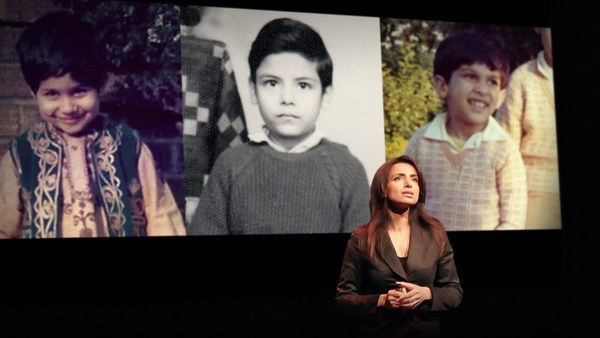

Last year, three of my family members were gruesomely murdered in a hate crime. It goes without saying that it's really difficult for me to be here today, but my brother Deah, his wife Yusor, and her sister Razan don't give me much of a choice. I'm hopeful that by the end of this talk you will make a choice, and join me in standing up against hate.

It's December 27, 2014: the morning of my brother's wedding day. He asks me to come over and comb his hair in preparation for his wedding photo shoot. A 23-year-old, six-foot-three basketball, particularly Steph Curry, fanatic --

(Laughter)

An American kid in dental school ready to take on the world. When Deah and Yusor have their first dance, I see the love in his eyes, her reciprocated joy, and my emotions begin to overwhelm me. I move to the back of the hall and burst into tears. And the second the song finishes playing, he beelines towards me, buries me into his arms and rocks me back and forth. Even in that moment, when everything was so distracting, he was attuned to me.

He cups my face and says, "Suzanne, I am who I am because of you. Thank you for everything. I love you."

About a month later, I'm back home in North Carolina for a short visit, and on the last evening, I run upstairs to Deah's room, eager to find out how he's feeling being a newly married man. With a big boyish smile he says, "I'm so happy. I love her. She's an amazing girl." And she is. At just 21, she'd recently been accepted to join Deah at UNC dental school. She shared his love for basketball, and at her urging, they started their honeymoon off attending their favorite team of the NBA, the LA Lakers. I mean, check out that form.

(Laughter)

I'll never forget that moment sitting there with him -- how free he was in his happiness. My littler brother, a basketball-obsessed kid, had become and transformed into an accomplished young man. He was at the top of his dental school class, and alongside Yusor and Razan, was involved in local and international community service projects dedicated to the homeless and refugees, including a dental relief trip they were planning for Syrian refugees in Turkey.

Razan, at just 19, used her creativity as an architectural engineering student to serve those around her, making care packages for the local homeless, among other projects. That is who they were.

Standing there that night, I take a deep breath and look at Deah and tell him, "I have never been more proud of you than I am in this moment." He pulls me into his tall frame, hugs me goodnight, and I leave the next morning without waking him to go back to San Francisco. That is the last time I ever hug him.

Ten days later, I'm on call at San Francisco General Hospital when I receive a barrage of vague text messages expressing condolences. Confused, I call my father, who calmly intones, "There's been a shooting in Deah's neighborhood in Chapel Hill. It's on lock-down. That's all we know." I hang up and quickly Google, "shooting in Chapel Hill." One hit comes up. Quote: "Three people were shot in the back of the head and confirmed dead on the scene." Something in me just knows. I fling out of my chair and faint onto the gritty hospital floor, wailing.

I take the first red-eye out of San Francisco, numb and disoriented. I walk into my childhood home and faint into my parents' arms, sobbing. I then run up to Deah's room as I did so many times before, just looking for him, only to find a void that will never be filled.

Investigation and autopsy reports eventually revealed the sequence of events. Deah had just gotten off the bus from class, Razan was visiting for dinner, already at home with Yusor. As they began to eat, they heard a knock on the door. When Deah opened it, their neighbor proceeded to fire multiple shots at him. According to 911 calls, the girls were heard screaming. The man turned towards the kitchen and fired a single shot into Yusor's hip, immobilizing her. He then approached her from behind, pressed the barrel of his gun against her head, and with a single bullet, lacerated her midbrain. He then turned towards Razan, who was screaming for her life, and, execution-style, with a single bullet to the back of the head, killed her. On his way out, he shot Deah one last time -- a bullet in the mouth -- for a total of eight bullets: two lodged in the head, two in his chest and the rest in his extremities.

Deah, Yusor and Razan were executed in a place that was meant to be safe: their home. For months, this man had been harassing them: knocking on their door, brandishing his gun on a couple of occasions. His Facebook was cluttered with anti-religion posts. Yusor felt particularly threatened by him. As she was moving in, he told Yusor and her mom that he didn't like the way they looked. In response, Yusor's mom told her to be kind to her neighbor, that as he got to know them, he'd see them for who they were. I guess we've all become so numb to the hatred that we couldn't have ever imagined it turning into fatal violence.

The man who murdered my brother turned himself in to the police shortly after the murders, saying he killed three kids, execution-style, over a parking dispute. The police issued a premature public statement that morning, echoing his claims without bothering to question it or further investigate. It turns out there was no parking dispute. There was no argument. No violation. But the damage was already done. In a 24-hour media cycle, the words "parking dispute" had already become the go-to sound bite.

