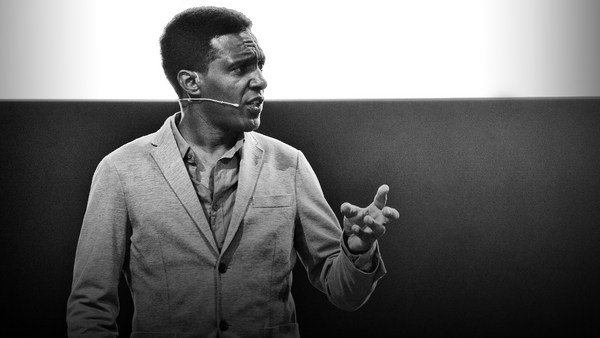

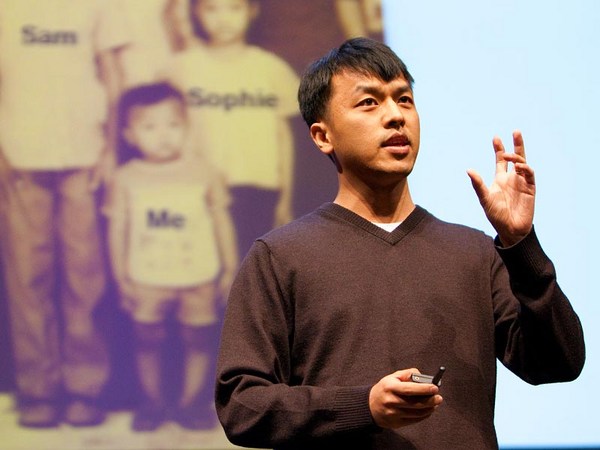

These are some photos of me volunteering in a Cambodian orphanage in 2006. When these photos were taken, I thought I was doing a really good thing and that I was really helping those kids. I had a lot to learn.

It all started for me when I was 19 years old and went backpacking through Southeast Asia. When I reached Cambodia, I felt uncomfortable being on holiday surrounded by so much poverty and wanted to do something to give back. So I visited some orphanages and donated some clothes and books and some money to help the kids that I met.

But one of the orphanages I visited was desperately poor. I had never encountered poverty like that before in my life. They didn't have funds for enough food, clean water or medical treatment, and the sad little faces on those kids were heartbreaking. So I was compelled to do something more to help. I fund-raised in Australia and returned to Cambodia the following year to volunteer at the orphanage for a few months. I taught English and bought water filters and food and took all of the kids to the dentist for the first time in their lives.

But over the course of the next year, I came to discover that this orphanage that I had been supporting was terribly corrupt. The director had been embezzling every cent donated to the orphanage, and in my absence, the children were suffering such gross neglect that they were forced to catch mice to feed themselves. I also found out later that the director had been physically and sexually abusing the kids. I couldn't bring myself to turn my back on children who I had come to know and care about and return to my life in Australia. So I worked with a local team and the local authorities to set up a new orphanage and rescue the kids to give them a safe new home.

But this is where my story takes another unexpected turn. As I adjusted to my new life running an orphanage in Cambodia, (Khmer) I learned to speak Khmer fluently, which means that I learned to speak the Khmer language fluently. And when I could communicate properly with the kids, I began to uncover some strange things. Most of the children we had removed from the orphanage were not, in fact, orphans at all. They had parents, and the few that were orphaned had other living relatives, like grandparents and aunties and uncles and other siblings.

So why were these children living in an orphanage when they weren't orphans? Since 2005, the number of orphanages in Cambodia has risen by 75 percent, and the number of children living in Cambodian orphanages has nearly doubled, despite the fact that the vast majority of children living in these orphanages are not orphans in the traditional sense. They're children from poor families. So if the vast majority of children living in orphanages are not orphans, then the term "orphanage" is really just a euphemistic name for a residential care institution. These institutions go by other names as well, like "shelters," "safe houses," "children's homes," "children's villages," even "boarding schools."

And this problem is not just confined to Cambodia. This map shows some of the countries that have seen a dramatic increase in the numbers of residential care institutions and the numbers of children being institutionalized. In Uganda, for example, the number of children living in institutions has increased by more than 1,600 percent since 1992. And the problems posed by putting kids into institutions don't just pertain to the corrupt and abusive institutions like the one that I rescued the kids from. The problems are with all forms of residential care.

