"Judge, I want to tell you something. I want to tell you something. I been watching you and you're not two-faced. You treat everybody the same."

That was said to me by a transgender prostitute who before I had gotten on the bench had fired her public defender, insulted the court officer and yelled at the person sitting next to her, "I don't know what you're looking at. I look better than the girl you're with."

(Laughter)

She said this to me after I said her male name low enough so that it could be picked up by the record, but I said her female name loud enough so that she could walk down the aisle towards counselor's table with dignity. This is procedural justice, also known as procedural fairness, at its best.

You see, I am the daughter of an African-American garbageman who was born in Harlem and spent his summers in the segregated South.

Soy la hija de una peluquera dominicana.

I do that to make sure you're still paying attention.

(Laughter)

I'm the daughter of a Dominican beautician who came to this country for a better life for her unborn children. My parents taught me, you treat everyone you meet with dignity and respect, no matter how they look, no matter how they dress, no matter how they spoke. You see, the principles of fairness were taught to me at an early age, and unbeknownst to me, it would be the most important lesson that I carried with me to the Newark Municipal Court bench. And because I was dragged off the playground at the early age of 10 to translate for family members as they began to migrate to the United States, I understand how daunting it can be for a person, a novice, to navigate any government system.

Every day across America and around the globe, people encounter our courts, and it is a place that is foreign, intimidating and often hostile towards them. They are confused about the nature of their charges, annoyed about their encounters with the police and facing consequences that might impact their relationships, their finances and even their liberty.

Let me paint a picture for you of what it's like for the average person who encounters our courts. First, they're annoyed as they're probed going through court security. They finally get through court security, they walk around the building, they ask different people the same question and get different answers. When they finally get to where they're supposed to be, it gets really bad when they encounter the courts.

What would you think if I told you that you could improve people's court experience, increase their compliance with the law and court orders, all the while increasing the public's trust in the justice system with a simple idea? Well, that simple idea is procedural justice and it's a concept that says that if people perceive they are treated fairly and with dignity and respect, they'll obey the law. Well, that's what Yale professor Tom Tyler found when he began to study as far back in the '70s why people obey the law. He found that if people see the justice system as a legitimate authority to impose rules and regulations, they would follow them. His research concluded that people would be satisfied with the judge's rulings, even when the judge ruled against them, if they perceived that they were treated fairly and with dignity and respect. And that perception of fairness begins with what? Begins with how judges speak to court participants.

Now, being a judge is sometimes like having a reserve seat to a tragic reality show that has no commercial interruptions and no season finale. It's true. People come before me handcuffed, drug-sick, depressed, hungry and mentally ill. When I saw that their need for help was greater than my fear of appearing vulnerable on the bench, I realized that not only did I need to do something, but that in fact I could do something.

The good news is is that the principles of procedural justice are easy and can be implemented as quickly as tomorrow. The even better news, that it can be done for free.

(Laughter)

The first principle is voice. Give people an opportunity to speak, even when you're not going to let them speak. Explain it. "Sir, I'm not letting you speak right now. You don't have an attorney. I don't want you to say anything that's going to hurt your case." For me, assigning essays to defendants has been a tremendous way of giving them voice.

I recently gave an 18-year-old college student an essay. He lamented his underage drinking charge. As he stood before me reading his essay, his voice cracking and his hands trembling, he said that he worried that he had become an alcoholic like his mom, who had died a couple of months prior due to alcohol-related liver disease.

You see, assigning a letter to my father, a letter to my son, "If I knew then what I know now ..." "If I believed one positive thing about myself, how would my life be different?" gives the person an opportunity to be introspective, go on the inside, which is where all the answers are anyway. But it also gives them an opportunity to share something with the court that goes beyond their criminal record and their charges.

