"Pheromone" is a very powerful word. It conjures up sex, abandon, loss of control, and you can see, it's very important as a word. But it's only 50 years old. It was invented in 1959. Now, if you put that word into the web, as you may have done, you'll come up with millions of hits, and almost all of those sites are trying to sell you something to make you irresistible for 10 dollars or more. Now, this is a very attractive idea, and the molecules they mention sound really science-y. They've got lots of syllables. It's things like androstenol, androstenone or androstadienone. It gets better and better, and when you combine that with white lab coats, you must imagine that there is fantastic science behind this. But sadly, these are fraudulent claims supported by dodgy science.

The problem is that, although there are many good scientists working on what they think are human pheromones, and they're publishing in respectable journals, at the basis of this, despite very sophisticated experiments, there really is no good science behind it, because it's based on a problem, which is nobody has systematically gone through all the odors that humans produce -- and there are thousands of molecules that we give off. We're mammals. We produce a lot of smell. Nobody has gone through systematically to work out which molecules really are pheromones. They've just plucked a few, and all these experiments are based on those, but there's no good evidence at all.

Now, that's not to say that smell is not important to people. It is, and some people are real enthusiasts, and one of these was Napoleon. And famously, you may remember that out on the campaign trail for war, he wrote to his lover, Empress Josephine, saying, "Don't wash. I'm coming home." (Laughter) So he didn't want to lose any of her richness in the days before he'd get home, and it is still, you'll find websites that offer this as a major quirk. At the same time, though, we spend about as much money taking the smells off us as putting them back on in perfumes, and perfumes are a multi-billion-dollar business.

So what I want to do in the rest of this talk is tell you about what pheromones really are, tell you why I think we would expect humans to have pheromones, tell you about some of the confusions in pheromones, and then finally, I want to end with a promising avenue which shows us the way we ought to be going.

So the ancient Greeks knew that dogs sent invisible signals between each other. A female dog in heat sent an invisible signal to male dogs for miles around, and it wasn't a sound, it was a smell. You could take the smell from the female dog, and the dogs would chase the cloth. But the problem for everybody who could see this effect was that you couldn't identify the molecules. You couldn't demonstrate it was chemical. The reason for that, of course, is that each of these animals produces tiny quantities, and in the case of the dog, males dogs can smell it, but we can't smell it. And it was only in 1959 that a German team, after spending 20 years in search of these molecules, discovered, identified, the first pheromone, and this was the sex pheromone of a silk moth. Now, this was an inspired choice by Adolf Butenandt and his team, because he needed half a million moths to get enough material to do the chemical analysis. But he created the model for how you should go about pheromone analysis. He basically went through systematically, showing that only the molecule in question was the one that stimulated the males, not all the others. He analyzed it very carefully. He synthesized the molecule, and then tried the synthesized molecule on the males and got them to respond and showed it was, indeed, that molecule. That's closing the circle. That's the thing which has never been done with humans: nothing systematic, no real demonstration.

With that new concept, we needed a new word, and that was the word "pheromone," and it's basically transferred excitement, transferred between individuals, and since 1959, pheromones have been found right the way across the animal kingdom, in male animals, in female animals. It works just as well underwater for goldfish and lobsters. And almost every mammal you can think of has had a pheromone identified, and of course, an enormous number of insects.

So we know that pheromones exist right the way across the animal kingdom. What about humans? Well, the first thing, of course, is that we're mammals, and mammals are smelly. As any dog owner can tell you, we smell, they smell.

But the real reason we might think that humans have pheromones is the change that occurs as we grow up. The smell of a room of teenagers is quite different from the smell of a room of small children. What's changed? And of course, it's puberty. Along with the pubic hair and the hair in the armpits, new glands start to secrete in those places, and that's what's making the change in smell. If we were any other kind of mammal, or any other kind of animal, we would say, "That must be something to do with pheromones," and we'd start looking properly.

But there are some problems, and this is why, I think, people have not looked for pheromones so effectively in humans. There are, indeed, problems. And the first of these is perhaps surprising. It's all about culture. Now moths don't learn a lot about what is good to smell, but humans do, and up to the age of about four, any smell, no matter how rancid, is simply interesting. And I understand that the major role of parents is to stop kids putting their fingers in poo, because it's always something nice to smell. But gradually we learn what's not good, and one of the things we learn at the same time as what is not good is what is good.

Now, the cheese behind me is a British, if not an English, delicacy. It's ripe blue Stilton. Liking it is incomprehensible to people from other countries. Every culture has its own special food and national delicacy. If you were to come from Iceland, your national dish is deep rotted shark. Now, all of these things are acquired tastes, but they form almost a badge of identity. You're part of the in-group.

The second thing is the sense of smell. Each of us has a unique odor world, in the sense that what we smell, we each smell a completely different world. Now, smell was the hardest of the senses to crack, and the Nobel Prize awarded to Richard Axel and Linda Buck was only awarded in 2004 for their discovery of how smell works. It's really hard, but in essence, nerves from the brain go up into the nose and on these nerves exposed in the nose to the outside air are receptors, and odor molecules coming in on a sniff interact with these receptors, and if they bond, they send the nerve a signal which goes back into the brain. We don't just have one kind of receptor. If you're a human, you have about 400 different kinds of receptors, and the brain knows what you're smelling because of the combination of receptors and nerve cells that they trigger, sending messages up to the brain in a combinatorial fashion. But it's a bit more complicated, because each of those 400 comes in various variants, and depending which variant you have, you might smell coriander, or cilantro, that herb, either as something delicious and savory or something like soap. So we each have an individual world of smell, and that complicates anything when we're studying smell.

