Give me 30 seconds, and I can give you a list of 30 terrifying challenges facing humanity and the planet at this point in history. And we wouldn't sleep tonight. There are so many of them, and they seem so frightening; it's not really surprising that many of us are feeling a little bit disheartened and a little bit anxious at the moment. But the way I see it, there are really only two things stopping the world working at the moment. The first one is the fact that countries don't collaborate enough. We know the solutions to most of those challenges, but we don't implement them because we don't work together. And the second thing that's stopping the world working properly is the fact that every single one of those challenges has been caused by the behaviour of human beings. And if we can change that, we can change everything. Now, those sound like very big tasks, and they are, but I'm optimistic. For the last 10 years, I've been working on projects and plans and policies to try and attack those two barriers to making the world work better. Some of them, I try to encourage countries to implement, but the coolest ones, I keep, and I try to do them myself. So I'd like to tell you about two of those in the few minutes that I've got today. The first one is more of an update. It's a project called the Good Country Index, which I launched back in 2014. I haven't spoken about it for a while, but it's been through four different editions, and I thought it would be good to give an update. So the Good Country Index is an attempt to measure what every country on earth gives to the rest of the world outside of its own borders - a kind of balance sheet for the world, if you like. A lot of people when I originally launched it said, "Not another country index. There're enough of those around already." But the interesting thing is that almost all of the others look inwards. They treat countries as if they were little islands inhabiting their own private oceans. But surely that doesn't really make sense. Because everything everybody does has an impact on all of us, always. If one country pollutes the air or the water, that's our air and our water. If they go to war, it drags other countries in and the refugees pour out. There's really nothing you can do anymore that only impacts the domestic population. So what the Good Country Index attempts to do is to make a start towards helping people to understand that this is an interconnected system, by measuring what each country contributes to the rest of the world. Now, it's not my opinion which countries rank higher and which ones rank lower; it's formed from a set of 35 large databases which mostly come from the UN system, and what they do is they measure the positive and negative effects that countries have. It's always been a tiny bit controversial. But that's kind of good because it helps to start a new kind of argument. In fact, it works really well. Within hours of me releasing the first edition of the Good Country Index, I started receiving thousands and thousands of beautiful hate mails from trolls all over the world, demanding to know why the country they hate ranks so high, and the country they love ranks so low, and how I cooked up the entire thing just to produce that specific result and annoy them personally. (Laughter) So we have conversations about these things and we'd argue about it, and at the end I'd always say the same thing, "Look, it's working." I don't know if I'm right or if you're right, but in the end, we are discussing the right thing: we are talking about not how well is your country doing, but how much is your country doing. And that's what it was supposed to achieve. So by pushing the direction of the argument, the conversation, towards a new way of looking at countries, then I think that it's pushing the agenda forward. So, my colleague Robert Govers and I just released the latest edition of the Good Country Index. I'll just give you a very quick glimpse of what's going on there. Finland came first. One of these days, somebody is going to invent a country ranking that does not have a Nordic country in the top ten. (Laughter) An index of modesty perhaps? Anyway well done Finland, seriously! It's absolutely great. And another rather interesting thing happened in this latest edition of the Good Country Index, and that was what you can see if you go slightly lower in the Index, that the United States of America has for various reasons sunk quite a long way since the last edition, and Russia for various reasons has risen. And we now have this peculiar situation where the USA and Russia, relative to the size of their economies, are neck and neck, quite a long way down the Index. It's like two mean kids holding hands at the edge of the playground and refusing to join the others. (Laughter) (Cheering) (Applause) But hey, it's an interesting result, but in the end, I'm afraid to say that the world hasn't changed very much since the first one came out in 2014. It's still: America first, Britain first, Russia first, Germany first. And in a way, I understand that. I don't have a problem with it. I mean after all, if you are elected to run a country, it's pretty obvious that you put that country's interests first. But what I find rather demoralising about those kinds of sentiments is the implication that everybody else has to come last. And this is what I dispute. I think we can all come first. A nice thing about the job I've been doing for the last 20 years or so, advising governments around the world and trying out real policies in the real world, is that it's perfectly possible to harmonise your domestic and your international responsibilities. You can do the right thing for your own people, and you can do the right thing for humanity at the same time without sacrificing yourself. And the funny thing is it makes better policies. This is something that most governments have simply never tried. So, on to the second thing that's stopping the world working: the slightly more complicated issue of the behaviour of us humans. Well, to get started on this, I thought it'd be interesting to try to find out how many people in the world already agree with some of these basic principles, the ones outlined behind the Good Country Index. So Robert and I did some research, and we discovered that no less than 10% of the world's population appears to fully share the principles of the Good Country, the idea that countries should collaborate and cooperate a great deal more and compete a tiny bit less. This is great news. Ten percent, that's 760 million people. If that were a nation, that would be the third largest nation on the planet after China and India. And I have to admit that when those numbers came out, I got very excited. But then on mature reflection, I realised that, actually, the counterpart of that is that 90% of the people in the world don't