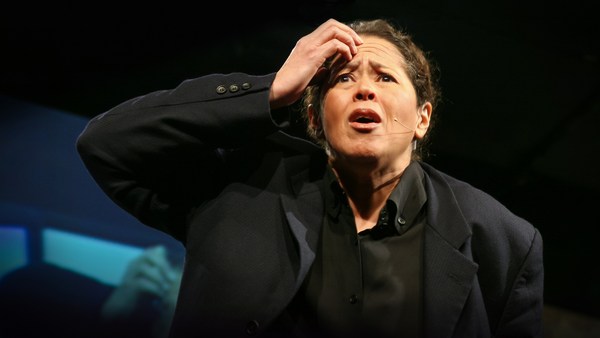

So I understand that this meeting was planned, and the slogan was From Was to Still. And I am illustrating Still. Which, of course, I am not agreeing with because, although I am 94, I am not still working. And anybody who asks me, "Are you still doing this or that?" I don't answer because I'm not doing things still, I'm doing it like I always did. I still have -- or did I use the word still? I didn't mean that.

(Laughter)

I have my file which is called To Do. I have my plans. I have my clients. I am doing my work like I always did. So this takes care of my age. I want to show you my work so you know what I am doing and why I am here. This was about 1925. All of these things were made during the last 75 years.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

But, of course, I'm working since 25, doing more or less what you see here. This is Castleton China. This was an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. This is now for sale at the Metropolitan Museum. This is still at the Metropolitan Museum now for sale. This is a portrait of my daughter and myself.

(Applause)

These were just some of the things I've made. I made hundreds of them for the last 75 years. I call myself a maker of things. I don't call myself an industrial designer because I'm other things. Industrial designers want to make novel things. Novelty is a concept of commerce, not an aesthetic concept. The industrial design magazine, I believe, is called "Innovation." Innovation is not part of the aim of my work. Well, makers of things: they make things more beautiful, more elegant, more comfortable than just the craftsmen do. I have so much to say. I have to think what I am going to say. Well, to describe our profession otherwise, we are actually concerned with the playful search for beauty. That means the playful search for beauty was called the first activity of Man. Sarah Smith, who was a mathematics professor at MIT, wrote, "The playful search for beauty was Man's first activity -- that all useful qualities and all material qualities were developed from the playful search for beauty." These are tiles. The word, "playful" is a necessary aspect of our work because, actually, one of our problems is that we have to make, produce, lovely things throughout all of life, and this for me is now 75 years.

So how can you, without drying up, make things with the same pleasure, as a gift to others, for so long? The playful is therefore an important part of our quality as designer. Let me tell you some about my life. As I said, I started to do these things 75 years ago. My first exhibition in the United States was at the Sesquicentennial exhibition in 1926 -- that the Hungarian government sent one of my hand-drawn pieces as part of the exhibit. My work actually took me through many countries, and showed me a great part of the world. This is not that they took me -- the work didn't take me -- I made the things particularly because I wanted to use them to see the world. I was incredibly curious to see the world, and I made all these things, which then finally did take me to see many countries and many cultures. I started as an apprentice to a Hungarian craftsman, and this taught me what the guild system was in Middle Ages.

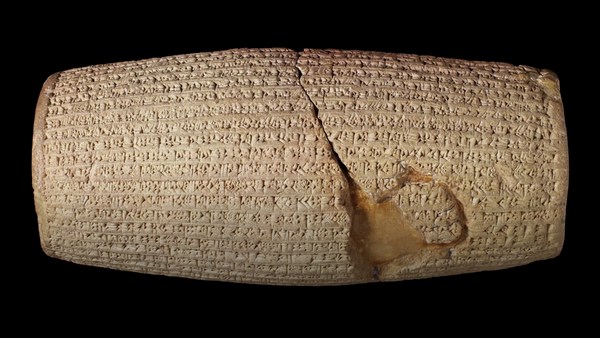

The guild system: that means when I was an apprentice, I had to apprentice myself in order to become a pottery master. In my shop where I studied, or learned, there was a traditional hierarchy of master, journeyman and learned worker, and apprentice, and I worked as the apprentice. The work as an apprentice was very primitive. That means I had to actually learn every aspect of making pottery by hand. We mashed the clay with our feet when it came from the hillside. After that, it had to be kneaded. It had to then go in, kind of, a mangle. And then finally it was prepared for the throwing. And there I really worked as an apprentice. My master took me to set ovens because this was part of oven-making, oven-setting, in the time. And finally, I had received a document that I had accomplished my apprenticeship successfully, that I had behaved morally, and this document was given to me by the Guild of Roof-Coverers, Rail-Diggers, Oven-Setters, Chimney Sweeps and Potters.

