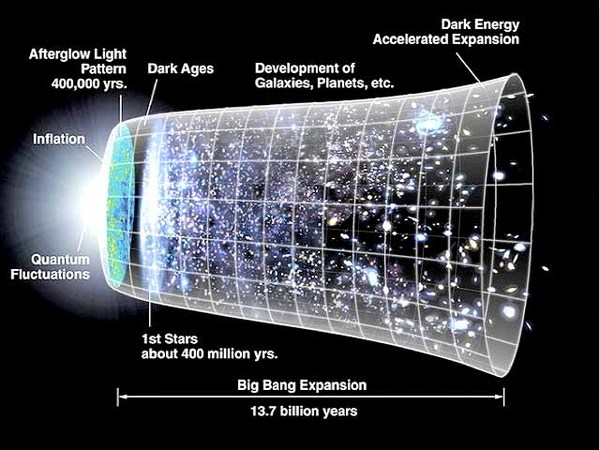

As technology progresses, and as it advances, many of us assume that these advances make us more intelligent, make us smarter and more connected to the world. And what I'd like to argue is that that's not necessarily the case, as progress is simply a word for change, and with change you gain something, but you also lose something.

And to really illustrate this point, what I'd like to do is to show you how technology has dealt with a very simple, a very common, an everyday question. And that question is this. What time is it? What time is it? If you glance at your iPhone, it's so simple to tell the time. But, I'd like to ask you, how would you tell the time if you didn't have an iPhone? How would you tell the time, say, 600 years ago? How would you do it?

Well, the way you would do it is by using a device that's called an astrolabe. So, an astrolabe is relatively unknown in today's world. But, at the time, in the 13th century, it was the gadget of the day. It was the world's first popular computer. And it was a device that, in fact, is a model of the sky. So, the different parts of the astrolabe, in this particular type, the rete corresponds to the positions of the stars. The plate corresponds to a coordinate system. And the mater has some scales and puts it all together.

If you were an educated child, you would know how to not only use the astrolabe, you would also know how to make an astrolabe. And we know this because the first treatise on the astrolabe, the first technical manual in the English language, was written by Geoffrey Chaucer. Yes, that Geoffrey Chaucer, in 1391, to his little Lewis, his 11-year-old son. And in this book, little Lewis would know the big idea.

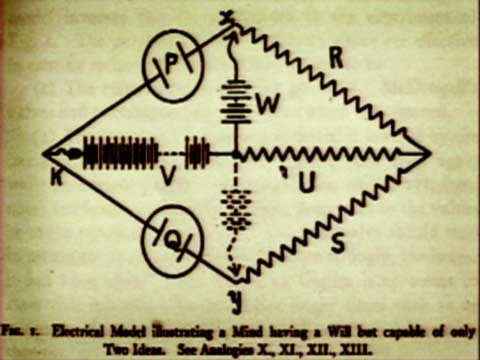

And the central idea that makes this computer work is this thing called stereographic projection. And basically, the concept is, how do you represent the three-dimensional image of the night sky that surrounds us onto a flat, portable, two-dimensional surface. The idea is actually relatively simple. Imagine that that Earth is at the center of the universe, and surrounding it is the sky projected onto a sphere. Each point on the surface of the sphere is mapped through the bottom pole, onto a flat surface, where it is then recorded.

So the North Star corresponds to the center of the device. The ecliptic, which is the path of the sun, moon, and planets correspond to an offset circle. The bright stars correspond to little daggers on the rete. And the altitude corresponds to the plate system. Now, the real genius of the astrolabe is not just the projection. The real genius is that it brings together two coordinate systems so they fit perfectly. There is the position of the sun, moon and planets on the movable rete. And then there is their location on the sky as seen from a certain latitude on the back plate. Okay?

So how would you use this device? Well, let me first back up for a moment. This is an astrolabe. Pretty impressive, isn't it? And so, this astrolabe is on loan from us from the Oxford School of -- Museum of History. And you can see the different components. This is the mater, the scales on the back. This is the rete. Okay. Do you see that? That's the movable part of the sky. And in the back you can see a spider web pattern. And that spider web pattern corresponds to the local coordinates in the sky. This is a rule device. And on the back are some other devices, measuring tools and scales, to be able to make some calculations. Okay?

