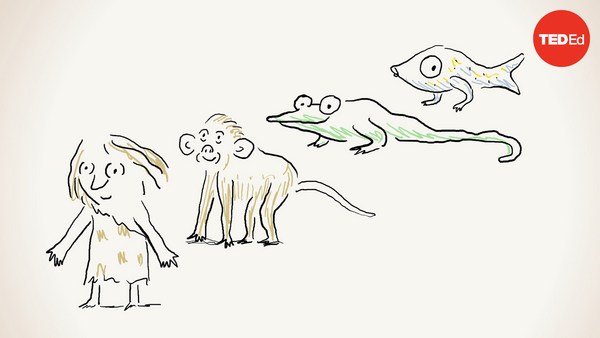

The animal kingdom boasts an incredible diversity of eyes. Some rotate independently, while others have squiggly-shaped pupils. Some have protective lids, others squirt blood. But which creature has the best sight? Which sees best in the darkness? Which sees the most detail? Which animal sees the most color? And finally, which detects motion the fastest?

All eyes take in sensory stimuli in the form of waves of light. To convert these into everything we see, eyes focus incoming light onto photoreceptors. These cells translate light into neural signals and send them to the brain, where they’re finally processed.

The eyes that see best in darkness are those that capture as much available light as possible. Colossal squids have soccer-ball-sized eyes— the largest known in existence. These may help them spot the faint glow of sperm whales as they disturb light-producing organisms. Some fish have eyes that are unique among vertebrates because they use mirrors. For the brownsnout spookfish, each eye has an upward-facing lens and a downward-pointing mirror composed of tiny crystal plates that efficiently gather light. They can see up and down simultaneously, and may perceive distinct shapes, even in the ocean’s depths. Back on solid ground, arctic reindeer have adaptations to deal with months of darkness. The backs of reindeer eyes change color, from gold in summer to blue in winter. Their blue-backed eyes are about 1,000 times more sensitive to light. This may allow reindeer to recognize important things in the snow like urine and lichen.

When it comes to the sharpest vision, birds of prey soar above the competition. To capture the most detail, an animal must have lots of photoreceptors in its eye, as well as increased visual processing power. Raptors have an especially deep fovea— a depression in the back of their eye that fits more photoreceptors. So, Peregrine falcons have vision that’s more than twice as sharp as a human’s. They’re able to zero in on a rabbit from more than three kilometers away.

When crowning the creature with the best color vision, the picture gets complicated. Different photoreceptors are sensitive to specific waves of light, meaning the colors we see are largely determined by what kinds of photoreceptors we have. Presumably, the more types of color photoreceptors an animal has, the better its color vision. Dogs have just two types. Humans have three. And we are far outdone by some birds, fishes, and insects. Bluebottle butterflies have at least 15 types of photoreceptors. Seven of them are attuned to distinct blues and greens, which researchers think might help them track each other during high-speed chases. Mantis shrimp have a whopping 16 kinds of photoreceptors, with five reserved just for the ultraviolet, or UV, spectrum, which humans can’t see. But experiments suggest that the mantis shrimp’s ability to discriminate between colors is more limited than you might expect. Exactly how they use their complex eyes is a mystery. Meanwhile, with just four kinds of color photoreceptors, goldfish actually excel at discerning subtle differences in shades.

Finally, insects have mastered the ability to see the world... on the fly. The fastest motion vision requires photoreceptors that quickly sense changes in light, and a brain that rapidly processes the information. A movie shot at 24 frames per second gives us the perception of near seamless motion. But insects would see a slideshow. Fly photoreceptors register changes 10 times faster than we do, making them especially hard to catch.

These animals have some of the best vision we know of, but there's no winner across the board. Each category has different top contenders because vision requires tradeoffs. So, some eyes are highly specialized, while others, like ours, perform decently in many categories. From eyes the size of soccer balls to those that see in UV— the ways of looking at the world are as varied as the life forms in it.