This is an equipment graveyard. It's a typical final resting place for medical equipment from hospitals in Africa. Now, why is this? Most of the medical devices used in Africa are imported, and quite often, they're not suitable for local conditions. They may require trained staff that aren't available to operate and maintain and repair them; they may not be able to withstand high temperatures and humidity; and they usually require a constant and reliable supply of electricity.

An example of a medical device that may have ended up in an equipment graveyard at some point is an ultrasound monitor to track the heart rate of unborn babies. This is the standard of care in rich countries. In low-resource settings, the standard of care is often a midwife listening to the baby's heart rate through a horn. Now, this approach has been around for more than a century. It's very much dependent on the skill and the experience of the midwife.

Two young inventors from Uganda visited an antenatal clinic at a local hospital a few years ago, when they were students in information technology. They noticed that quite often, the midwife was not able to hear any heart rate when trying to listen to it through this horn. So they invented their own fetal heart rate monitor. They adapted the horn and connected it to a smartphone. An app on the smartphone records the heart rate, analyzes it and provides the midwife with a range of information on the status of the baby. These inventors --

(Applause)

are called Aaron Tushabe and Joshua Okello.

Another inventor, Tendekayi Katsiga, was working for an NGO in Botswana that manufactured hearing aids. Now, he noticed that these hearing aids needed batteries that needed replacement, very often at a cost that was not affordable for most of the users that he knew. In response, and being an engineer, Tendekayi invented a solar-powered battery charger with rechargeable batteries, that could be used in these hearing aids. He cofounded a company called Deaftronics, which now manufactures the Solar Ear, which is a hearing aid powered by his invention.

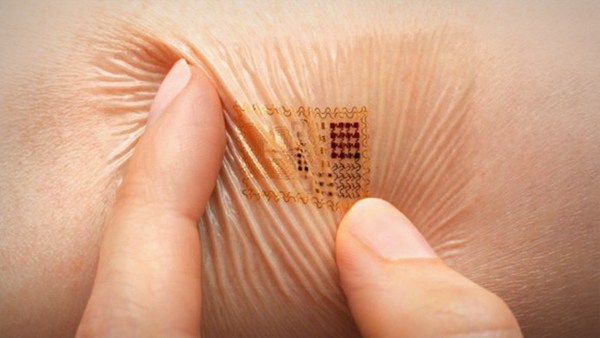

My colleague, Sudesh Sivarasu, invented a smart glove for people who have suffered from leprosy. Even though their disease may have been cured, the resulting nerve damage will have left many of them without a sense of touch in their hands. This puts them at risk of injury. The glove has sensors to detect temperature and pressure and warn the user. It effectively serves as an artificial sense of touch and prevents injury. Sudesh invented this glove after observing former leprosy patients as they carried out their day-to-day activities, and he learned about the risks and the hazards in their environment.

Now, the inventors that I've mentioned integrated engineering with healthcare. This is what biomedical engineers do. At the University of Cape Town, we run a course called Health Innovation and Design. It's taken by many of our graduate students in biomedical engineering. The aim of the course is to introduce these students to the philosophy of the design world. The students are encouraged to engage with communities as they search for solutions to health-related problems.

One of the communities that we work with is a group of elderly people in Cape Town. A recent class project had the task of addressing hearing loss in these elderly people. The students, many of them being engineers, set out believing that they would design a better hearing aid. They spent time with the elderly, chatted to their healthcare providers and their caregivers. They soon realized that, actually, adequate hearing aids already existed, but many of the elderly who needed them and had access to them didn't have them. And many of those who had hearing aids wouldn't wear them. The students realized that many of these elderly people were in denial of their hearing loss. There's a stigma attached to wearing a hearing aid. They also discovered that the environment in which these elderly people lived did not accommodate their hearing loss. For example, their homes and their community center were filled with echoes that interfered with their hearing. So instead of developing and designing a new and better hearing aid, the students did an audit of the environment, with a view to improving the acoustics. They also devised a campaign to raise awareness of hearing loss and to counter the stigma attached to wearing a hearing aid. Now, this often happens when one pays attention to the user -- in this case, the elderly -- and their needs and their context. One often has to move away from the focus of technology and reformulate the problem.

This approach to understanding a problem through listening and engaging is not new, but it often isn't followed by engineers, who are intent on developing technology. One of our students has a background in software engineering. He had often created products for clients that the client ultimately did not like. When a client would reject a product, it was common at his company to proclaim that the client just didn't know what they wanted. Having completed the course, the student fed back to us that he now realized that it was he who hadn't understood what the client wanted. Another student gave us feedback that she had learned to design with empathy, as opposed to designing for functionality, which is what her engineering education had taught her.

So what all of this illustrates is that we're often blinded to real needs in our pursuit of technology. But we need technology. We need hearing aids. We need fetal heart rate monitors.

So how do we create more medical device success stories from Africa? How do we create more inventors, rather than relying on a few exceptional individuals who are able to perceive real needs and respond in ways that work? Well, we focus on needs and people and context. "But this is obvious," you might say, "Of course context is important."

But Africa is a diverse continent, with vast disparities in health and wealth and income and education. If we assume that our engineers and inventors already know enough about the different African contexts to be able to solve the problems of our different communities and our most marginalized communities, then we might get it wrong. But then, if we on the African continent don't necessarily know enough about it, then perhaps anybody with the right level of skill and commitment could fly in, spend some time listening and engaging and fly out knowing enough to invent for Africa.

But understanding context is not about a superficial interaction. It's about deep engagement and an immersion in the realities and the complexities of our context. And we in Africa are already immersed. We already have a strong and rich base of knowledge from which to start finding solutions to our own problems. So let's not rely too much on others when we live on a continent that is filled with untapped talent.

Thank you.

(Applause)