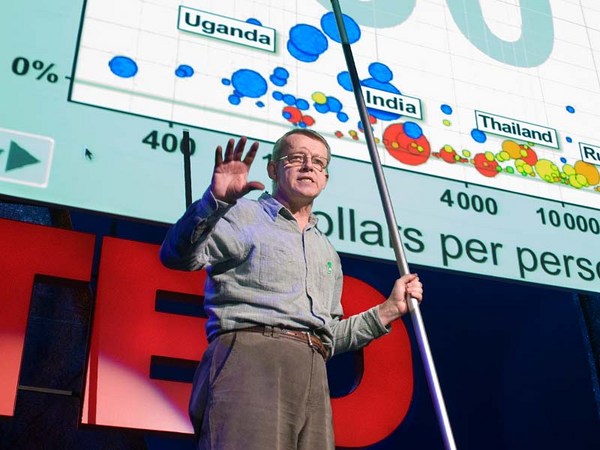

Last year at TED we aimed to try to clarify the overwhelming complexity and richness that we experience at the conference in a project called Big Viz. And the Big Viz is a collection of 650 sketches that were made by two visual artists. David Sibbet from The Grove, and Kevin Richards, from Autodesk, made 650 sketches that strive to capture the essence of each presenter's ideas. And the consensus was: it really worked. These sketches brought to life the key ideas, the portraits, the magic moments that we all experienced last year.

This year we were thinking, "Why does it work?" What is it about animation, graphics, illustrations, that create meaning? And this is an important question to ask and answer because the more we understand how the brain creates meaning, the better we can communicate, and, I also think, the better we can think and collaborate together. So this year we're going to visualize how the brain visualizes.

Cognitive psychologists now tell us that the brain doesn't actually see the world as it is, but instead, creates a series of mental models through a collection of "Ah-ha moments," or moments of discovery, through various processes.

The processing, of course, begins with the eyes. Light enters, hits the back of the retina, and is circulated, most of which is streamed to the very back of the brain, at the primary visual cortex. And primary visual cortex sees just simple geometry, just the simplest of shapes. But it also acts like a kind of relay station that re-radiates and redirects information to many other parts of the brain. As many as 30 other parts that selectively make more sense, create more meaning through the kind of "Ah-ha" experiences. We're only going to talk about three of them.

So the first one is called the ventral stream. It's on this side of the brain. And this is the part of the brain that will recognize what something is. It's the "what" detector. Look at a hand. Look at a remote control. Chair. Book. So that's the part of the brain that is activated when you give a word to something.

A second part of the brain is called the dorsal stream. And what it does is locates the object in physical body space. So if you look around the stage here you'll create a kind of mental map of the stage. And if you closed your eyes you'd be able to mentally navigate it. You'd be activating the dorsal stream if you did that.

The third part that I'd like to talk about is the limbic system. And this is deep inside of the brain. It's very old, evolutionarily. And it's the part that feels. It's the kind of gut center, where you see an image and you go, "Oh! I have a strong or emotional reaction to whatever I'm seeing."

So the combination of these processing centers help us make meaning in very different ways. So what can we learn about this? How can we apply this insight? Well, again, the schematic view is that the eye visually interrogates what we look at. The brain processes this in parallel, the figments of information asking a whole bunch of questions to create a unified mental model.

So, for example, when you look at this image a good graphic invites the eye to dart around, to selectively create a visual logic. So the act of engaging, and looking at the image creates the meaning. It's the selective logic. Now we've augmented this and spatialized this information. Many of you may remember the magic wall that we built in conjunction with Perceptive Pixel where we quite literally create an infinite wall. And so we can compare and contrast the big ideas. So the act of engaging and creating interactive imagery enriches meaning. It activates a different part of the brain. And then the limbic system is activated when we see motion, when we see color, and there are primary shapes and pattern detectors that we've heard about before.

So the point of this is what? We make meaning by seeing, by an act of visual interrogation. The lessons for us are three-fold. First, use images to clarify what we're trying to communicate. Secondly make those images interactive so that we engage much more fully. And the third is to augment memory by creating a visual persistence. These are techniques that can be used to be -- that can be applied in a wide range of problem solving.

So the low-tech version looks like this. And, by the way, this is the way in which we develop and formulate strategy within Autodesk, in some of our organizations and some of our divisions. What we literally do is have the teams draw out the entire strategic plan on one giant wall. And it's very powerful because everyone gets to see everything else. There's always a room, always a place to be able to make sense of all of the components in the strategic plan.

This is a time-lapse view of it. You can ask the question, "Who's the boss?" You'll be able to figure that out. (Laughter) So the act of collectively and collaboratively building the image transforms the collaboration. No Powerpoint is used in two days. But instead the entire team creates a shared mental model that they can all agree on and move forward on.

And this can be enhanced and augmented with some emerging digital technology. And this is our great unveiling for today. And this is an emerging set of technologies that use large-screen displays with intelligent calculation in the background to make the invisible visible. Here what we can do is look at sustainability, quite literally. So a team can actually look at all the key components that heat the structure and make choices and then see the end result that is visualized on this screen.

So making images meaningful has three components. The first again, is making ideas clear by visualizing them. Secondly, making them interactive. And then thirdly, making them persistent. And I believe that these three principles can be applied to solving some of the very tough problems that we face in the world today. Thanks so much.

(Applause)