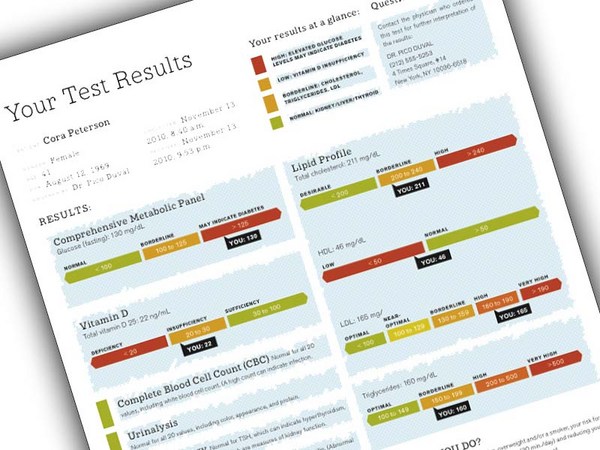

The story I want to tell you about, started to me, in 1996 when I was studying in England. One day, I was glancing through my bank statement (I didn't have much to look at) and I've noticed that in the upper corner there was a symbol, that I'm going to show you, saying that document had been made in plain language, for me to understand it. The idea interested me; I tried to find out what that was and I found out that there was a campaign for the simplification of language, which was the "Plain English Campaign". I thought it was a fabulous idea, for about one day or two, and I've never thought about it since. When I came back to Portugal, for good, I came across with several documents - for example, my work contract, the papers I had to sign to buy a house, the electricity bill -- a series of documents that reminded me of that bank statement. Not because they were equally clear and simple, but because they were the exact opposite. Because I had to read everything twice or thrice, to begin to understand what was written there. And then, that little seed that had been sown in 1996, started germinating. And one day, I found myself entering through my boss' office and quitting my job to dedicate myself to this. And so, what did I find out, right off the start? I found out that it was a much more severe problem than I thought. It wasn't only about these documents being complex and annoying, it was the fact that Portuguese people's literacy -- literacy is the hability to understand written documents -- is extremely low. I'm going to show you a chart about Portuguese people's literacy [rate]. You know that about 10, 11% of people, in Portugal,

don't know how to read nor write at all, yet. Over there are those who know, or say they know, how to read and write. So, what do we have? We have that group of red people in level 1, which is the lowest in literacy [rate]. They are persons who are able to join letters, but they can't, actually, understand. For example, if a person, from that red group, has to pick up the package leaflet of a medicinal product, to give a dose of medicine to his/her child, he/she can't, can't understand the information. 50% of the Portuguese. Then we have 30% more, those yellow ones, over there, people who get by on the daily basis. That is, if they don't have to read anything too new or too different, they will manage. But, for example, if they work in a factory and a new machine arrives and they have to read the machine's manual to be able to work with it, they can't do it anymore. And there they go, 80% of the Portuguese people. Then we have a few more that can handle documents, as long as they are not too complex, and we have 5% of the population that can handle really complex documents. Now, just so you don't think this is normal, that over there is Sweden. While we have 20% of people with the literacy considered essential for a daily basis, Sweden has 75%. And looking at that, what did I realize? I realized we live in an apartheid of information. I realized that there's a small minority of people who has indeed access to information and can use it to their advantage and a huge majority that can't. And because they can't, they are excluded and they are impaired. Let me give you an example. That one is Mr. Domingos, my building's doorkeeper. Mr. Domingos started to read at the age of 27, so, he falls in that yellow group that we have seen a little while ago. From time to time, I'm arriving home and he says: "Miss Sandra!"; "Yes, Mr. Domingos." "Here is a little letter." So, the deal is: when Mr. Domingos or someone in the family or in the neighbourhood receives something that they don't understand, they come to me and I help them to translate it. And so, that time he said to me like this: "Oh, Miss Sandra, I'm about to throw this away, but check it if this is important." It was very important. He had been waiting, for quite a while, to have a knee surgery and that was the letter of the famous surgery-bank checks. When a person is waiting for a long time, they get a bank check and with that bank check they can have that surgery in the private sector. It was almost thrown away into the garbage, Mr. Domingos' letter. In that same year, I've found out, only 20% of people had used these surgery-bank checks. The other 80%, I don't believe they had been cured while they were waiting. They most likely did the same as Mr. Domingos: "Ah! What's this? I'm not understanding, it's going to the garbage". They lost the opportunity to have the surgery they needed. What happens here? When people don't understand this has severe consequences -- to the individual, but also for the country. When I don't understand which are my rights, the benefits I can have access to, I can't understand my duties and I'm not an active and participative citizen either. Now, maybe, you are sitting there and thinking: "Yeah, poor Mr. Domingos... Bad luck, isn't it? Me?! I'm in the green ones." "I'm absolutely sure that I'm one of the green ones. I was selected to come to TED! Hum?" (Laughter) So the deal is: I have here some texts to read to you and I'm going to see what color are you when I finish reading. So, come on, this is an automobile insurance contract. It says this: "Unless contrary stipulation, the decease