The next principle is neutrality. When increasing public trust in the justice system, neutrality is paramount. The judge cannot be perceived to be favoring one side over the other. The judge has to make a conscious decision not to say things like, "my officer," "my prosecutor," "my defense attorney." And this is challenging when we work in environments where you have people assigned to your courts, the same people coming in and out of your courts as well. When I think of neutrality, I'm reminded of when I was a new Rutgers Law grad and freshly minted attorney, and I entered an arbitration and I was greeted by two grey-haired men who were joking about the last game of golf they played together and planning future social outings. I knew my client couldn't get a fair shot in that forum.

The next principle is understand. It is critical that court participants understand the process, the consequences of the process and what's expected of them. I like to say that legalese is the language we use to confuse.

(Laughter)

I am keenly aware that the people who appear before me, many of them have very little education and English is often their second language.

So I speak plain English in court. A great example of this was when I was a young judge -- oh no, I mean younger judge.

(Laughter)

When I was a younger judge, a senior judge comes to me, gives me a script and says, "If you think somebody has mental health issues, ask them these questions and you can get your evaluation." So the first time I saw someone who had what I thought was a mental health issue, I went for my script and I started to ask questions.

"Um, sir, do you take psycho -- um, psychotrop -- psychotropic medication?"

"Nope."

"Uh, sir, have you treated with a psychiatrist before?"

"Nope."

But it was obvious that the person was suffering from mental illness. One day, in my frustration, I decided to scrap the script and ask one question.

"Ma'am, do you take medication to clear your mind?"

"Yeah, judge, I take Haldol for my schizophrenia, Xanax for my anxiety."

The question works even when it doesn't.

"Mr. L, do you take medication to clear your mind?"

"No, judge, I don't take no medication to clear my mind. I take medication to stop the voices in my head, but my mind is fine."

(Laughter)

You see, once people understand the question, they can give you valuable information that allows the court to make meaningful decisions about the cases that are before them.

The last principle is respect, that without it none of the other principles can work. Now, respect can be as simple as, "Good afternoon, sir." "Good morning, ma'am." It's looking the person in the eye who is standing before you, especially when you're sentencing them. It's when I say, "Um, how are you doing today? And what's going on with you?" And not as a greeting, but as someone who is actually interested in the response. Respect is the difference between saying, "Ma'am, are you having difficulty understanding the information in the paperwork?" versus, "You can read and write, can't you?" when you've realized there's a literacy issue. And the good thing about respect is that it's contagious. People see you being respectful to other folks and they impute that respect to themselves. You see, that's what the transgender prostitute was telling me. I'm judging you just as much as you think you may be judging me.

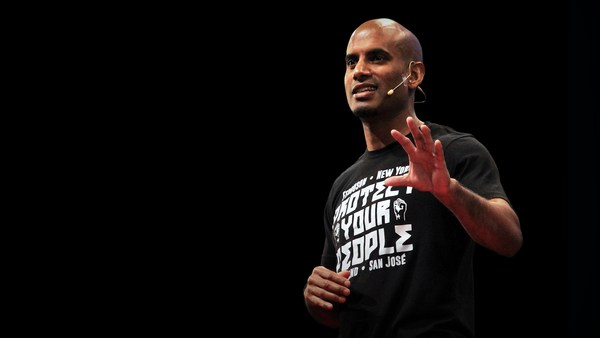

Now, I am not telling you what I think, I am telling you what I have lived, using procedural justice to change the culture at my courthouse and in the courtroom. After sitting comfortably for seven months as a traffic court judge, I was advised that I was being moved to the criminal court, Part Two, criminal courtroom. Now, I need you to understand, this was not good news.

(Laughter)

It was not. Part Two was known as the worst courtroom in the city, some folks would even say in the state. It was your typical urban courtroom with revolving door justice, you know, your regular lineup of low-level offenders -- you know, the low-hanging fruit, the drug-addicted prostitute, the mentally ill homeless person with quality-of-life tickets, the high school dropout petty drug dealer and the misguided young people -- you know, those folks doing a life sentence 30 days at a time.