Over 60 years of international research has shown us that children who grow up in institutions, even the very best institutions, are at serious risk of developing mental illnesses, attachment disorders, growth and speech delays, and many will struggle with an inability to reintegrate back into society later in life and form healthy relationships as adults. These kids grow up without any model of family or of what good parenting looks like, so they then can struggle to parent their own children. So if you institutionalize large numbers of children, it will affect not only this generation, but also the generations to come.

We've learned these lessons before in Australia. It's what happened to our "Stolen Generations," the indigenous children who were removed from their families with the belief that we could do a better job of raising their children.

Just imagine for a moment what residential care would be like for a child. Firstly, you have a constant rotation of caregivers, with somebody new coming on to the shift every eight hours. And then on top of that you have a steady stream of visitors and volunteers coming in, showering you in the love and affection you're craving and then leaving again, evoking all of those feelings of abandonment, and proving again and again that you are not worthy of being loved.

We don't have orphanages in Australia, the USA, the UK anymore, and for a very good reason: one study has shown that young adults raised in institutions are 10 times more likely to fall into sex work than their peers, 40 times more likely to have a criminal record, and 500 times more likely to take their own lives. There are an estimated eight million children around the world living in institutions like orphanages, despite the fact that around 80 percent of them are not orphans. Most have families who could be caring for them if they had the right support.

But for me, the most shocking thing of all to realize is what's contributing to this boom in the unnecessary institutionalization of so many children: it's us -- the tourists, the volunteers and the donors. It's the well-meaning support from people like me back in 2006, who visit these children and volunteer and donate, who are unwittingly fueling an industry that exploits children and tears families apart.

It's really no coincidence that these institutions are largely set up in areas where tourists can most easily be lured in to visit and volunteer in exchange for donations. Of the 600 so-called orphanages in Nepal, over 90 percent of them are located in the most popular tourist hotspots. The cold, hard truth is, the more money that floods in in support of these institutions, the more institutions open and the more children are removed from their families to fill their beds. It's just the laws of supply and demand.

I had to learn all of these lessons the hard way, after I had already set up an orphanage in Cambodia. I had to eat a big piece of humble pie to admit that I had made a mistake and inadvertently become a part of the problem. I had been an orphanage tourist, a voluntourist. I then set up my own orphanage and facilitated orphanage tourism in order to generate funds for my orphanage, before I knew better. What I came to learn is that no matter how good my orphanage was, it was never going to give those kids what they really needed: their families.

I know that it can feel incredibly depressing to learn that helping vulnerable children and overcoming poverty is not as simple as we've all been led to believe it should be. But thankfully, there is a solution. These problems are reversible and preventable, and when we know better, we can do better.

The organization that I run today, the Cambodian Children's Trust, is no longer an orphanage. In 2012, we changed the model in favor of family-based care. I now lead an amazing team of Cambodian social workers, nurses and teachers. Together, we work within communities to untangle a complex web of social issues and help Cambodian families escape poverty. Our primary focus is on preventing some of the most vulnerable families in our community from being separated in the first place. But in cases where it's not possible for a child to live with its biological family, we support them in foster care. Family-based care is always better than placing a child in an institution.

Do you remember that first photo that I showed you before? See that girl who is just about to catch the ball? Her name is Torn She's a strong, brave and fiercely intelligent girl. But in 2006, when I first met her living in that corrupt and abusive orphanage, she had never been to school. She was suffering terrible neglect, and she yearned desperately for the warmth and love of her mother. But this is a photo of Torn today with her family. Her mother now has a secure job, her siblings are doing well in high school and she is just about to finish her nursing degree at university. For Torn's family --

(Applause)

for Torn's family, the cycle of poverty has been broken. The family-based care model that we have developed at CCT has been so successful, that it's now being put forward by UNICEF Cambodia and the Cambodian government as a national solution to keep children in families. And one of the best --

(Applause)

And one of the best ways that you can help to solve this problem is by giving these eight million children a voice and become an advocate for family-based care.

If we work together to raise awareness, we can make sure the world knows that we need to put an end to the unnecessary institutionalization of vulnerable children. How do we achieve that? By redirecting our support and our donations away from orphanages and residential care institutions towards organizations that are committed to keeping children in families.

I believe we can make this happen in our lifetime, and as a result, we will see developing communities thrive and ensure that vulnerable children everywhere have what all children need and deserve: a family.

Thank you.

(Applause)