So I'm an evolutionary biologist. The thing I love most about evolution is the story. Evolution is a single story that links every species, every branch in the tree of life together. It's this sense of connectivity with the rest of the living world. It's like one of the reasons why I became a biologist in the first place.

Now, when Charles Darwin, my man Chuck D, when he first proposed this theory ...

(Laughter)

When he first proposed the theory of evolution, he imagined it as this slow, gradual process that played out over thousands or millions of years. But now, in the face of all the different changes that we are making to the planet, we're finding that evolution is rapidly altering species around our planet in order to live alongside us. And in our short time on this planet, we have trimmed, trained and reshuffled the tree of life at breakneck speed. 10,000 years ago, we had already learned how to manipulate the basic building blocks of life, turning wild plants and animals into domesticated forms to use for our own purposes. With mass global transportation, we've reshuffled species around the globe, bringing them together and forming all new ecological interactions. And on top of that, we've fundamentally altered Earth's surface and its climate through industrialized agriculture, urbanization, pollution and global warming.

Now I've dedicated my life to trying to understand the lasting biological impacts of our human footprint. One of the things that I've learned along the way is that life is a paradox. It's simultaneously incredibly fragile and relentlessly resilient. The thing that impresses me most is that despite our devastating impacts on this planet, I'm constantly in awe of the surprising, incredible, amazing ways that life is changing, evolving and adapting to a time that's literally defined by our species' impact on the planet. We now live in a time where one half of the human species lives in cities. As urban areas grow and expand, life around the world, non-human life, is changing to figure out how to exploit the novel resources and avoid the potential dangers.

My research group and my colleagues have been studying these small lizards called anoles that occur across the island of Puerto Rico. Now, most of the time, these lizards spend their time running up and down trees, chasing after insects, doing the things you know, that lizards do. But in cities, they have evolved at the genetic level. They've evolved longer limbs and larger sticky toe pads to utilize the sides of buildings and artificial surfaces like glass and metal and concrete as their homes. They've also evolved greater heat tolerance to deal with the high temperatures that define dense urban environments, what we call urban heat islands. And what's more, is that multiple populations of this species have come up with the same solutions over and over again, independently. Showing us that not only is the process of evolution very rapid sometimes, but in some cases it can also be quite predictable.

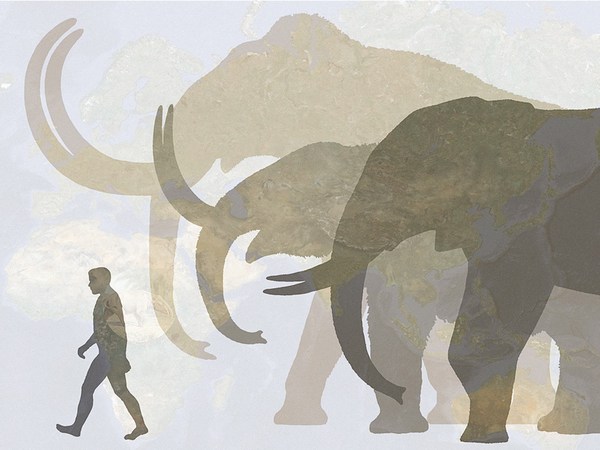

Now, urbanization is not our only impact on this planet, far from it. Perhaps our earliest and longest-lasting impact has been through our want and need to hunt other species for food and for sport.

I spent the last few years studying the evolution of African elephants in response to ivory poaching. In Mozambique, there was a civil war from 1977 to 1992. During this time, in Gorongosa National Park, elephants in particular were reduced by 90 percent because of the ivory trade, being targeted for their trademark tusks. Now, under most circumstances, African elephants have tusks, all males have tusks, the vast majority of females have tusks. But there is a small number of females that carry a gene that prevents them from growing their tusks. But after the Mozambican Civil War, one-half of the surviving females, completely tuskless. Now, during a time where individuals are being hunted specifically for a trait, having tusks, not having that trait puts you at a decided advantage in your ability to survive. That in and of itself is natural selection. Those surviving females then went on and passed that gene on to many of their daughters. That turnover of genes across generations, that is rapid evolution in this long-lived species in response to a decade and a half of human hunting.