Well, we really ought to talk about armpits, and I have to say that I do have particularly good ones. Now, I'm not going to share them with you, but this is the place that most people have looked for pheromones. There is one good reason, which is, the great apes have armpits as their unique characteristic. The other primates have scent glands in other parts of the body. The great apes have these armpits full of secretory glands producing smells all the time, enormous numbers of molecules. When they're secreted from the glands, the molecules are odorless. They have no smell at all, and it's only the wonderful bacteria growing on the rainforest of hair that actually produces the smells that we know and love. And so incidentally, if you want to reduce the amount of smell, clear-cutting your armpits is a very effective way of reducing the habitat for bacteria, and you'll find they remain less smelly for much longer. But although we've focused on armpits, I think it's partly because they're the least embarrassing place to go and ask people for samples. There is actually another reason why we might not be looking for a universal sex pheromone there, and that's because 20 percent of the world's population doesn't have smelly armpits like me. And these are people from China, Japan, Korea, and other parts of northeast Asia. They simply don't secrete those odorless precursors that the bacteria love to use to produce the smells that in an ethnocentric way we always thought of as characteristic of armpits. So it doesn't apply to 20 percent of the world.

So what should we be doing in our search for human pheromones? I'm fairly convinced that we do have them. We're mammals, like everybody else who's a mammal, and we probably do have them. But what I think we should do is go right back to the beginning, and basically look all over the body. No matter how embarrassing, we need to search and go for the first time where no one else has dared tread. It's going to be difficult, it's going to be embarrassing, but we need to look. We also need to go back to the ideas that Butenandt used when he was studying the silk moth. We need to go back and look systematically at all the molecules that are being produced, and work out which ones are really involved. It isn't good enough simply to pluck a couple and say, "They'll do." We have to actually demonstrate that they really have the effects we claim.

There is one team that I'm actually very impressed by. They're in France, and their previous success was identifying the rabbit mammary pheromone. They've turned their attention now to human babies and mothers.

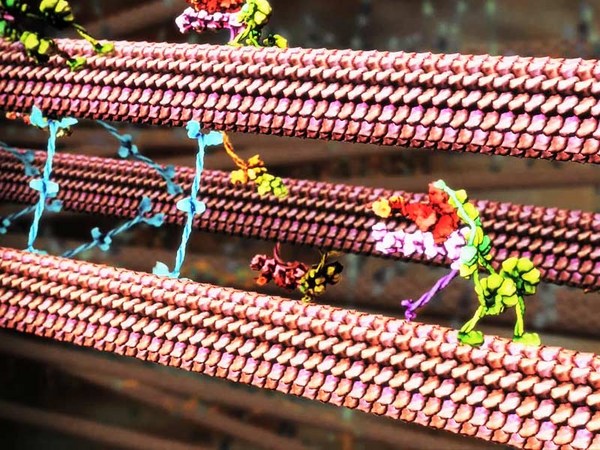

So this is a baby having a drink of milk from its mother's breast. Her nipple is completely hidden by the baby's head, but what you'll notice is a white droplet with an arrow pointing to it, and that's the secretion from the areolar glands. Now, we all have them, men and women, and these are the little bumps around the nipple, and if you're a lactating woman, these start to secrete. It's a very interesting secretion. What Benoist Schaal and his team developed was a simple test to investigate what the effect of this secretion might be, in effect, a simple bioassay. So this is a sleeping baby, and under its nose, we've put a clean glass rod. The baby remains sleeping, showing no interest at all. But if we go to any mother who is secreting from the areolar glands, so it's not about recognition, it can be from any mother, if we take the secretion and now put it under the baby's nose, we get a very different reaction. It's a connoisseur's reaction of delight, and it opens its mouth and sticks out its tongue and starts to suck. Now, since this is from any mother, it could really be a pheromone. It's not about individual recognition. Any mother will do.

Now, why is this important, apart from being simply very interesting? It's because women vary in the number of areolar glands that they have, and there is a correlation between the ease with which babies start to suckle and the number of areolar glands she has. It appears that the more secretions she's got, the more likely the baby is to suckle quickly. If you're a mammal, the most dangerous time in life is the first few hours after birth. You have to get that first drink of milk, and if you don't get it, you won't survive. You'll be dead. Since many babies actually find it difficult to take that first meal, because they're not getting the right stimulus, if we could identify what that molecule was, and the French team are being very cautious, but if we could identify the molecule, synthesize it, it would then mean premature babies would be more likely to suckle, and every baby would have a better chance of survival. So what I want to argue is this is one example of where a systematic, really scientific approach can actually bring you a real understanding of pheromones. There could be all sorts of medical interventions. There could be all sorts of things that humans are doing with pheromones that we simply don't know at the moment. What we need to remember is pheromones are not just about sex. They're about all sorts of things to do with a mammal's life. So do go forward and do search for more. There's lots to find.

Thank you very much.

(Applause)