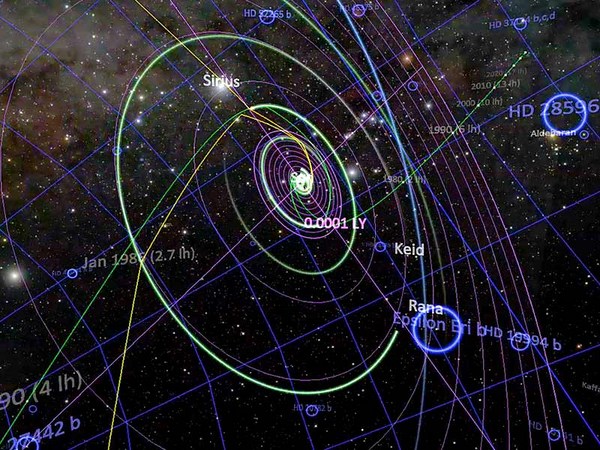

I'm the director of baster visualization at the American Museum of Natural History, a place that I grew up at and just a great honor to work at for almost 25 years now. That means we must have met each other right when you started. Yes. Let’s see. It’s almost 25 years. Twenty four years. It started in 1998, when the museum was actually rebuilding the Hayden Planetarium. And as our illustrious director, Neil deGrasse Tyson likes to say, it was the sort of goal was to kind of consider what the planetarium of the 21st century would be. And of course, the planetarium which was well-loved, the Hayden Planetarium as well of planetarium across the country. The first one in the US was the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, well-loved by everyone who goes there. But the technology was essentially a star projector in the middle of the room had a lot of personality. It looked like a giant ants, but projecting stars on the ceiling. And with the trends in virtual environments and data visualization research, the promise of that technology was again as a millennium project. That the rebuilding of the Hayden was to really look at what that technology could bring to our state of knowledge of the universe and create kind of a scale model of the universe, if you will kind of like a big train set. But accurate and authentic to actually explore space and to actually fly into the stars. I remember that the vision that the 2 of you outlined to me on my visit there because it was like, hey, we’re dreaming big. I mean, like, very big. And the idea was that the planetarium would be open in the afternoon for the general population. But in the morning it was going to be a global resource for astrophysicists to be able to sit in this big chair in the center. And I remember there was a big 3D ball. And our soft ball role was to track the animation paths that scientists and astrophysicists would be using so they could do the studies. And I remember, for any of this was built getting to have you take me to the tour of the Milky Way. Yeah. Our project that I came to the museum to join was called Digital Galaxy Project, right? So the museum has sort of chosen this as a central construct by which the shows productions would be made. And what that would entail is accounting for all the astronomical catalogs of the Milky Way galaxy that has distance information. And so the call to duty was to put together what became known as the Digital Universe 3D Atlas. And so the distances to stars, the distances to nebulae, the sort of objects that make up the galaxy This was presented when I interviewed and we had a meeting. I was as a little critical because all this talk about the galaxy, but I was sort of like, When you leave the galaxy, what are we going to see? Are we going to fold in the positions of galaxies beyond at first? And Neil deGrasse said, well, we had a lot to do just to chart the galaxy, but it was sort of like, you know, if you step outside the galaxy and don't see anything around it, that's sort of astronomy of the 1920s before Edwin Hubble distanced Andromeda, and we knew that we were in a much larger universe filled with other galaxies, other island universes as they were called. So we eventually got there. But while the technology was daunting, the video mapping to put together a high resolution display and all that. I think the concept is fairly simple that, you know, we look up into the night sky. We see the beautiful stars, Milky Way, go out in nature somewhere, go out in the mountains, and it’s glorious beyond belief. And but there's also that sobering knowledge that the constellations have had this constant sticks to the ancients saw the same way that we do. The stars were all in motion, but we live like fruit flies, where such a tiny timescale compared to the swirl of action that makes up the Milky Way. We have ways to measure all that action, which is astrophysics, but to put that all into a computer and be able to depict. I think it wasn’t exciting task. But it was a kind of a noble task. The mission to take Umm.. how’s that, how’s that. Go on then. that’s it was interesting. I felt that kind of parallel course looking back on it after we were building it to the Apollo 8th mission, where the first time that humans left the Earth and went to the Moon. It was all about the future, it was all about the Moon, Moon, Moon, Moon, and when we got there, the astronauts saw the Earth rise unexpectedly on Earth orbit. Around the Moon, 10 orbits around the Moon came back on Christmas Eve, 1968, a year that was tumultuous. World seemed to be falling apart, and it was the view of the Earth from the Moon. That was the important part, and I felt that here we were building an atlas of the Universe and we're going to go flying through it and, you know, Star Trek fashion through the stars. But the only way to sort of make sense of it all was to get out there and look back to not only our Earth, but our sun. Because when you move out into interstellar space, our dim little sun that we have the dimness to thank for its longevity, the five billion years that we've been evolving and we've still got a few billion years, you know, 5 billion years of fuel left before the Sun goes nova. But that The Sun and just even the the nearest sort of interstate stellar neighborhood is a very humbling view because the sun is fairly dim and it quickly gets lost against all the other stars and and then that neighborhood of stars becomes thing. We hope we highlight and make our recognizable. But then quickly, when you're moving out in the galaxies, you quickly lose the Milky Way and you realize a kind of sameness across the universe. The pale blue dot, the Carl Sagan pointed out, was this pixel, this bluish pixel caught in a sunbeam from Voyager as it left and was programmed to take sort of a family portrait. And NASA didn’t really want to do it. You know, it was sort of dedicated resources, and Carl felt that it was a very poetic thing to do is it took this family portrait of pictures at Mosaic. Look at the Solar System and his famous words of looking back and thinking about everything. All of history. The rivers of blood that have been spilled and so forth is all for slicing out a piece of a speck of this pale blue dot, all of life and its turmoil and its uniqueness, certainly to our world. But then you're confronting this vastness of the universe, and it's it's so vast. That, you