agree with that proposition, and I think if one was going to take this challenge seriously, one has to focus on the 90%. It's not enough just to sell messages to the people who already agree with you and try to make them make tiny tweaks in their behaviour because frankly, it's too late for that. We are in too much of a hurry. We need big change, and we need it very soon. In fact, we need it right now. So how can we deeply educate the majority of the world's population to behave in a way which is more friendly to the world we live in and more friendly to each other? Because, by the way, when I was speaking of trolls, of course it reminded me of this strange idea that emerged recently, and I don't know where it came from, that the people who care more about local things and the people like me who care more about global things should be enemies. Who thought of this idea? This is the most dangerous idea in the world at the moment, and I think we should all look out for it and challenge it whenever we hear it. The people who care more about local things and the people who care more about global things shouldn't be enemies. They should be working together. We should be glad that each other exists. There isn't time for this kind of childish tribalism. We need to get on and fix things. Well anyway, as I was saying, the 90% need to be fundamentally educated in a different way. And I started looking at some of the websites of the NGOs and the campaigning organisations and the charities, and I began to notice there was a common theme emerging. There was a sentence, which in one form or another kept on cropping up. The sentence was something like this: "And we should leave the world in a better state for our children." And I've tried to read this sentence about 93 times in different places. I began thinking to myself, "You know, that's pretty arrogant really." The idea you could take something huge like climate change, a huge systemic problem or conflict or migration that's taken billions of people centuries to perpetrate, and you are going to fix it before you check out? (Laughter) It's this kind of arrogance and impatience that causes more problems than it solves. If we only have the nerve, if we only have the courage to give it one generation, we can fix everything and we can fix it for good. Because every single day that passes, humanity has an opportunity to start again. Because every single day that passes, new children are born, and they can learn in new ways. So there is a solution to every single challenge facing humanity; it's called education. But we need to do it in a new way and a different way and a much more ambitious way than we've done it before. Imagine if you will, a test tube rack of the sort you probably had when you studied science at school. And in this test tube rack made of wood, there are 7, 8, 10, I don't know, little glass test tubes, and each one contains a different coloured liquid. And each one of those liquids is a vaccine, an educational vaccine against the behaviours that cause climate change, conflicts, human right abuses, terrorism, migration, pandemics and all the rest of it. And if we administer these educational vaccines to all of our children, in the next generation, they will be incapable of continuing the behaviours that we have indulged in for so long. If we teach our children cultural anthropology at the age of six - it's a wonderful subject for six-year-olds - they'd grow up taking a scientific pride in understanding cultural differences. They are immunised against the kind of ignorance that leads to prejudice and intolerance. I know that one works because I experimented it on my children, and it works a charm. (Laughter) If we want to lessen the speed of climate change, we need to teach our children oceanography and meteorology, and then maybe one day they'll switch off the damn light when they leave bedroom. (Laugher) We need to teach our children hygiene so that there is less disease. We need to teach them to meditate so there is less mental illness and they learn to have more empathy and understanding and kindness towards everybody else. There are so many subjects. I can't decide which ones they should be. What I think we need to do is to have a big global discussion on the internet, where everybody puts in their own idea about what should be the next set of values that we're going to teach the next generation of children so they can run towards the global challenges instead of running away from them as we've done. And we can do this. Next year, it will be my aim, my ambition, to have one hundred ministers of education signing up to this new global compact of educational values. UNESCO has already signed a letter saying they would like to support this if we can get it going. And if you have any doubts about whether it's possible for humanity to engage in such a big common project despite all of our cultural differences, well, just have a think about the United Nations' charter or the human rights documentation. Have a read if you haven't read it for a while. These are the most beautiful documents ever produced by humanity, and they really give you faith because they remind you as you read them that we are capable of behaving like a single species inhabiting a single planet. We can do it if we really want to and if we do it at scale. The good news is it's more about joining up the dots than starting from scratch. Because there're hundreds and hundreds if not thousands of projects around the world at the moment, finding and experimenting different ways of educating children so they behave better in the future. The trouble is they're mostly single topics and in single countries. There's no time for doing it slowly now. We need to do it big, and we need to do it in one go. Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate activist, is beginning to discover and beginning to show us how very difficult it is to persuade grown-ups to change their behaviour. But the simple fact of the matter is that we can see that a lot of children have got the right attitude, but they don't have the solutions. Some adults have the solutions, but they definitely don't have the right attitude. And so, guess what, it's another necessity for collaboration - the children and the grown-ups working together. We all have to think very hard now about being better human beings. And that's about being better citizens, both locally and globally, but it's also, perhaps mainly, about being better ancestors. If we can do that, we can make the world work. Thank you. (Applause) (Cheering)

Related talks

Simon Anholt: Which country does the most good for the world?

Nic Marks: The Happy Planet Index

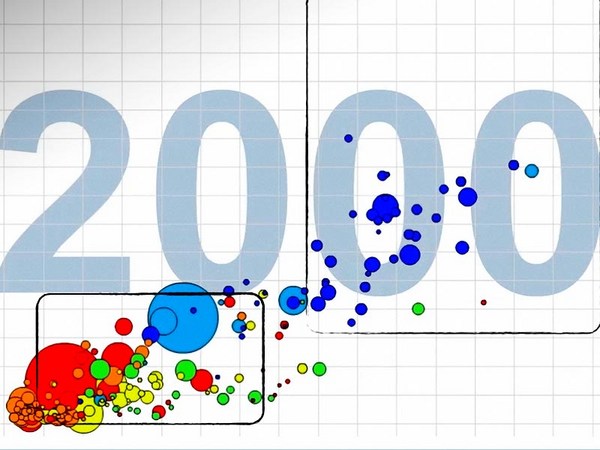

Hans Rosling: New insights on poverty

Hans Rosling: Let my dataset change your mindset

Jamie Drummond: Let's crowdsource the world's goals