You might be wondering why I'm wearing sunglasses, and one answer to that is, because I'm here to talk about glamour. So, we all think we know what glamour is. Here it is. It's glamorous movie stars, like Marlene Dietrich. And it comes in a male form, too -- very glamorous. Not only can he shoot, drive, drink -- you know, he drinks wine, there actually is a little wine in there -- and of course, always wears a tuxedo. But I think that glamour actually has a much broader meaning -- one that is true for the movie stars and the fictional characters, but also comes in other forms.

A magazine? Well, it's certainly not this one. This is the least glamorous magazine on the newsstand -- it's all about sex tips. Sex tips are not glamorous. And Drew Barrymore, for all her wonderful charm, is not glamorous either. But there is a glamour of industry. This is Margaret Bourke-White's -- one of her pictures she did. Fantastic, glamorous pictures of steel mills and paper mills and all kinds of glamorous industrial places. And there's the mythic glamour of the garage entrepreneur. This is the Hewlett-Packard garage. We know everyone who starts a business in a garage ends up founding Hewlett-Packard. There's the glamour of physics. What could be more glamorous than understanding the entire universe, grand unification? And, by the way, it helps if you're Brian Greene -- he has other kinds of glamour.

And there is, of course, this glamour. This is very, very glamorous: the glamour of outer space -- and not the alien-style glamour, but the nice, clean, early '60s version. So what do we mean by glamour? Well, one thing you can do if you want to know what glamour means is you can look in the dictionary. And it actually helps a lot more if you look in a very old dictionary, in this case the 1913 dictionary. Because for centuries, glamour had a very particular meaning, and the word was actually used differently from the way we think of it. You had "a" glamour. It wasn't glamour as a quality -- you "cast a glamour." Glamour was a literal magic spell. Not a metaphorical one, the way we use it today, but a literal magic spell associated with witches and gypsies and to some extent, Celtic magic. And over the years, around the turn of the 20th century, it started to take on this other kind of deception -- this definition for any artificial interest in, or association with, an object through which it appears delusively magnified or glorified. But still, glamour is an illusion. Glamour is a magic spell. And there's something dangerous about glamour throughout most of history. When the witches cast a magic spell on you, it was not in your self-interest -- it was to get you to act against your interest.

Well of course, in the 20th century, glamour came to have this different meaning associated with Hollywood. And this is Hedy Lamarr. Hedy Lamarr said, "Anyone can look glamorous, all you have to do is sit there and look stupid." (Laughter) But in fact, with all due respect to Hedy -- about whom we'll hear more later -- there's a lot more to it. There was a tremendous amount of technical achievement associated with creating this Hollywood glamour. There were scores of retouchers and lighting experts and make-up experts. You can go to the museum of Hollywood history in Hollywood and see Max Factor's special rooms that he painted different colors depending on the complexion of the star he was going to make up. So you've got this highly stylized portrait of something that was not entirely of this earth -- it was a portrait of a star. And actually, we see glamorized photos of stars all the time -- they call them false color.

Glamour is a form of falsification, but falsification to achieve a particular purpose. It may be to illuminate the star; it may be to sell a film. And it involves a great deal of technique. It's not -- glamour is not something -- you don't wake up in the morning glamorous. I don't care who you are. Even Nicole Kidman doesn't wake up in the morning glamorous. There is a process of "idealization, glorification and dramatization," and it's not just the case for people. Glamour doesn't have to be people. Architectural photography -- Julius Schulman, who has talked about transfiguration, took this fabulous, famous picture of the Kauffman House. Architectural photography is extremely glamorous. It puts you into this special, special world. This is Alex Ross's comic book art, which appears to be extremely realistic, as part of his style is he gives you a kind of realism in his comic art. Except that light doesn't work this way in the real world.

