I want to talk to you today about a difficult topic that is close to me, and closer than you might realize to you.

I came to the UK 21 years ago, as an asylum-seeker. I was 21. I was forced to leave the Democratic Republic of the Congo, my home, where I was a student activist. I would love my children to be able to meet my family in the Congo.

But I want to tell you what the Congo has got to do with you. But first of all, I want you to do me a favor. Can you all please reach into your pockets and take out your mobile phone? Feel that familiar weight ... how naturally your finger slides towards the buttons.

(Laughter)

Can you imagine your world without it? It connects us to our loved ones, our family, friends and colleagues, at home and overseas. It is a symbol of an interconnected world.

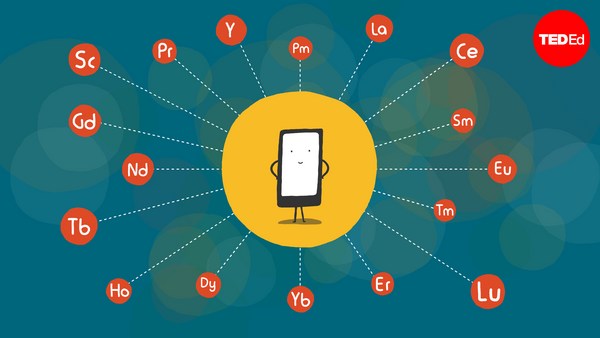

But what you hold in your hand leaves a bloody trail, and it all boils down to a mineral: tantalum, mined in the Congo as coltan. It is an anticorrosive heat conductor. It stores energy in our mobile phones, PlayStations and laptops. It is used in aerospace and medical equipment as an alloy. It is so powerful that we only need tiny amounts. It would be great if the story ended there.

Unfortunately, what you hold in your hand has not only enabled incredible technological development and industrial expansion, but it has also contributed to unimaginable human suffering.

Since 1996, over five million people have died in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Countless women, men and children have been raped, tortured or enslaved. Rape is used as a weapon of war, instilling fear and depopulating whole areas. The quest for extracting this mineral has not only aided, but it has fueled the ongoing war in the Congo.

But don't throw away your phones yet. Thirty thousand children are enlisted and are made to fight in armed groups. The Congo consistently scores dreadfully in global health and poverty rankings. But remarkably, the UN Environmental Programme has estimated the wealth of the country to be over 24 trillion dollars. The state-regulated mining industry has collapsed, and control over mines has splintered. Coltan is easily controlled by armed groups. One well-known illicit trade route is that across the border to Rwanda, where Congolese tantalum is disguised as Rwandan.

But don't throw away your phones yet, because the incredible irony is that the technology that has placed such unsustainable, devastating demands on the Congo is the same technology that has brought this situation to our attention. We only know so much about the situation in the Congo and in the mines because of the kind of communication the mobile phone allows. As with the Arab Spring, during the recent elections in the Congo, voters were able to send text messages of local polling stations to the headquarters in the capital, Kinshasa. And in the wake of the result, the diaspora has joined with the Carter Center, the Catholic Church and other observers, to draw attention to the undemocratic result.

The mobile phone has given people around the world an important tool towards gaining their political freedom. It has truly revolutionized the way we communicate on the planet. It has allowed momentous political change to take place. So, we are faced with a paradox. The mobile phone is an instrument of freedom and an instrument of oppression.

TED has always celebrated what technology can do for us, technology in its finished form. It is time to be asking questions about technology. Where does it come from? Who makes it? And for what? Here, I am speaking directly to you, the TED community, and to all those who might be watching on a screen, on your phone, across the world, in the Congo. All the technology is in place for us to communicate, and all the technology is in place to communicate this.

At the moment, there is no clear fair-trade solution. But there has been a huge amount of progress. The US has recently passed legislation to target bribery and misconduct in the Congo. Recent UK legislation could be used in the same way. In February, Nokia unveiled its new policy on sourcing minerals in the Congo, and there is a petition to Apple to make a conflict-free iPhone. There are campaigns spreading across university campuses to make their colleges conflict-free. But we're not there yet. We need to continue mounting pressure on phone companies to change their sourcing processes.

When I first came to the UK, 21 years ago, I was homesick. I missed my family and the friends I left behind. Communication was extremely difficult. Sending and receiving letters took months -- if you were lucky. Often, they never arrived. Even if I could have afforded the phone bills home, like most people in the Congo, my parents did not own a phone line.

Today, my two sons -- David and Daniel, can talk to my parents and get to know them. Why should we allow such a wonderful, brilliant and necessary product to be the cause of unnecessary suffering for human beings?

We demand fair-trade food and fair-trade clothes. It is time to demand fair-trade phones. This is an idea worth spreading.

Thank you.

(Applause)