Last year here at TED I asked you to give me your data, to put your data on the web, on the basis that if people put data onto the web -- government data, scientific data, community data, whatever it is -- it will be used by other people to do wonderful things, in ways that they never could have imagined.

So, today I'm back just to show you a few things, to show you, in fact, there is an open data movement afoot, now, around the world. The cry of "Raw data now!" which I made people make in the auditorium, was heard around the world. So, let's roll the video.

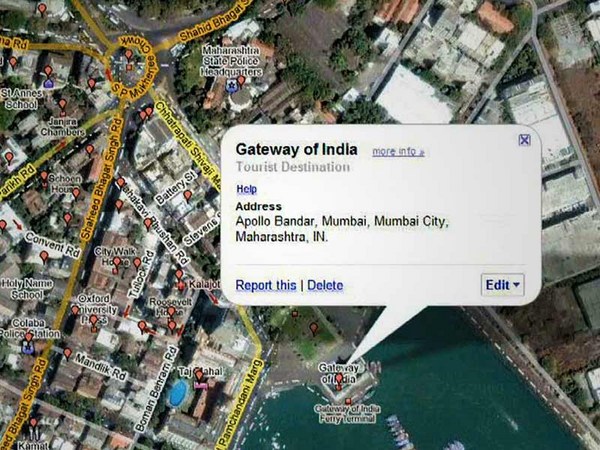

A classic story, the first one which lots of people picked up, was when in March -- on March 10th in fact, soon after TED -- Paul Clarke, in the U.K. government, blogged, "Oh, I've just got some raw data. Here it is, it's about bicycle accidents." Two days it took the Times Online to make a map, a mashable map -- we call these things mash-ups -- a mashed-up user interface that allows you to go in there and have a look and find out whether your bicycle route to work was affected.

Here's more data, traffic survey data, again, put out by the U.K. government, and because they put it up using the Linked Data standards, then a user could just make a map, just by clicking.

Does this data affect things? Well, let's get back to 2008. Look at Zanesville, Ohio. Here's a map a lawyer made. He put on it the water plant, and which houses are there, which houses have been connected to the water. And he got, from other data sources, information to show which houses are occupied by white people. Well, there was too much of a correlation, he felt, between which houses were occupied by white people and which houses had water, and the judge was not impressed either. The judge was not impressed to the tune of 10.9 million dollars. That's the power of taking one piece of data, another piece of data, putting it together, and showing the result.

Let's look at some data from the U.K. now. This is U.K. government data, a completely independent site, Where Does My Money Go. It allows anybody to go there and burrow down. You can burrow down by a particular type of spending, or you can go through all the different regions and compare them. So, that's happening in the U.K. with U.K. government data.

Yes, certainly you can do it over here. Here's a site which allows you to look at recovery spending in California. Take an arbitrary example, Long Beach, California, you can go and have a look at what recovery money they've been spending on different things such as energy.

In fact, this is the graph of the number of data sets in the repositories of data.gov, and data.gov.uk. And I'm delighted to see a great competition between the U.K. in blue, and the U.S. in red.

How can you use this stuff? Well, for example, if you have lots of data about places you can take, from a postcode -- which is like a zip plus four -- for a specific group of houses, you can make paper, print off a paper which has got very, very specific things about the bus stops, the things specifically near you.

On a larger scale, this is a mash-up of the data which was released about the Afghan elections. It allows you to set your own criteria for what sort of things you want to look at. The red circles are polling stations, selected by your criteria. And then you can select also other things on the map to see what other factors, like the threat level. So, that was government data.

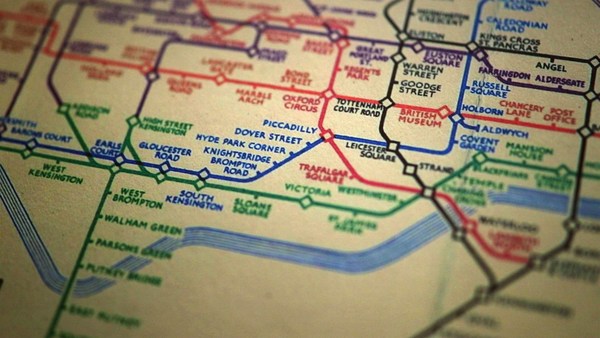

I also talked about community-generated data -- in fact I edited some. This is the wiki map, this is the Open Street Map. "Terrace Theater" I actually put on the map because it wasn't on the map before TED last year. I was not the only person editing the open street map. Each flash on this visualization -- put together by ITO World -- shows an edit in 2009 made to the Open Street Map. Let's now spin the world during the same year. Every flash is an edit. Somebody somewhere looking at the Open Street Map, and realizing it could be better. You can see Europe is ablaze with updates. Some places, perhaps not as much as they should be.

Here focusing in on Haiti. The map of Port au-Prince at the end of 2009 was not all it could be, not as good as the map of California. Fortunately, just after the earthquake, GeoEye, a commercial company, released satellite imagery with a license, which allowed the open-source community to use it. This is January, in time lapse, of people editing ... that's the earthquake. After the earthquake, immediately, people all over the world, mappers who wanted to help, and could, looked at that imagery, built the map, quickly building it up.

We're focusing now on Port-au-Prince. The light blue is refugee camps these volunteers had spotted from the [satellite images]. So, now we have, immediately, a real-time map showing where there are refugee camps -- rapidly became the best map to use if you're doing relief work in Port-au-Prince. Witness the fact that it's here on this Garmin device being used by rescue team in Haiti.

There's the map showing, on the left-hand side, that hospital -- actually that's a hospital ship. This is a real-time map that shows blocked roads, damaged buildings, refugee camps -- it shows things that are needed [for rescue and relief work].

So, if you've been involved in that at all, I just wanted to say: Whatever you've been doing, whether you've just been chanting, "Raw data now!" or you've been putting government or scientific data online, I just wanted to take this opportunity to say: Thank you very much, and we have only just started! (Applause)