I'm a huge believer in hands-on education. But you have to have the right tools. If I'm going to teach my daughter about electronics, I'm not going to give her a soldering iron. And similarly, she finds prototyping boards really frustrating for her little hands. So my wonderful student Sam and I decided to look at the most tangible thing we could think of: Play-Doh. And so we spent a summer looking at different Play-Doh recipes. And these recipes probably look really familiar to any of you who have made homemade play-dough -- pretty standard ingredients you probably have in your kitchen. We have two favorite recipes -- one that has these ingredients and a second that had sugar instead of salt. And they're great. We can make great little sculptures with these.

But the really cool thing about them is when we put them together. You see that really salty Play-Doh? Well, it conducts electricity. And this is nothing new. It turns out that regular Play-Doh that you buy at the store conducts electricity, and high school physics teachers have used that for years. But our homemade play-dough actually has half the resistance of commercial Play-Doh. And that sugar dough? Well it's 150 times more resistant to electric current than that salt dough. So what does that mean? Well it means if you them together you suddenly have circuits -- circuits that the most creative, tiny, little hands can build on their own.

(Applause)

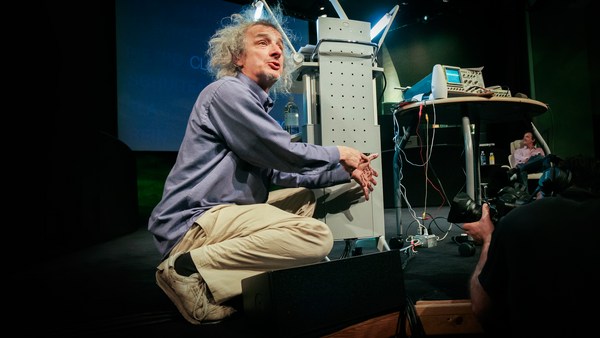

And so I want to do a little demo for you. So if I take this salt dough, again, it's like the play-dough you probably made as kids, and I plug it in -- it's a two-lead battery pack, simple battery pack, you can buy them at Radio Shack and pretty much anywhere else -- we can actually then light things up. But if any of you have studied electrical engineering, we can also create a short circuit. If I push these together, the light turns off. Right, the current wants to run through the play-dough, not through that LED. If I separate them again, I have some light. Well now if I take that sugar dough, the sugar dough doesn't want to conduct electricity. It's like a wall to the electricity. If I place that between, now all the dough is touching, but if I stick that light back in, I have light. In fact, I could even add some movement to my sculptures. If I want a spinning tail, let's grab a motor, put some play-dough on it, stick it on and we have spinning.

(Applause)

And once you have the basics, we can make a slightly more complicated circuit. We call this our sushi circuit. It's very popular with kids. I plug in again the power to it. And now I can start talking about parallel and series circuits. I can start plugging in lots of lights. And we can start talking about things like electrical load. What happens if I put in lots of lights and then add a motor? It'll dim. We can even add microprocessors and have this as an input and create squishy sound music that we've done. You could do parallel and series circuits for kids using this.

So this is all in your home kitchen. We've actually tried to turn it into an electrical engineering lab. We have a website, it's all there. These are the home recipes. We've got some videos. You can make them yourselves. And it's been really fun since we put them up to see where these have gone. We've had a mom in Utah who used them with her kids, to a science researcher in the U.K., and curriculum developers in Hawaii.

So I would encourage you all to grab some Play-Doh, grab some salt, grab some sugar and start playing. We don't usually think of our kitchen as an electrical engineering lab or little kids as circuit designers, but maybe we should.

Have fun. Thank you.

(Applause)