know, you immediately start to think, you know, a galaxy you get lost in the field of This glow of just the myriad of galaxies, several million that have been charted in some digital sky or digital sky survey after survey. Every dot is a galaxy, every dot, several hundred billion stars. And at the rate, we're finding exoplanets easily a trillion worlds to every dot, every galaxy. And then you say, Well, is life unique? Most likely not. We are sort of, you know, chemistry that got together and started thinking and eating and and so forth. And there's the sign for the show. We are chemistry that got together and started thinking Carter as I listened to you and as I've read a lot of your material and have watched your work, These 2 words come to mind there is a just a position between you're as much a philosopher as you are an astrophysicist. So I wanted to be an astrophysicist, and I didn't go that direction. I felt a little challenged in the mirror. I come from a family of artists and I felt that in my educational path that since I wasn't going to pursue astrophysics, I felt a little lost. Visualization sort of brought me back to my own Starlee Thompson, who was heading up an Earth System modeling group early on in that concept of how to put together the Earth’s climate system between the atmosphere of the ocean and the vegetation. And all this At the National Center for Atmospheric Research brought me into visualization. and that led that was the path that led to back to New York, back to the Museum of Natural History. But. And the Museum of Natural History. You know, it’s inspired so many dioramas of Africa that were built when you only could get to Africa on a steamship, you know, and go on a safari. And these were remote places. And this absolute incredible artistry of these dioramas is that you stand there in the Serengeti Plain, you know, and but you're on the Upper West side of Manhattan, really? And that was the ghosts of those diorama proprietors and and back drop artist Perry Wilson, Rick Perry, Wilson, those incredible artists amongst many. But you come to work every day and you say Wow... That’s your comparison. That’s you’re going to live up to it. And so I think it was noble to try to create a system to look at the universe and think about our place in it. Neil Armstrong had an incredibly beautiful , insightful quote that he said, You know, in Apollo, you could cover the Moon up with your thumb. But then he said, it didn't make me feel big. It made me feel very, very small. Wow. So I think that that combination of thinking big and reminding ourselves how minute we are. And on a world where we depend on one another. And that view from space of no borders, the commonality, the air we breathe, our situation. And so that that’s the tension I think that we live on You invoked Armstrong. Tell us about what you're wearing. Well, for our 50th anniversary, I got 2 of these shirts. A good friend and co-worker, Micah A. Price, is my nephew’s best friend and he’s a crack programmer. He came and joined our team and so we are going to be presenting together. And he was going to be flying and talking. I saw these these sweatshirts on Facebook, and so I bought 2 of them. And so that was just a lot of fun. And to honor the man. Armstrong actually came into the planetarium and I got to fly. I got the honor of flying him around the universe. Wow. And I gave him the controls and and he was having a little trouble trying to see on the keyboard and stuff. And you know how to do this thing and everybody, you know, we had all the heavies from our museum and from the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. He apparently he flew the plane out, which was great with these guys came for this visit. But he he kind of took the hint and he sort of pushed away a little bit and he said, you know, in my day, I asked him, Neil, do simulators like this in Apollo? And he said, Well, in my day, we didn't even have PCs. So we laughed. He shook my hand and he said, thank you, Carter. That was a lot of fun. And you could have blown me over with a feather like. I’d love to. I have such fond memories of the museum, both sides, both the the terrestrial side will call the Museum of Natural History and the extraterrestrial side of that. Tell me about the kids and their reaction to space and give us some hope and optimism about our nation's youth. Well, you know, you work in a bubble and anything in your glutes, your project and all this stuff. And one day somebody threw a time out magazine on my desk and I had a paper clip and and before everything was so quiet anyway. So as early on it and they were asking kids. What’s the best thing to do in New York? Oh, now I have been a kid at the Hayden Planetarium. And that led to what I do, but there is a girl who’s about 12 or 13, and she said the best thing in New York is the space show at the museum natural history. We had cosmic collisions at the time, She said go see that show. She said I see that like 15 times and my dad’s taking me tomorrow for the 16th time and. That connects with the sea of children that you see that are coming in and who are wide eyed. And I think it touches them all, but it touches a few in a special way that may, you know, really make a big difference. But I think it touches them all. And the world is changing, so it's getting more complicated. Wars come and go. You know, I mean, it's hard to get over tribalism and so forth. But the climate is something that we caused, and you can't point a finger to any particular one. It's a common condition. But we’re going to need those great minds and the high school students I have I work for the gifted high school, Bergen County Academies in New Jersey. And these kids are smart. They have to test to get in there I see that brilliance in these young kids and their minds, and I just know they’re going to go forth in several places. They’ve gone on to work in the field that they were exposed to when they were interns of mine. And that's it's a tremendous honor. And it's a, you know, I don't have kids myself, but I feel like my students are Carter, I can imagine that there will be many kids who say my interest in space was because I met Dr. Carter Emmart when I was 12. I so appreciate the things that you're doing in the films that you're preparing for everybody to enjoy. Well, thank you. It’s an honor to be asked to TED stage. and it was an honor to just have this conversation with you today.