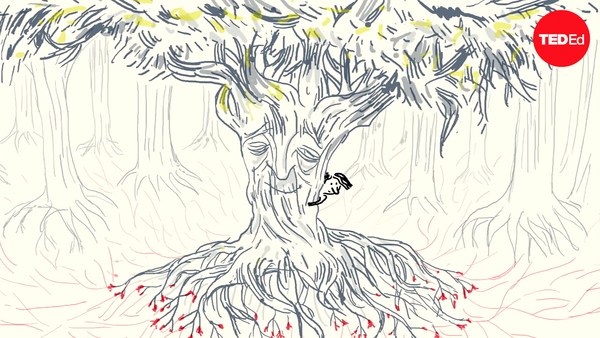

Imagine you're walking through a forest. I'm guessing you're thinking of a collection of trees, what we foresters call a stand, with their rugged stems and their beautiful crowns. Yes, trees are the foundation of forests, but a forest is much more than what you see, and today I want to change the way you think about forests. You see, underground there is this other world, a world of infinite biological pathways that connect trees and allow them to communicate and allow the forest to behave as though it's a single organism. It might remind you of a sort of intelligence.

How do I know this? Here's my story. I grew up in the forests of British Columbia. I used to lay on the forest floor and stare up at the tree crowns. They were giants. My grandfather was a giant, too. He was a horse logger, and he used to selectively cut cedar poles from the inland rainforest. Grandpa taught me about the quiet and cohesive ways of the woods, and how my family was knit into it. So I followed in grandpa's footsteps.

He and I had this curiosity about forests, and my first big "aha" moment was at the outhouse by our lake. Our poor dog Jigs had slipped and fallen into the pit. So grandpa ran up with his shovel to rescue the poor dog. He was down there, swimming in the muck. But as grandpa dug through that forest floor, I became fascinated with the roots, and under that, what I learned later was the white mycelium and under that the red and yellow mineral horizons. Eventually, grandpa and I rescued the poor dog, but it was at that moment that I realized that that palette of roots and soil was really the foundation of the forest.

And I wanted to know more. So I studied forestry. But soon I found myself working alongside the powerful people in charge of the commercial harvest. The extent of the clear-cutting was alarming, and I soon found myself conflicted by my part in it. Not only that, the spraying and hacking of the aspens and birches to make way for the more commercially valuable planted pines and firs was astounding. It seemed that nothing could stop this relentless industrial machine.

So I went back to school, and I studied my other world. You see, scientists had just discovered in the laboratory in vitro that one pine seedling root could transmit carbon to another pine seedling root. But this was in the laboratory, and I wondered, could this happen in real forests? I thought yes. Trees in real forests might also share information below ground. But this was really controversial, and some people thought I was crazy, and I had a really hard time getting research funding. But I persevered, and I eventually conducted some experiments deep in the forest, 25 years ago. I grew 80 replicates of three species: paper birch, Douglas fir, and western red cedar. I figured the birch and the fir would be connected in a belowground web, but not the cedar. It was in its own other world. And I gathered my apparatus, and I had no money, so I had to do it on the cheap. So I went to Canadian Tire --

(Laughter)

and I bought some plastic bags and duct tape and shade cloth, a timer, a paper suit, a respirator. And then I borrowed some high-tech stuff from my university: a Geiger counter, a scintillation counter, a mass spectrometer, microscopes. And then I got some really dangerous stuff: syringes full of radioactive carbon-14 carbon dioxide gas and some high pressure bottles of the stable isotope carbon-13 carbon dioxide gas. But I was legally permitted.

(Laughter)

Oh, and I forgot some stuff, important stuff: the bug spray, the bear spray, the filters for my respirator. Oh well.

The first day of the experiment, we got out to our plot and a grizzly bear and her cub chased us off. And I had no bear spray. But you know, this is how forest research in Canada goes.

(Laughter)

So I came back the next day, and mama grizzly and her cub were gone. So this time, we really got started, and I pulled on my white paper suit, I put on my respirator, and then I put the plastic bags over my trees. I got my giant syringes, and I injected the bags with my tracer isotope carbon dioxide gases, first the birch. I injected carbon-14, the radioactive gas, into the bag of birch. And then for fir, I injected the stable isotope carbon-13 carbon dioxide gas. I used two isotopes, because I was wondering whether there was two-way communication going on between these species. I got to the final bag, the 80th replicate, and all of a sudden mama grizzly showed up again. And she started to chase me, and I had my syringes above my head, and I was swatting the mosquitos, and I jumped into the truck, and I thought, "This is why people do lab studies."