You know, I've always wanted one of these. For my thesis I actually built one of these out of paper. And this one, this is a replica from a 15th-century device. And it's worth probably about three MacBook Pros. But a real one would cost about as much as my house, and the house next to it, and actually every house on the block, on both sides of the street, maybe a school thrown in, and some -- you know, a church. They are just incredibly expensive.

But let me show you how to work this device. So let's go to step one. First thing that you do is you select a star in the night sky, if you're telling time at night. So, tonight, if it's clear you'll be able to see the summer triangle. And there is a bright star called Deneb. So let's select Deneb. Second, is you measure the altitude of Deneb. So, step two, I hold the device up, and then I sight its altitude there so I can see it clearly now. And then I measure its altitude. So, it's about 26 degrees. You can't see it from over there. Step three is identify the star on the front of the device. Deneb is there. I can tell. Step four is I then move the rete, move the sky, so the altitude of the star corresponds to the scale on the back. Okay, so when that happens everything lines up. I have here a model of the sky that corresponds to the real sky. Okay? So, it is, in a sense, holding a model of the universe in my hands. And then finally, I take a rule, and move the rule to a date line which then tells me the time here. Right. So, that's how the device is used. (Laughter)

So, I know what you're thinking: "That's a lot of work, isn't it? Isn't it a ton of work to be able to tell the time?" as you glance at your iPod to just check out the time. But there is a difference between the two, because with your iPod you can tell -- or your iPhone, you can tell exactly what the time is, with precision. The way little Lewis would tell the time is by a picture of the sky. He would know where things would fit in the sky. He would not only know what time it was, he would also know where the sun would rise, and how it would move across the sky. He would know what time the sun would rise, and what time it would set. And he would know that for essentially every celestial object in the heavens.

So, in computer graphics and computer user interface design, there is a term called affordances. So, affordances are the qualities of an object that allow us to perform an action with it. And what the astrolabe does is it allows us, it affords us, to connect to the night sky, to look up into the night sky and be much more -- to see the visible and the invisible together. So, that's just one use. Incredible, there is probably 350, 400 uses. In fact, there is a text, and that has over a thousand uses of this first computer.

On the back there is scales and measurements for terrestrial navigation. You can survey with it. The city of Baghdad was surveyed with it. It can be used for calculating mathematical equations of all different types. And it would take a full university course to illustrate it. Astrolabes have an incredible history. They are over 2,000 years old. The concept of stereographic projection originated in 330 B.C.

And the astrolabes come in many different sizes and shapes and forms. There is portable ones. There is large display ones. And I think what is common to all astrolabes is that they are beautiful works of art. There is a quality of craftsmanship and precision that is just astonishing and remarkable.

Astrolabes, like every technology, do evolve over time. So, the earliest retes, for example, were very simple and primitive. And advancing retes became cultural emblems. This is one from Oxford. And I find this one really extraordinary because the rete pattern is completely symmetrical, and it accurately maps a completely asymmetrical, or random sky. How cool is that? This is just amazing.

So, would little Lewis have an astrolabe? Probably not one made of brass. He would have one made out of wood, or paper. And the vast majority of this first computer was a portable device that you could keep in the back of your pocket. So, what does the astrolabe inspire? Well, I think the first thing is that it reminds us just how resourceful people were, our forebears were, years and years ago. It's just an incredible device.

Every technology advances. Every technology is transformed and moved by others. And what we gain with a new technology, of course, is precision and accuracy. But what we lose, I think, is an accurate -- a felt sense of the sky, a sense of context. Knowing the sky, knowing your relationship with the sky, is the center of the real answer to knowing what time it is.

So, it's -- I think astrolabes are just remarkable devices. And so, what can you learn from these devices? Well, primarily that there is a subtle knowledge that we can connect with the world. And astrolabes return us to this subtle sense of how things all fit together, and also how we connect to the world. Thanks very much. (Applause)