of the ensured person, the ensured capital is provided, in case of predeceasing of the beneficiary relatively to the ensured person, to the heirs of the last, in case of the simultaneous decease of the ensured person and of the beneficiary, to the heirs of the last". Hum? (Laughter) Next, there's another one, from the medicines' package leaflet, that says the following: "Warning! It may also occur erythema, edema, vesiculation, keratolysis and urticaria." Hum? Are you clear? And this one is really good. This one, I signed a renting contract to the new office on Friday and I laughed my head off. So, it said: "I, as a cosigner, assume the opportune payment of the rents, waiving the benefits of the division and prior foreclosure." When I heard "opportune payment" ["storm payment" in Portuguese], I imagined myself bursting in there, slamming the door and saying: "Here's the money!!!" (Laughter) But it's not! (Laughter) (Applause) But it's not! (Applause) (Applause) (Applause) So, it's this: when we leave our area of expertise -- and it only takes a little; there is no need to go to the string theory or something like that, it only takes a little... (Laughter) What happens? We get as lost as Mr. Domingos. And these documents are not written by experts to experts, as the ones from the string theory. No! These are documents written for me, these are the public documents, the public documents I need to understand in my daily life, to govern myself, to live my life. These are the renting contracts, the package leaflet of the medicines. It's all this. The electricity bills. This has to be clear, so that I can understand. Because, if I can't understand, what happens? I make mistakes, I get wrong. I'm going to give you an example of mistakes that were committed, bad decisions made for not being able to understand documents. Do you remember the subprime crisis that took place in the United States? What happened? People signed those loans to buy houses, without truly understanding what they were signing. Because if they knew what they were signing, they'd know that as soon as the interest rate started to rise, the monthly payment would also increase, they wouldn't be able to pay anymore and they would end up without a house. So, the rest, after that, next, everything crumbled down and we know the rest. Do you think that if there was a culture of clarity in the financial sector things would have got up to where they've got? I don't think so. So, how do you solve this problem, this such big difference between the literacy [rate] of the Portuguese, that is down here, and the complexity of the public documents, those ones we need to understand in our daily lives, sorry, that are up here? So, the first think that comes to mind is, "If literacy is down here, let's make it rise" -- isn't it? Let's educate people. Let's, let's... of course we will, of course we will educate people. The thing is, it's hard and it's slow. And I don't even want to imagine how many generations it will take until we are at Sweden's level. But, besides that, it's not only because it is slow. There is another problem. If the language of the documents isn't simpler, we've already seen that people, even with a high literacy level, like you, if the language is hard, they don't get cleared, they continue to be unable to understand these documents. So, besides increasing literacy [rate], and for now, it's much more important to reduce the complexity of documents and simplify the language. I'm going to show you an example. When I talk about simplifying the language. Notice! On the left side of a contract: "It is agreed that the insurance company, bla bla bla, bla bla bla, bla bla..." This is a before and after example. What do we mean with simplifying language? It's communicating in a simple and clear way, enabling our reader to understand it at first glance. What do you prefer? Before or after? There isn't much doubt, is there? So, how is this achieved? How can you make the State and companies communicate with citizens in a language they can understand at first glance? There are several ways. There are countries that are going by the path of legislation. For example, Sweden and the United States introduced, last year, a legislation that forces the State to communicate with people in a language they can understand. And you think, "Well, that's normal. They are countries that are a bit ahead. "Sweden, maybe, much more than the United States. "But they are countries that are a bit ahead. "It would be nice if in our country there was also legislation towards that, wouldn't it be?" So it would. And there is! Since 1999. The Law of the Administrative Modernization says that the communication between the State and the people should be simple, clear, concise, meaningful, without acronyms, bla bla bla... But the thing is: it is not applied. So, the question, the path of going through legislation, enforcing through legislation, works in those countries where laws are made to be applied. Now, there is another way, the way of marketing. How does that work? It's like this: private companies change their language; communicate in a clearer and simpler way, they make a big fuss about it, consumers love it, the sales rise, it works beautifully. But it works for the private sector. Now, what is the third