(Laughter)

I waited an hour. I figured it would take this long for the trees to suck up the CO2 through photosynthesis, turn it into sugars, send it down into their roots, and maybe, I hypothesized, shuttle that carbon belowground to their neighbors. After the hour was up, I rolled down my window, and I checked for mama grizzly. Oh good, she's over there eating her huckleberries. So I got out of the truck and I got to work. I went to my first bag with the birch. I pulled the bag off. I ran my Geiger counter over its leaves. Kkhh! Perfect. The birch had taken up the radioactive gas. Then the moment of truth. I went over to the fir tree. I pulled off its bag. I ran the Geiger counter up its needles, and I heard the most beautiful sound. Kkhh! It was the sound of birch talking to fir, and birch was saying, "Hey, can I help you?" And fir was saying, "Yeah, can you send me some of your carbon? Because somebody threw a shade cloth over me." I went up to cedar, and I ran the Geiger counter over its leaves, and as I suspected, silence. Cedar was in its own world. It was not connected into the web interlinking birch and fir.

I was so excited, I ran from plot to plot and I checked all 80 replicates. The evidence was clear. The C-13 and C-14 was showing me that paper birch and Douglas fir were in a lively two-way conversation. It turns out at that time of the year, in the summer, that birch was sending more carbon to fir than fir was sending back to birch, especially when the fir was shaded. And then in later experiments, we found the opposite, that fir was sending more carbon to birch than birch was sending to fir, and this was because the fir was still growing while the birch was leafless. So it turns out the two species were interdependent, like yin and yang.

And at that moment, everything came into focus for me. I knew I had found something big, something that would change the way we look at how trees interact in forests, from not just competitors but to cooperators. And I had found solid evidence of this massive belowground communications network, the other world.

Now, I truly hoped and believed that my discovery would change how we practice forestry, from clear-cutting and herbiciding to more holistic and sustainable methods, methods that were less expensive and more practical. What was I thinking? I'll come back to that.

So how do we do science in complex systems like forests? Well, as forest scientists, we have to do our research in the forests, and that's really tough, as I've shown you. And we have to be really good at running from bears. But mostly, we have to persevere in spite of all the stuff stacked against us. And we have to follow our intuition and our experiences and ask really good questions. And then we've got to gather our data and then go verify. For me, I've conducted and published hundreds of experiments in the forest. Some of my oldest experimental plantations are now over 30 years old. You can check them out. That's how forest science works.

So now I want to talk about the science. How were paper birch and Douglas fir communicating? Well, it turns out they were conversing not only in the language of carbon but also nitrogen and phosphorus and water and defense signals and allelochemicals and hormones -- information. And you know, I have to tell you, before me, scientists had thought that this belowground mutualistic symbiosis called a mycorrhiza was involved. Mycorrhiza literally means "fungus root." You see their reproductive organs when you walk through the forest. They're the mushrooms. The mushrooms, though, are just the tip of the iceberg, because coming out of those stems are fungal threads that form a mycelium, and that mycelium infects and colonizes the roots of all the trees and plants. And where the fungal cells interact with the root cells, there's a trade of carbon for nutrients, and that fungus gets those nutrients by growing through the soil and coating every soil particle. The web is so dense that there can be hundreds of kilometers of mycelium under a single footstep. And not only that, that mycelium connects different individuals in the forest, individuals not only of the same species but between species, like birch and fir, and it works kind of like the Internet.

You see, like all networks, mycorrhizal networks have nodes and links. We made this map by examining the short sequences of DNA of every tree and every fungal individual in a patch of Douglas fir forest. In this picture, the circles represent the Douglas fir, or the nodes, and the lines represent the interlinking fungal highways, or the links.

The biggest, darkest nodes are the busiest nodes. We call those hub trees, or more fondly, mother trees, because it turns out that those hub trees nurture their young, the ones growing in the understory. And if you can see those yellow dots, those are the young seedlings that have established within the network of the old mother trees. In a single forest, a mother tree can be connected to hundreds of other trees. And using our isotope tracers, we have found that mother trees will send their excess carbon through the mycorrhizal network to the understory seedlings, and we've associated this with increased seedling survival by four times.