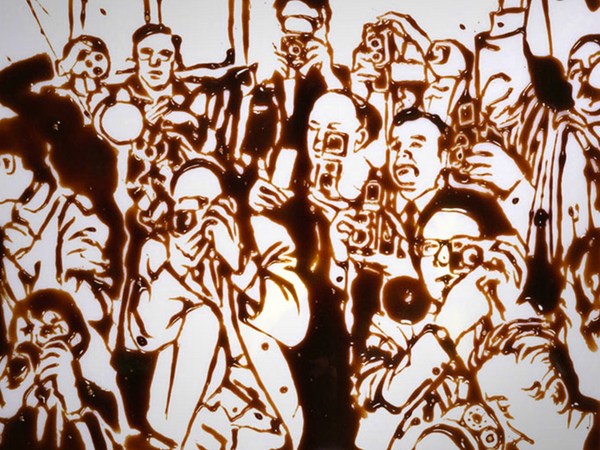

When you stack people in rows, the ones in the background look smaller than the ones in the foreground -- but not in the world of glamour. What glamour is all about -- I took this from a blurb in the table of contents of New York magazine, which was telling us that glamour is back -- glamour is all about transcending the everyday. And I think that that's starting to get at what the core that combines all sorts of glamour is. This is Filippino Lippi's 1543 portrait of Saint Apollonia. And I don't know who she is either, but this is the [16th] century equivalent of a supermodel. It's a very glamorous portrait. Why is it glamorous? It's glamorous, first, because she is beautiful -- but that does not make you glamorous, that only makes you beautiful. She is graceful, she is mysterious and she is transcendent, and those are the central qualities of glamour. You don't see her eyes; they're looking downward. She's not looking away from you exactly, but you have to mentally imagine her world. She's encouraging you to contemplate this higher world to which she belongs, where she can be completely tranquil while holding the iron instruments of her death by torture. Mel Gibson's "Passion Of The Christ" -- not glamorous. That's glamour: that's Michelangelo's "Pieta," where Mary is the same age as Jesus and they're both awfully happy and pleasant.

Glamour invites us to live in a different world. It has to simultaneously be mysterious, a little bit distant -- that's why, often in these glamour shots, the person is not looking at the audience, it's why sunglasses are glamorous -- but also not so far above us that we can't identify with the person. In some sense, there has to be something like us. So as I say, in religious art, you know, God is not glamorous. God cannot be glamorous because God is omnipotent, omniscient -- too far above us. And yet you will see in religious art, saints or the Virgin Mary will often be portrayed -- not always -- in glamorous forms. As I said earlier, glamour does not have to be about people, but it has to have this transcendent quality. What is it about Superman? Aside from Alex Ross's style, which is very glamorous, one thing about Superman is he makes you believe that a man can fly.

Glamour is all about transcending this world and getting to an idealized, perfect place. And this is one reason that modes of transportation tend to be extremely glamorous. The less experience we have with them, the more glamorous they are. So you can do a glamorized picture of a car, but you can't do a glamorized picture of traffic. You can do a glamorized picture of an airplane, but not the inside. The notion is that it's going to transport you, and the story is not about, you know, the guy in front of you in the airplane, who has this nasty little kid, or the big cough. The story is about where you're arriving, or thinking about where you're arriving. And this sense of being transported is one reason that we have glamour styling. This sort of streamlining styling is not just glamorous because we associate it with movies of that period, but because, in it's streamlining, it transports us from the everyday.

The same thing -- arches are very glamorous. Arches with stained glass -- even more glamorous. Staircases that curve away from you are glamorous. I happen to find that particular staircase picture very glamorous because, to me, it captures the whole promise of the academic contemplative life -- but maybe that's because I went to Princeton. Anyway, skylines are super glamorous, city streets -- not so glamorous. You know, when you get, actually to this town it has reality. The horizon, the open road, is very, very glamorous. There are few things more glamorous than the horizon -- except, possibly, multiple horizons. Of course, here you don't feel the cold, or the heat -- you just see the possibilities. In order to pull glamour off, you need this Renaissance quality of sprezzatura, which is a term coined by Castiglione in his book, "The Book Of The Courtier." There's the not-glamorous version of what it looks like today, after a few centuries.

And sprezzatura is the art that conceals art. It makes things look effortless. You don't think about how Nicole Kidman is maneuvering that dress -- she just looks completely natural. And I remember reading, after the Lara Croft movies, how Angelina Jolie would go home completely black and blue. Of course, they covered that with make-up, because Lara Croft did all those same stunts -- but she doesn't get black and blue, because she has sprezzatura. "To conceal all art and make whatever is done or said appear to be without effort": And this is one of the critical aspects of glamour. Glamour is about editing. How do you create the sense of transcendence, the sense of evoking a perfect world? The sense of, you know, life could be better, I could join this -- I could be a perfect person, I could join this perfect world. We don't tell you all the grubby details.

Now, this was kindly lent to me by Jeff Bezos, from last year. This is underneath Jeff's desk. This is what the real world of computers, lamps, electrical appliances of all kinds, looks like. But if you look in a catalog -- particularly a catalog of modern, beautiful objects for your home -- it looks like this. There are no cords. Look next time you get these catalogs in your mail -- you can usually figure out where they hid the cord. But there's always this illusion that if you buy this lamp, you will live in a world without cords. (Laughter) And the same thing is true of, if you buy this laptop or you buy this computer -- and even in these wireless eras, you don't get to live in the world without cords. You have to have mystery and you have to have grace. And there she is -- Grace. This is the most glamorous picture, I think, ever. Part of the thing is that, in "Rear Window," the question is, is she too glamorous to live in his world? And the answer is no, but of course it's really just a movie.