(Laughter)

I also got at the time a workbook which explained my rights and my working conditions, and I still have that workbook. First I set up a shop in my own garden, and made pottery which I sold on the marketplace in Budapest. And there I was sitting, and my then-boyfriend -- I didn't mean it was a boyfriend like it is meant today -- but my boyfriend and I sat at the market and sold the pots. My mother thought that this was not very proper, so she sat with us to add propriety to this activity.

(Laughter)

However, after a while there was a new factory being built in Budapest, a pottery factory, a large one. And I visited it with several ladies, and asked all sorts of questions of the director. Then the director asked me, why do you ask all these questions? I said, I also have a pottery. So he asked me, could he please visit me, and then finally he did, and explained to me that what I did now in my shop was an anachronism, that the industrial revolution had broken out, and that I rather should join the factory. There he made an art department for me where I worked for several months. However, everybody in the factory spent his time at the art department. The director there said there were several women casting and producing my designs now in molds, and this was sold also to America.

I remember that it was quite successful. However, the director, the chemist, model maker -- everybody -- concerned himself much more with the art department -- that means, with my work -- than making toilets, so finally they got a letter from the center, from the bank who owned the factory, saying, make toilet-setting behind the art department, and that was my end. So this gave me the possibility because now I was a journeyman, and journeymen also take their satchel and go to see the world. So as a journeyman, I put an ad into the paper that I had studied, that I was a down-to-earth potter's journeyman and I was looking for a job as a journeyman. And I got several answers, and I accepted the one which was farthest from home and practically, I thought, halfway to America.

And that was in Hamburg. Then I first took this job in Hamburg, at an art pottery where everything was done on the wheel, and so I worked in a shop where there were several potters. And the first day, I was coming to take my place at the turntable -- there were three or four turntables -- and one of them, behind where I was sitting, was a hunchback, a deaf-mute hunchback, who smelled very bad. So I doused him in cologne every day, which he thought was very nice, and therefore he brought bread and butter every day, which I had to eat out of courtesy. The first day I came to work in this shop there was on my wheel a surprise for me. My colleagues had thoughtfully put on the wheel where I was supposed to work a very nicely modeled natural man's organs. (Laughter) After I brushed them off with a hand motion, they were very -- I finally was now accepted, and worked there for some six months. This was my first job. If I go on like this, you will be here till midnight.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

So I will try speed it up a little

(Laughter)

Moderator: Eva, we have about five minutes.

(Laughter)

Eva Zeisel: Are you sure?

Moderator: Yes, I am sure.

EZ: Well, if you are sure, I have to tell you that within five minutes I will talk very fast. And actually, my work took me to many countries because I used my work to fill my curiosity. And among other things, other countries I worked, was in the Soviet Union, where I worked from '32 to '37 -- actually, to '36. I was finally there, although I had nothing to do -- I was a foreign expert. I became art director of the china and glass industry, and eventually under Stalin's purges -- at the beginning of Stalin's purges, I didn't know that hundreds of thousands of innocent people were arrested. So I was arrested quite early in Stalin's purges, and spent 16 months in a Russian prison. The accusation was that I had successfully prepared an Attentat on Stalin's life. This was a very dangerous accusation. And if this is the end of my five minutes, I want to tell you that I actually did survive, which was a surprise. But since I survived and I'm here, and since this is the end of the five minutes, I will --

Moderator: Tell me when your last trip to Russia was. Weren't you there recently?

EZ: Oh, this summer, in fact, the Lomonosov factory was bought by an American company, invited me. They found out that I had worked in '33 at this factory, and they came to my studio in Rockland County, and brought the 15 of their artists to visit me here. And they invited myself to come to the Russian factory last summer, in July, to make some dishes, design some dishes. And since I don't like to travel alone, they also invited my daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter, so we had a lovely trip to see Russia today, which is not a very pleasant and happy view. Here I am now, if this is the end? Thank you.

(Applause)