Fortunately, the City of Newark decided that Newarkers deserved better, and they partnered with the Center for Court Innovation and the New Jersey Judiciary to create Newark Community Solutions, a community court program that provided alternative sanctions. This means now a judge can sentence a defendant to punishment with assistance. So a defendant who would otherwise get a jail sentence would now be able to get individual counseling sessions, group counseling sessions as well as community giveback, which is what we call community service.

The only problem is that this wonderful program was now coming to Newark and was going to be housed where? Part Two criminal courtroom. And the attitudes there were terrible. And the reason that the attitudes were terrible there was because everyone who was sent there understood they were being sent there as punishment. The officers who were facing disciplinary actions at times, the public defender and prosecutor felt like they were doing a 30-day jail sentence on their rotation, the judges understood they were being hazed just like a college sorority or fraternity. I was once told that an attorney who worked there referred to the defendants as "the scum of the earth" and then had to represent them. I would hear things from folks like, "Oh, how could you work with those people? They're so nasty. You're a judge, not a social worker."

But the reality is that as a society, we criminalize social ills, then sent people to a judge and say, "Do something." I decided that I was going to lead by example. So my first foray into the approach came when a 60-something-year-old man appeared before me handcuffed. His head was lowered and his body was showing the signs of drug withdrawal. I asked him how long he had been addicted, and he said, "30 years." And I asked him, "Do you have any kids?" And he said, "Yeah, I have a 32-year-old son." And I said, "Oh, so you've never had the opportunity to be a father to your son because of your addiction." He began to cry. I said, "You know what, I'm going to let you go home, and you'll come back in two weeks, and when you come back, we'll give you some assistance for your addiction." Surprisingly, two weeks passed and he was sitting the courtroom. When he came up, he said, "Judge, I came back to court because you showed me more love than I had for myself." And I thought, my God, he heard love from the bench? I could do this all day.

(Laughter)

Because the reality is that when the court behaves differently, then naturally people respond differently. The court becomes a place you can go to for assistance, like the 60-something-year-old schizophrenic homeless woman who was in distress and fighting with the voices in her head, and barges into court, and screams, "Judge! I just came by to see how you were doing." I had been monitoring her case for a couple of months, her compliance with her medication, and had just closed out her case a couple of weeks ago. On this day she needed help, and she came to court. And after four hours of coaxing by the judge, the police officers and the staff, she is convinced to get into the ambulance that will take her to crisis unit so that she can get her medication.

People become connected to their community when the court changes, like the 50-something-year-old man who told me, "Community service was terrible, Judge. I had to clean the park, and it was full of empty heroin envelopes, and the kids had to play there." As he wrung his hands, he confessed, "Judge, I realized that it was my fault, because I used that same park to get high, and before you sent me there to do community service, I had never gone to the park when I wasn't high, so I never noticed the children playing there." Every addict in the courtroom lowered their head. Who better to teach that lesson?

It helps the court reset its relationship with the community, like with the 20-something-year-old guy who gets a job interview through the court program. He gets a job interview at an office cleaning company, and he comes back to court to proudly say, "Judge, I even worked in my suit after the interview, because I wanted the guy to see how bad I wanted the job."

It's what happens when a person in authority treats you with dignity and respect, like the 40-something-year-old guy who struts down the aisle and says, "Judge, do you notice anything different?" And when I look up, he's pointing at his new teeth that he was able to get after getting a referral from the program, but he was able to get them to replace the old teeth that he lost as a result of years of heroin addiction. When he looks in the mirror, now he sees somebody who is worth saving.

You see, I have a dream and that dream is that judges will use these tools to revolutionize the communities that they serve. Now, these tools are not miracle cure-alls, but they get us light-years closer to where we want to be, and where we want to be is a place that people enter our halls of justice and believe they will be treated with dignity and respect and know that justice will be served there. Imagine that, a simple idea.

Thank you.

(Applause)