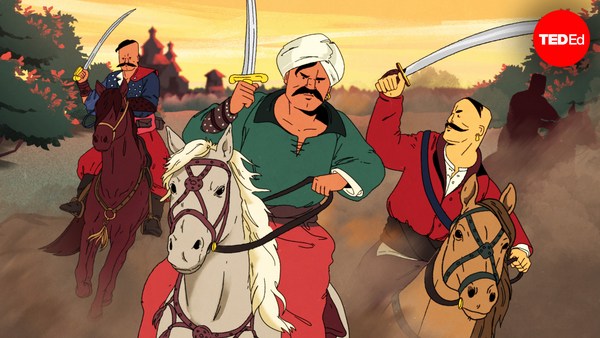

At dawn on July 29th, 1364, John Hawkwood— an English soldier turned contract mercenary— led a surprise attack against an army of sleeping Florentine mercenaries. The enemy commander quickly awoke and gathered his men to launch a counterattack. But as soon as the defending army was ready to fight, Hawkwood’s fighters simply turned and walked away. This wasn't an act of cowardice. These mercenaries, known as condottieri, had simply done just enough fighting to fulfill their contracts. And for Italy’s condottieri, war wasn’t about glory or conquest: it was purely about getting paid.

For much of the 14th and 15th centuries, the condottieri dominated Italian warfare, profiting from— and encouraging— the region’s intense political rivalries. The most powerful of these regions were ruled either by wealthy representatives of the Catholic Church or merchants who’d grown rich from international trade. These rulers competed for power and prestige by working to attract the most talented artists and thinkers to their courts, leading to a cultural explosion now known as the Italian Renaissance. But local rivalries also played out in military conflicts, fought almost entirely by the condottieri. Many of these elite mercenaries were veterans of the Hundred Years’ War, hailing from France and England. When that war reached a temporary truce in 1360, some soldiers began pillaging France in search of fortune. And the riches they found in Catholic churches drew their raiding parties to the center of the Church’s operations: Italy. But here, savvy ruling merchants saw these bandits’ arrival as a golden opportunity. By hiring the soldiers as mercenaries, they could control the violence and gain an experienced army without the cost of outfitting and training locals. The mercenaries liked this deal as well, as it offered regular income and the ability to play these rulers off each other for their own benefit.

Of course, these soldiers had to be kept on a tight leash. Rulers forced them to sign elaborate contracts, or condotta, a word that became synonymous with the mercenaries themselves. Divisions of payment, distribution of plunder, non-compete agreements— it was all spelled out clearly, making war merely another dimension of business. Contracts specified the number of men a commander would provide, and the resulting armies ranged from a few hundred to several thousand. Individual soldiers regularly moved between armies in search of higher payments. And when their contracts expired, condottieri commanders became free agents with no expectation of ongoing loyalty. When John Hawkwood launched his surprise attack against the Florentine condottieri, he was working for Pisa. Later, he would fight for Florence and many of Pisa’s other enemies.

But regardless of who was contracting them, the condottieri fought primarily for themselves. Their extensive military experience allowed them to avoid taking unnecessary risks in the heat of battle. And— while still deadly— their clashes rarely led to crushing victories or defeats. Condottieri commanders wanted battles to be inconclusive— after all, if they established peace, they’d put themselves out of business. So even when one side did win, enemy combatants were typically held hostage and released to fight another day. But there was nothing merciful about these decisions. Contracts could just as easily turn them into ruthless killers, as in 1377, when Hawkwood led the massacre of a famine-stricken town who’d tried to revolt against the local government.

Over time, foreign condottieri were increasingly replaced by native Italians. For young men from humble origins, war-for-profit offered an attractive alternative to farming or the church. And this new generation of condottieri leveraged their military power into political influence, in some cases even founding ruling dynasties. However, despite cornering the market on Italian warfare for nearly two centuries, the condottieri only truly excelled at engaging in just enough close-range combat to fulfill their contracts. Over time, they became outclassed by the gunpowder weaponry of France and Spain’s large standing armies, as well as the naval might of the Ottomans. By the mid 16th century, these state-sponsored militaries forced all of Europe into a new era of warfare, putting an end to the condottieri’s conniving war games.