path, and to me, the most important one? It's the path of civil movements, that are based in a mentality shift. In countries where this really went forward -- do you remember the English label, of the "Plain English Campaign"? -- this is all based on a consumers' movement. So, what does it take for that civic movement to happen? We need to understand two very important things: First, wanting to understand these public documents is not a whim, is not an intellectual curiosity. It is a necessity that I have in my daily life. And above all, it is a right, it is everyone's right. On this side we have: understanding is a right. And we have to understand another thing too, which is: he who writes, has to write in order to be understood. How do we get there? First of all: we have to become demanding consumers and citizens. Think it this way: next time someone gives you a document that you just simply don't understand, don't be shy, don't keep quiet, pretending that you are understanding everything. No! Demand to understand. Ask. I know that this is not easy. Turn to the gentleman in the little suite and say: "Look here, this contract, this part, what does this mean?" It's not easy, and perhaps it's even a bit embarrassing, isn't it? But it is not. It's a sign of intelligence. What do you teach your children when they have doubts in school? "Don't say nothing to anyone, shut up really good and act smart." No, you don't, right? You say: "Look, when you don't understand, you put your hand up in the air and ask the teacher until you are cleared." And that is exactly what we have to do, as consumers and citizens. So, next time you come across with a document you don't understand, demand to understand, put aside your pride and ask until you get completely cleared. Then, there's the other side, which is: "Okay, these awful documents "which are in circulation, they don't grow on trees. "Someone wrote them." Hum? Maybe, among this big group, some persons... I don't know, some lawyers, some public employees -- I'm not asking you to identify yourselves, but I ask you to search your own conscience. How many times do you write documents for the general public, for people that don't share your language, and you write them in a language that only you will understand? And you'll say: "Ah, that's because there is a reason, here!" Dear friends, I already heard all the reasons. There are thousands of reasons. They go like these: "Ah, it's the house's culture"; "Oh, my boss!" "Oh, the judge! And what if this goes to court?" "What you want is to destroy language. We have to educate people." "We can't lower the level"; bla, bla, bla... I've seen all of this. These are excuses. A while ago, they told us about Einstein. Einstein said this: "If you can't write about a subject, in a simple way, it's because, in fact, you don't understand it." So, if you... (Applause) To Einstein... (Applause) To Einstein...(Applause) So -- ah, ah, I don't have time! -- so, if you do know what you want to say -- don't you? -- you are aware of what you want to say, you just have to do one thing: believe that it is possible to write in a simple way. And how do you do that? It's very easy. You write to your grandmother. Hum? You write to your grandmother. I'm going to show grandma to you. (Laughter) You write with respect and without paternalism. And you use three techniques that I'm going to teach you. First of all: Start by the most important. Grandma has a lot to do. She is not going to read three pages to get to the main idea. Start by the most important. Next, use short sentences, because grandma, like anyone of us, if you make very long sentences, she gets to the end and she can't remember what you said in the beginning, anymore. And lastly, the third, use plain words, those ones that grandma knows. Alright? It's easy! Before I leave, I would like to talk to you about "Clara" (Clear). "Clara" is a project of social responsibility. It has this mission: to change the way how public communication is made. What do we do? We are going to launch this year a collection of "Claro" guides, that is, we are going to pick very, very, very complex subjects and put them simple. We are going to start with the "Claro" Guide of Justice. I think it is an area... that comes in handy. (Applause) And now I'm going to follow Manuel [Forjaz]'s advise. If it's time to ask, whoever wants to sponsor the "Claro" Guide of Justice -- I don't know... for example, the EDP Foundation, or...ha? -- come talk to me later. Another thing we will do is to grant prizes to the worse and best documents, because, indeed, there are people who are working to communicate in a clearer way, and that have to be rewarded, and there are lazy people that do nothing about it and need to be humiliated. So, we'll give prizes to the worst and to the best. I'm counting on your help. (Applause) (Applause) We are going to launch... we are going to launch the campaign via Clara's Facebook, so, send your friendship request and you'll be up to date. But, lastly, above all, what does "Clara" want? It wants to put two little things in your heads. The first one: demand to understand. Don't be shy. And write in order to be understood. Write to your grandma. And if you don't have a grandmother, write to Mr. Domingos, he will like it. Thank you. (Applause)