I'd like to start by asking you all to go to your happy place, please. Yes, your happy place, I know you've got one even if it's fake.

(Laughter)

OK, so, comfortable? Good.

Now I'd like to you to mentally answer the following questions. Is there any strip lighting in your happy place? Any plastic tables? Polyester flooring? Mobile phones? No? I think we all know that our happy place is meant to be somewhere natural, outdoors -- on a beach, fireside. We'll be reading or eating or knitting. And we're surrounded by natural light and organic elements. Natural things make us happy. And happiness is a great motivator; we strive for happiness. Perhaps that's why we're always redesigning everything, in the hopes that our solutions might feel more natural. So let's start there -- with the idea that good design should feel natural.

Your phone is not very natural. And you probably think you're addicted to your phone, but you're really not. We're not addicted to devices, we're addicted to the information that flows through them. I wonder how long you would be happy in your happy place without any information from the outside world. I'm interested in how we access that information, how we experience it. We're moving from a time of static information, held in books and libraries and bus stops, through a period of digital information, towards a period of fluid information, where your children will expect to be able to access anything, anywhere at any time, from quantum physics to medieval viticulture, from gender theory to tomorrow's weather, just like switching on a lightbulb -- Imagine that.

Humans also like simple tools. Your phone is not a very simple tool. A fork is a simple tool.

(Laughter)

And we don't like them made of plastic, in the same way I don't really like my phone very much -- it's not how I want to experience information.

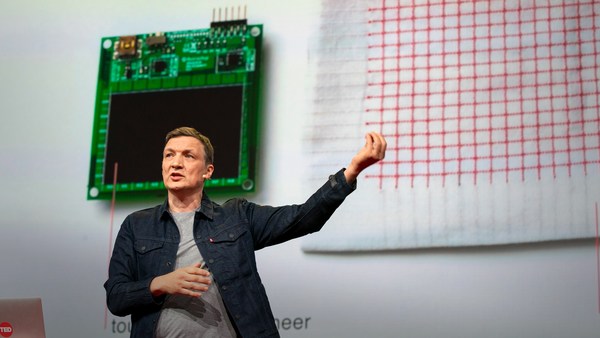

I think there are better solutions than a world mediated by screens. I don't hate screens, but I don't feel -- and I don't think any of us feel that good about how much time we spend slouched over them. Fortunately, the big tech companies seem to agree. They're actually heavily invested in touch and speech and gesture, and also in senses -- things that can turn dumb objects, like cups, and imbue them with the magic of the Internet, potentially turning this digital cloud into something we might touch and move.

The parents in crisis over screen time need physical digital toys teaching their kids to read, as well as family-safe app stores. And I think, actually, that's already really happening.

Reality is richer than screens. For example, I love books. For me they are time machines -- atoms and molecules bound in space, from the moment of their creation to the moment of my experience. But frankly, the content's identical on my phone. So what makes this a richer experience than a screen? I mean, scientifically. We need screens, of course. I'm going to show film, I need the enormous screen. But there's more than you can do with these magic boxes. Your phone is not the Internet's door bitch.

(Laughter)

We can build things -- physical things, using physics and pixels, that can integrate the Internet into the world around us. And I'm going to show you a few examples of those.

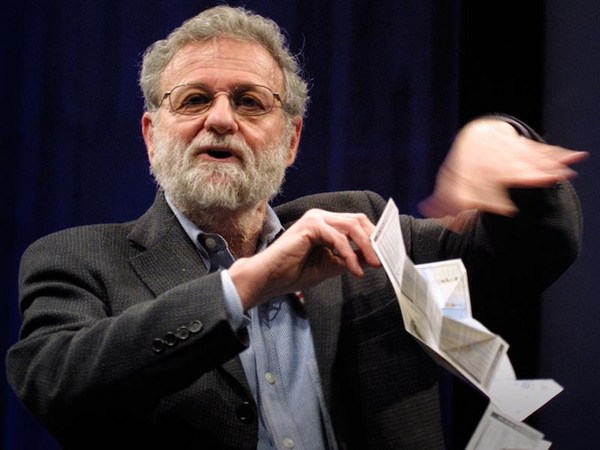

A while ago, I got to work with a design agency, Berg, on an exploration of what the Internet without screens might actually look like. And they showed us a range ways that light can work with simple senses and physical objects to really bring the Internet to life, to make it tangible. Like this wonderfully mechanical YouTube player. And this was an inspiration to me.

Next I worked with the Japanese agency, AQ, on a research project into mental health. We wanted to create an object that could capture the subjective data around mood swings that's so essential to diagnosis. This object captures your touch, so you might press it very hard if you're angry, or stroke it if you're calm. It's like a digital emoji stick. And then you might revisit those moments later, and add context to them online. Most of all, we wanted to create an intimate, beautiful thing that could live in your pocket and be loved.

The binoculars are actually a birthday present for the Sydney Opera House's 40th anniversary. Our friends at Tellart in Boston brought over a pair of street binoculars, the kind you might find on the Empire State Building, and they fitted them with 360-degree views of other iconic world heritage sights --

(Laughter)

using Street View. And then we stuck them under the steps. So, they became this very physical, simple reappropriation, or like a portal to these other icons. So you might see Versailles or Shackleton's Hut. Basically, it's virtual reality circa 1955.

(Laughter)

In our office we use hacky sacks to exchange URLs. This is incredibly simple, it's like your Opal card. You basically put a website on the little chip in here, and then you do this and ... bosh! -- the website appears on your phone. It's about 10 cents.

Treehugger is a project that we're working on with Grumpy Sailor and Finch, here in Sydney. And I'm very excited about what might happen when you pull the phones apart and you put the bits into trees, and that my children might have an opportunity to visit an enchanted forest guided by a magic wand, where they could talk to digital fairies and ask them questions, and be asked questions in return. As you can see, we're at the cardboard stage with this one.

(Laughter)

But I'm very excited by the possibility of getting kids back outside without screens, but with all the powerful magic of the Internet at their fingertips. And we hope to have something like this working by the end of the year.

So let's recap. Humans like natural solutions. Humans love information. Humans need simple tools. These principles should underpin how we design for the future, not just for the Internet. You may feel uncomfortable about the age of information that we're moving into. You may feel challenged, rather than simply excited. Guess what? Me too. It's a really extraordinary period of human history.

We are the people that actually build our world, there are no artificial intelligences... yet.

(Laughter)

It's us -- designers, architects, artists, engineers. And if we challenge ourselves, I think that actually we can have a happy place filled with the information we love that feels as natural and as simple as switching on lightbulb. And although it may seem inevitable, that what the public wants is watches and websites and widgets, maybe we could give a bit of thought to cork and light and hacky sacks.

Thank you very much.

(Applause)