can make this dream a reality.

Thank you.

(Applause)