It's a great honor today to share with you The Digital Universe, which was created for humanity to really see where we are in the universe. And so I think we can roll the video that we have.

[The Himalayas.]

(Music)

The flat horizon that we've evolved with has been a metaphor for the infinite: unbounded resources and unlimited capacity for disposal of waste. It wasn't until we really left Earth, got above the atmosphere and had seen the horizon bend back on itself, that we could understand our planet as a limited condition. The Digital Universe Atlas has been built at the American Museum of Natural History over the past 12 years. We maintain that, put that together as a project to really chart the universe across all scales. What we see here are satellites around the Earth and the Earth in proper registration against the universe, as we see. NASA supported this work 12 years ago as part of the rebuilding of the Hayden Planetarium so that we would share this with the world.

The Digital Universe is the basis of our space show productions that we do -- our main space shows in the dome. But what you see here is the result of, actually, internships that we hosted with Linkoping University in Sweden. I've had 12 students work on this for their graduate work, and the result has been this software called Uniview and a company called SCISS in Sweden. This software allows interactive use, so this actual flight path and movie that we see here was actually flown live. I captured this live from my laptop in a cafe called Earth Matters on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where I live, and it was done as a collaborative project with the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art for an exhibit on comparative cosmology.

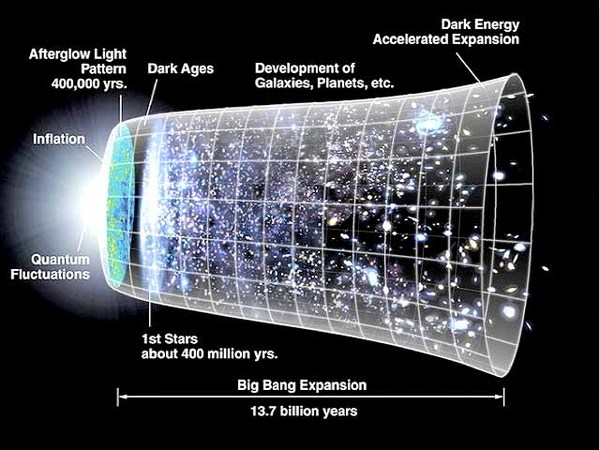

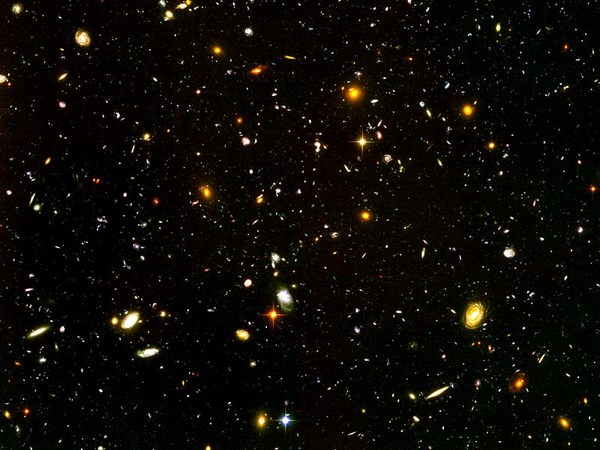

And so as we move out, we see continuously from our planet all the way out into the realm of galaxies, as we see here, light-travel time, giving you a sense of how far away we are. As we move out, the light from these distant galaxies have taken so long, we're essentially backing up into the past. We back so far up we're finally seeing a containment around us -- the afterglow of the Big Bang. This is the WMAP microwave background that we see. We'll fly outside it here, just to see this sort of containment. If we were outside this, it would almost be meaningless, in the sense as before time. But this our containment of the visible universe. We know the universe is bigger than that which we can see.

Coming back quickly, we see here the radio sphere that we jumped out of in the beginning, but these are positions, the latest positions of exoplanets that we've mapped, and our sun here, obviously, with our own solar system. What you're going to see -- we're going to have to jump in here pretty quickly between several orders of magnitude to get down to where we see the solar system -- these are the paths of Voyager 1, Voyager 2, Pioneer 11 and Pioneer 10, the first four spacecraft to have left the solar system. Coming in closer, picking up Earth, orbit of the Moon, and we see the Earth. This map can be updated, and we can add in new data.

I know Dr. Carolyn Porco is the camera P.I. for the Cassini mission. But here we see the complex trajectory of the Cassini mission color coded for different mission phases, ingeniously developed so that 45 encounters with the largest moon, Titan, which is larger that the planet Mercury, diverts the orbit into different parts of mission phase.

This software allows us to come close and look at parts of this. This software can also be networked between domes. We have a growing user base of this, and we network domes. And we can network between domes and classrooms. We're actually sharing tours of the universe with the first sub-Saharan planetarium in Ghana as well as new libraries that have been built in the ghettos in Columbia and a high school in Cambodia. And the Cambodians have actually controlled the Hayden Planetarium from their high school.

This is an image from Saturday, photographed by the Aqua satellite, but through the Uniview software. So you're seeing the edge of the Earth. This is Nepal. This is, in fact, right here is the valley of Lhasa, right here in Tibet. But we can see the haze from fires and so forth in the Ganges valley down below in India. This is Nepal and Tibet.

And just in closing, I'd just like to say this beautiful world that we live on -- here we see a bit of the snow that some of you may have had to brave in coming out -- so I'd like to just say that what the world needs now is a sense of being able to look at ourselves in this much larger condition now and a much larger sense of what home is. Because our home is the universe, and we are the universe, essentially. We carry that in us. And to be able to see our context in this larger sense at all scales helps us all, I think, in understanding where we are and who we are in the universe.

Thank you.

(Applause)