Juana Ramírez de Asbaje sat before a panel of prestigious theologians, jurists, and mathematicians. The viceroy of New Spain had invited them to test the young woman’s knowledge by posing the most difficult questions they could muster. But Juana successfully answered every challenge, from complicated equations to philosophical queries. Observers would later liken the scene to “a royal galleon fending off a few canoes.”

The woman who faced this interrogation was born in the mid-17th century. At that time, Mexico had been a Spanish colony for over a century, leading to a complex and stratified class system. Juana’s maternal grandparents were born in Spain, making them members of Mexico’s most esteemed class. But Juana was born out of wedlock, and her father – a Spanish military captain – left her mother, Doña Isabel, to raise Juana and her sisters alone. Fortunately, her grandfather’s moderate means ensured the family a comfortable existence. And Doña Isabel set a strong example for her daughters, successfully managing one of her father’s two estates, despite her illiteracy and the misogyny of the time.

It was perhaps this precedent that inspired Juana’s lifelong confidence. At age three, she secretly followed her older sister to school. When she later learned that higher education was open only to men, she begged her mother to let her attend in disguise. Her request denied, Juana found solace in her grandfather’s private library. By early adolescence, she’d mastered philosophical debate, Latin, and the Aztec language Nahuatl.

Juana’s precocious intellect attracted attention from the royal court in Mexico City, and when she was sixteen, the viceroy and his wife took her in as their lady-in-waiting. Here, her plays and poems alternately dazzled and outraged the court. Her provocative poem Foolish Men infamously criticized sexist double standards, decrying how men corrupt women while blaming them for immorality. Despite its controversy, her work still inspired adoration, and numerous proposals. But Juana was more interested in knowledge than marriage. And in the patriarchal society of the time, there was only one place she could find it.

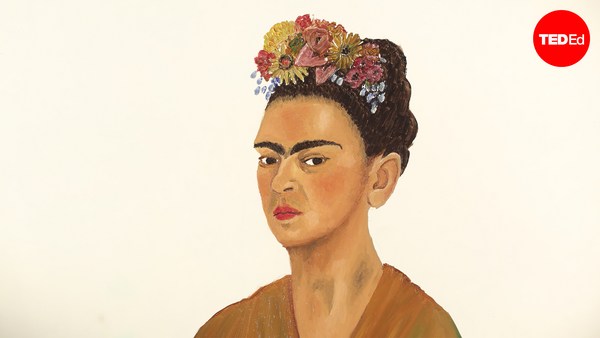

The Church, while still under the zealous influence of the Spanish Inquisition, would allow Juana to retain her independence and respectability while remaining unmarried. At age 20, she entered the Hieronymite Convent of Santa Paula and took on her new name: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

For years, Sor Juana was considered a prized treasure of the church. She wrote dramas, comedies, and treatises on philosophy and mathematics, in addition to religious music and poetry. She accrued a massive library, and was visited by many prominent scholars. While serving as the convent’s treasurer and archivist, she also protected the livelihoods of her niece and sisters from men who tried to exploit them.

But her outspokenness ultimately brought her into conflict with her benefactors. In 1690, a bishop published Sor Juana’s private critique of a respected sermon. In the publication, he admonished Sor Juana to devote herself to prayer rather than debate. She replied that God would not have given women intellect if he did not want them to use it. The exchange caught the attention of the conservative Archbishop of Mexico. Slowly, Sor Juana was stripped of her prestige, forced to sell her books and give up writing. Furious at this censorship, but unwilling to leave the church, she bitterly renewed her vows. In her last act of defiance, she signed them “I, the worst of all,” in her own blood.

Deprived of scholarship, Sor Juana threw herself into charity work, and in 1695, she died of an illness she contracted while nursing her sisters. Today, Sor Juana has been recognized as the first feminist in the Americas. She’s the subject of countless documentaries, novels, and operas, and appears on Mexico’s 200-peso banknote. In the words of Nobel laureate Octavio Paz: “It is not enough to say that Sor Juana’s work is a product of history; we must add that history is also a product of her work.”