I sit on my brother's bed and remember his words, the words he gave me so freely and with so much love, "I am who I am because of you." That's what it takes for me to climb through my crippling grief and speak out. I cannot let my family's deaths be diminished to a segment that is barely discussed on local news. They were murdered by their neighbor because of their faith, because of a piece of cloth they chose to don on their heads, because they were visibly Muslim.

Some of the rage I felt at the time was that if roles were reversed, and an Arab, Muslim or Muslim-appearing person had killed three white American college students execution-style, in their home, what would we have called it? A terrorist attack. When white men commit acts of violence in the US, they're lone wolves, mentally ill or driven by a parking dispute. I know that I have to give my family voice, and I do the only thing I know how: I send a Facebook message to everyone I know in media.

A couple of hours later, in the midst of a chaotic house overflowing with friends and family, our neighbor Neal comes over, sits down next to my parents and asks, "What can I do?" Neal had over two decades of experience in journalism, but he makes it clear that he's not there in his capacity as journalist, but as a neighbor who wants to help. I ask him what he thinks we should do, given the bombardment of local media interview requests. He offers to set up a press conference at a local community center. Even now I don't have the words to thank him. "Just tell me when, and I'll have all the news channels present," he said.

He did for us what we could not do for ourselves in a moment of devastation. I delivered the press statement, still wearing scrubs from the previous night. And in under 24 hours from the murders, I'm on CNN being interviewed by Anderson Cooper. The following day, major newspapers -- including the New York Times, Chicago Tribune -- published stories about Deah, Yusor and Razan, allowing us to reclaim the narrative and call attention the mainstreaming of anti-Muslim hatred.

These days, it feels like Islamophobia is a socially acceptable form of bigotry. We just have to put up with it and smile. The nasty stares, the palpable fear when boarding a plane, the random pat downs at airports that happen 99 percent of the time.

It doesn't stop there. We have politicians reaping political and financial gains off our backs. Here in the US, we have presidential candidates like Donald Trump, casually calling to register American Muslims, and ban Muslim immigrants and refugees from entering this country. It is no coincidence that hate crimes rise in parallel with election cycles.

Just a couple months ago, Khalid Jabara, a Lebanese-American Christian, was murdered in Oklahoma by his neighbor -- a man who called him a "filthy Arab." This man was previously jailed for a mere 8 months, after attempting run over Khalid's mother with his car. Chances are you haven't heard Khalid's story, because it didn't make it to national news. The least we can do is call it what it is: a hate crime. The least we can do is talk about it, because violence and hatred doesn't just happen in a vacuum.

Not long after coming back to work, I'm the senior on rounds in the hospital, when one of my patients looks over at my colleague, gestures around her face and says, "San Bernardino," referencing a recent terrorist attack. Here I am having just lost three family members to Islamophobia, having been a vocal advocate within my program on how to deal with such microaggressions, and yet -- silence. I was disheartened. Humiliated.

Days later rounding on the same patient, she looks at me and says, "Your people are killing people in Los Angeles." I look around expectantly. Again: silence. I realize that yet again, I have to speak up for myself. I sit on her bed and gently ask her, "Have I ever done anything but treat you with respect and kindness? Have I done anything but give you compassionate care?" She looks down and realizes what she said was wrong, and in front of the entire team, she apologizes and says, "I should know better. I'm Mexican-American. I receive this kind of treatment all the time."

Many of us experience microaggressions on a daily basis. Odds are you may have experienced it, whether for your race, gender, sexuality or religious beliefs. We've all been in situations where we've witnessed something wrong and didn't speak up. Maybe we weren't equipped with the tools to respond in the moment. Maybe we weren't even aware of our own implicit biases. We can all agree that bigotry is unacceptable, but when we see it, we're silent, because it makes us uncomfortable.

But stepping right into that discomfort means you are also stepping into the ally zone. There may be over three million Muslims in America. That's still just one percent of the total population. Martin Luther King once said, "In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends."

So what made my neighbor Neal's allyship so profound? A couple of things. He was there as a neighbor who cared, but he was also bringing in his professional expertise and resources when the moment called for it. Others have done the same. Larycia Hawkins drew on her platform as the first tenured African-American professor at Wheaton College to wear a hijab in solidarity with Muslim women who face discrimination every day. As a result, she lost her job. Within a month, she joined the faculty at the University of Virginia, where she now works on pluralism, race, faith and culture.

Reddit cofounder, Alexis Ohanian, demonstrated that not all active allyship needs to be so serious. He stepped up to support a 15-year-old Muslim girl's mission to introduce a hijab emoji.

(Laughter)

It's a simple gesture, but it has a significant subconscious impact on normalizing and humanizing Muslims, including the community as a part of an "us" instead of an "other." The editor in chief of Women's Running magazine just put the first hijabi to ever be on the cover of a US fitness magazine. These are all very different examples of people who drew upon their platforms and resources in academia, tech and media, to actively express their allyship.

What resources and expertise do you bring to the table? Are you willing to step into your discomfort and speak up when you witness hateful bigotry? Will you be Neal?

Many neighbors appeared in this story. And you, in your respective communities, all have a Muslim neighbor, colleague or friend your child plays with at school. Reach out to them. Let them know you stand with them in solidarity. It may feel really small, but I promise you it makes a difference.

Nothing will ever bring back Deah, Yusor and Razan. But when we raise our collective voices, that is when we stop the hate.

Thank you.

(Applause)