Now, we know we all favor our own children, and I wondered, could Douglas fir recognize its own kin, like mama grizzly and her cub? So we set about an experiment, and we grew mother trees with kin and stranger's seedlings. And it turns out they do recognize their kin. Mother trees colonize their kin with bigger mycorrhizal networks. They send them more carbon below ground. They even reduce their own root competition to make elbow room for their kids. When mother trees are injured or dying, they also send messages of wisdom on to the next generation of seedlings. So we've used isotope tracing to trace carbon moving from an injured mother tree down her trunk into the mycorrhizal network and into her neighboring seedlings, not only carbon but also defense signals. And these two compounds have increased the resistance of those seedlings to future stresses. So trees talk.

(Applause)

Thank you.

Through back and forth conversations, they increase the resilience of the whole community. It probably reminds you of our own social communities, and our families, well, at least some families.

(Laughter)

So let's come back to the initial point. Forests aren't simply collections of trees, they're complex systems with hubs and networks that overlap and connect trees and allow them to communicate, and they provide avenues for feedbacks and adaptation, and this makes the forest resilient. That's because there are many hub trees and many overlapping networks. But they're also vulnerable, vulnerable not only to natural disturbances like bark beetles that preferentially attack big old trees but high-grade logging and clear-cut logging. You see, you can take out one or two hub trees, but there comes a tipping point, because hub trees are not unlike rivets in an airplane. You can take out one or two and the plane still flies, but you take out one too many, or maybe that one holding on the wings, and the whole system collapses.

So now how are you thinking about forests? Differently?

(Audience) Yes.

Cool. I'm glad.

So, remember I said earlier that I hoped that my research, my discoveries would change the way we practice forestry. Well, I want to take a check on that 30 years later here in western Canada.

This is about 100 kilometers to the west of us, just on the border of Banff National Park. That's a lot of clear-cuts. It's not so pristine. In 2014, the World Resources Institute reported that Canada in the past decade has had the highest forest disturbance rate of any country worldwide, and I bet you thought it was Brazil. In Canada, it's 3.6 percent per year. Now, by my estimation, that's about four times the rate that is sustainable.

Now, massive disturbance at this scale is known to affect hydrological cycles, degrade wildlife habitat, and emit greenhouse gases back into the atmosphere, which creates more disturbance and more tree diebacks.

Not only that, we're continuing to plant one or two species and weed out the aspens and birches. These simplified forests lack complexity, and they're really vulnerable to infections and bugs. And as climate changes, this is creating a perfect storm for extreme events, like the massive mountain pine beetle outbreak that just swept across North America, or that megafire in the last couple months in Alberta.

So I want to come back to my final question: instead of weakening our forests, how can we reinforce them and help them deal with climate change? Well, you know, the great thing about forests as complex systems is they have enormous capacity to self-heal. In our recent experiments, we found with patch-cutting and retention of hub trees and regeneration to a diversity of species and genes and genotypes that these mycorrhizal networks, they recover really rapidly. So with this in mind, I want to leave you with four simple solutions. And we can't kid ourselves that these are too complicated to act on.

First, we all need to get out in the forest. We need to reestablish local involvement in our own forests. You see, most of our forests now are managed using a one-size-fits-all approach, but good forest stewardship requires knowledge of local conditions.

Second, we need to save our old-growth forests. These are the repositories of genes and mother trees and mycorrhizal networks. So this means less cutting. I don't mean no cutting, but less cutting.

And third, when we do cut, we need to save the legacies, the mother trees and networks, and the wood, the genes, so they can pass their wisdom onto the next generation of trees so they can withstand the future stresses coming down the road. We need to be conservationists.

And finally, fourthly and finally, we need to regenerate our forests with a diversity of species and genotypes and structures by planting and allowing natural regeneration. We have to give Mother Nature the tools she needs to use her intelligence to self-heal. And we need to remember that forests aren't just a bunch of trees competing with each other, they're supercooperators.

So back to Jigs. Jigs's fall into the outhouse showed me this other world, and it changed my view of forests. I hope today to have changed how you think about forests.

Thank you.

(Applause)