A mosquito lands on your arm, injects its chemicals into your skin, and begins to feed. You wouldn’t even know it was there, if not for the red lump that appears, accompanied by a telltale itch. It’s a nuisance, but that bump is an important signal that you’re protected by your immune system, your body’s major safeguard against infection, illness, and disease.

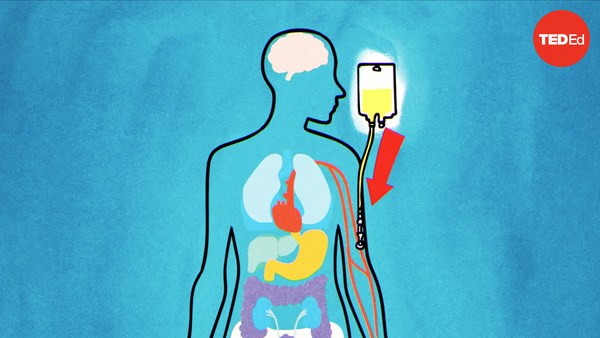

This system is a vast network of cells, tissues, and organs that coordinate your body’s defenses against any threats to your health. Without it, you’d be exposed to billions of bacteria, viruses, and toxins that could make something as minor as a paper cut or a seasonal cold fatal.

The immune system relies on millions of defensive white blood cells, also known as leukocytes, that originate in our bone marrow. These cells migrate into the bloodstream and the lymphatic system, a network of vessels which helps clear bodily toxins and waste. Our bodies are teeming with leukocytes: there are between 4,000 and 11,000 in every microliter of blood.

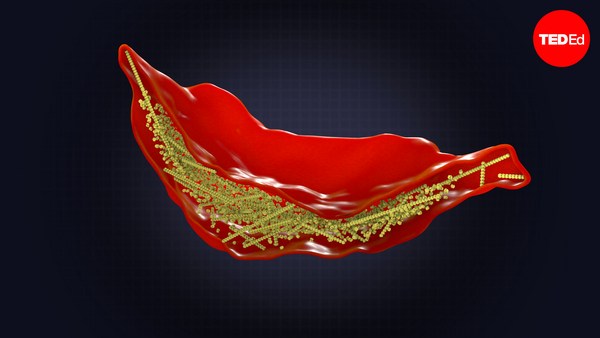

As they move around, leukocytes work like security personnel, constantly screening the blood, tissues, and organs for suspicious signs. This system mainly relies on cues called antigens. These molecular traces on the surface of pathogens and other foreign substances betray the presence of invaders. As soon as the leukocytes detect them, it takes only minutes for the body’s protective immune response to kick in.

Threats to our bodies are hugely variable, so the immune response has to be equally adaptable. That means relying on many different types of leukocytes to tackle threats in different ways.

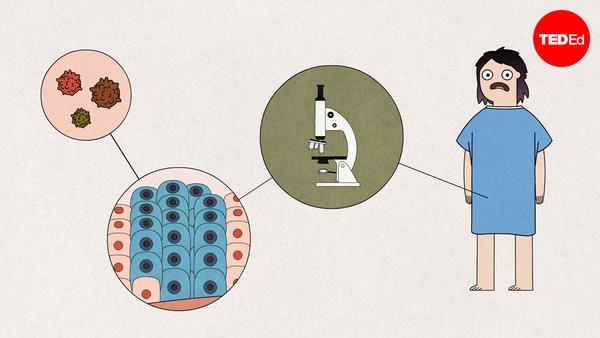

Despite this diversity, we classify leukocytes in two main cellular groups, which coordinate a two-pronged attack. First, phagocytes trigger the immune response by sending macrophages and dendritic cells into the blood. As these circulate, they destroy any foreign cells they encounter, simply by consuming them. That allows phagocytes to identify the antigen on the invaders they just ingested and transmit this information to the second major cell group orchestrating the defense, the lymphocytes.

A group of lymphocyte cells called T-cells go in search of infected body cells and swiftly kill them off. Meanwhile, B-cells and helper T-cells use the information gathered from the unique antigens to start producing special proteins called antibodies. This is the pièce de résistance: Each antigen has a unique, matching antibody that can latch onto it like a lock and key, and destroy the invading cells. B-cells can produce millions of these, which then cycle through the body and attack the invaders until the worst of the threat is neutralized.

While all of this is going on, familiar symptoms, like high temperatures and swelling, are actually processes designed to aid the immune response. A warmer body makes it harder for bacteria and viruses to reproduce and spread because they’re temperature-sensitive. And when body cells are damaged, they release chemicals that make fluid leak into the surrounding tissues, causing swelling. That also attracts phagocytes, which consume the invaders and the damaged cells.

Usually, an immune response will eradicate a threat within a few days. It won’t always stop you from getting ill, but that’s not its purpose. Its actual job is to stop a threat from escalating to dangerous levels inside your body. And through constant surveillance over time, the immune system provides another benefit: it helps us develop long-term immunity. When B- and T-cells identify antigens, they can use that information to recognize invaders in the future. So, when a threat revisits, the cells can swiftly deploy the right antibodies to tackle it before it affects any more cells. That’s how you can develop immunity to certain diseases, like chickenpox.

It doesn’t always work so well. Some people have autoimmune diseases, which trick the immune system into attacking the body’s own perfectly healthy cells. No one knows exactly what causes them, but these disorders sabotage the immune system to varying degrees, and underlie problems like arthritis, Type I diabetes, and multiple sclerosis.

For most individuals, however, a healthy immune system will successfully fight off an estimated 300 colds and innumerable other potential infections over the course of a lifetime. Without it, those threats would escalate into something far more dangerous. So the next time you catch a cold or scratch a mosquito bite, think of the immune system. We owe it our lives.