Here's Hedy Lamarr again. And, you know, this kind of head covering is extremely glamorous because, like sunglasses, it conceals and reveals at the same time. Translucence is glamorous -- that's why all these people wear pearls. It's why barware is glamorous. Glamour is translucent -- not transparent, not opaque. It invites us into the world but it doesn't give us a completely clear picture. And I think if Grace Kelly is the most glamorous person, maybe a spiral staircase with glass block may be the most glamorous interior shot, because a spiral staircase is incredibly glamorous. It has that sense of going up and away, and yet you never think about how you would really trip if you were -- particularly going down. And of course glass block has that sense of translucence. So, this session's supposed to be about pure pleasure but glamour's really partly about meaning. All individuals and all cultures have ideals that cannot possibly be realized in reality.

They have contradictions, they uphold principles that are incommensurable with each other -- whatever it is -- and yet these ideals give meaning and purpose to our lives as cultures and as individuals. And the way we deal with that is we displace them -- we put them into a golden world, an imagined world, an age of heroes, the world to come. And in the life of an individual, we often associate that with some object. The white picket fence, the perfect house. The perfect kitchen -- no bills on the counter in the perfect kitchen. You know, you buy that Viking range, this is what your kitchen will look like. The perfect love life -- symbolized by the perfect necklace, the perfect diamond ring. The perfect getaway in your perfect car. This is an interior design firm that is literally called Utopia. The perfect office -- again, no cords, as far as I can tell. And certainly, no, it doesn't look a thing like my office. I mean, there's no paper on the desk. We want this golden world. And some people get rich enough, and if they have their ideals -- in a sort of domestic sense, they get to acquire their perfect world.

Dean Koontz built this fabulous home theater, which is -- I don't think accidentally -- in Art Deco style. That symbolizes this sense of being safe and at home. This is not always good, because what is your perfect world? What is your ideal, and also, what has been edited out? Is it something important? "The Matrix" is a movie that is all about glamour. I could do a whole talk on "The Matrix" and glamour. It was criticized for glamorizing violence, because, look -- sunglasses and those long coats, and, of course, they could walk up walls and do all these kinds of things that are impossible in the real world. This is another Margaret Bourke-White photo. This is from Soviet Union. Attractive. I mean, look how happy the people are, and good-looking too. You know, we're marching toward Utopia.

I'm not a fan of PETA, but I think this is a great ad. Because what they're doing is they're saying, your coat's not so glamorous, what's been edited out is something important. But actually, what's even more important than remembering what's been edited out is thinking, are the ideals good? Because glamour can be very totalitarian and deceptive. And it's not just a matter of glamorizing cleaning your floor. This is from "Triumph Of The Will" -- brilliant editing to cut together things. There's a glamour shot. National Socialism is all about glamour. It was a very aesthetic ideology. It was all about cleaning up Germany, and the West, and the world, and ridding it of anything unglamorous. So glamour can be dangerous.

I think glamour has a genuine appeal, has a genuine value. I'm not against glamour. But there's a kind of wonder in the stuff that gets edited away in the cords of life. And there is both a way to avoid the dangers of glamour and a way to broaden your appreciation of it. And that's to take Isaac Mizrahi's advice and confront the manipulation of it all, and sort of admit that manipulation is something that we enjoy, but also enjoy how it happens. And here's Hedy Lamarr. She's very glamorous but, you know, she invented spread-spectrum technology. So she's even more glamorous if you know that she really wasn't stupid, even though she thought she could look stupid.

David Hockney talks about how the appreciation of this very glamorous painting is heightened if you think about the fact that it takes two weeks to paint this splash, which only took a fraction of a second to happen. There is a book out in the bookstore -- it's called "Symphony In Steel," and it's about the stuff that's hidden under the skin of the Disney Center. And that has a fascination. It's not necessarily glamorous, but unveiling the glamour has an appeal. There's a wonderful book called "Crowns" that's all these glamour pictures of black women in their church hats. And there's a quote from one of these women, and she talks about, "As a little girl, I'd admire women at church with beautiful hats. They looked like beautiful dolls, like they'd just stepped out of a magazine. But I also knew how hard they worked all week. Sometimes under those hats there's a lot of joy and a lot of sorrow." And, actually, you get more appreciation for glamour when you realize what went into creating it. Thank you.