I remember going to Gorongosa for the first time and participating in these elephant captures where we collar these individuals and collect data and track their movements. And we came across this female, and she's old enough where we know that she had survived the Mozambican Civil War. Now we sedated this female and as we were there, sort of working up all of these data, looking into her big, groggy, sleepy eyes, and it really struck me, the impact that our species can have on the rest of the living world. This female, she lived during a time that saw nine out of ten of the members of her species slaughtered. But she survived. She grew up, she went on and had children, had grandchildren, became the matriarch of a family group. But what strikes me the most about this story is that the reason for all of that destruction and that slaughter was simply because humans like to make trinkets out of their teeth. Which is about the most ridiculous and sad thing I've ever had to say out loud. But we live in a time where even the simplest human whims can fundamentally alter the evolutionary fate of the largest land animal on our planet.

And many of these stories of rapid evolution are sad, but some also offer us hope for our own future on this planet. In nature's struggle to deal with all the nonsense that we're throwing at her in all these different ways, some of those solutions may lead us to novel insights that may help our bodies deal with things that we currently struggle with that will allow us to survive all the different changes that we're making on this planet.

For instance, fast forward to the year 2040, it's estimated that there will be about 30.2 million new cancer cases diagnosed in that year alone. Now, we know a lot about the genes and mutations that are responsible for many cancers or make an individual more predisposed to getting cancer. We know a lot less about potential genetic mutations or variation that may make an individual more resistant or more resilient to cancer. But perhaps nature has already found the solution.

April 26th, 1986, the day before my very first birthday. There was an explosion in the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Humans were immediately evacuated from that region, what is now called the Chernobyl exclusion zone. But in the decades since, wildlife has actually moved into the Chernobyl exclusion zone and has proliferated. So my research group and colleagues, we have been studying the wolves that live in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, trying to understand how they have responded biologically to now generations of exposure to elevated radiation levels. Now, if we consider a wolf pup that's born in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, it lives every single day of its life, from the time it's born, gaining increased doses of exposure from its environment. With every meal that that animal eats, it then gets another dose of radiation from prey species. And we can see that radiation accumulating in this wolf population in the form of cesium-137. And one of the things that our data are showing us is that the fastest-changing regions of the Chernobyl wolf genome occur in and around genes that we know are involved in cancer or in the mammalian anti-tumor immune response. We're now working with biomedical companies and cancer biologists to understand the physiological impacts of these mutations with the hope that at least some of these changes may lead us to novel therapeutics that might result in new treatments for cancer in humans.

In this grand story of life, we're writing a brand new chapter. Now our chapter in this story is not a pretty one, let's be honest. As a matter of fact, there's a distinct possibility that our species could bring about Earth's sixth major mass extinction event. So, you know, that sucks.

(Laughter)

It'd be messed up if I had just left the talk like that, I was like, "Hope you're all proud of yourselves, bye."

(Laughter)

(Applause)

But luckily I don't have to leave the talk like that because this chapter is still being written. Our chapter in this story of life is still happening, which means that there are still many possibilities ahead of us. We have the possibility to act, the possibility to fight for those species that don't have the ability to fight for themselves. We have the possibility to turn our chapter in this story into one of redemption, one of hope and one of care for this epic legacy of life on this planet that we've inherited. A legacy, by the way, that's four billion years in the making. Which brings up the possibility that we can pass on a world to our kids and our grandkids so that they can enjoy and revel in the incredible biodiversity that the story of evolution has produced. What Charles Darwin referred to as “endless forms most beautiful.”

One way or another, what we do matters. We live in a time when we are literally etching our decisions into the DNA of the species that live in, on and around us. When we're considering this story that we're writing, what do we want our chapter in this grand story of life to be?

Thank you.

(Applause)