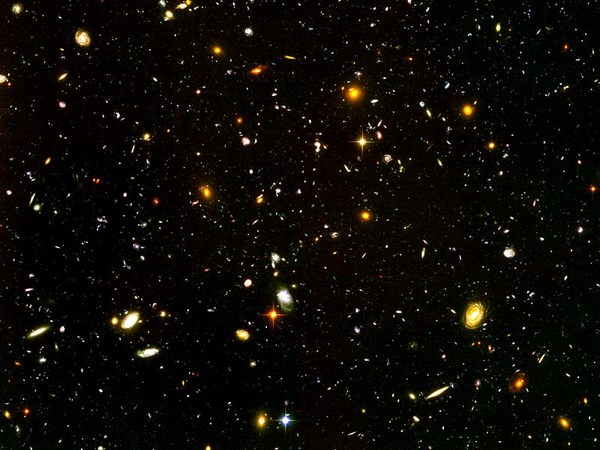

The universe began its cosmic life in a big bang nearly fourteen billion years ago, and has been expanding ever since. But what is it expanding into? That's a complicated question. Here's why: Einstein's equations of general relativity describe space and time as a kind of inter-connected fabric for the universe. This means that what we know of as space and time exist only as part of the universe and not beyond it. Now, when everyday objects expand, they move out into more space. But if there is no such thing as space to expand into, what does expanding even mean? In 1929 Edwin Hubble's astronomy observations gave us a definitive answer. His survey of the night sky found all faraway galaxies recede, or move away, from the Earth. Moreover, the further the galaxy, the faster it recedes. How can we interpret this? Consider a loaf of raisin bread rising in the oven. The batter rises by the same amount in between each and every raisin. If we think of raisins as a stand-in for galaxies, and batter as the space between them, we can imagine that the stretching or expansion of intergalactic space will make the galaxies recede from each other, and for any galaxy, its faraway neighbors will recede a larger distance than the nearby ones in the same amount of time. Sure enough, the equations of general relativity predict a cosmic tug-of-war between gravity and expansion. It's only in the dark void between galaxies where expansion wins out, and space stretches. So there's our answer. The universe is expanding unto itself. That said, cosmologists are pushing the limits of mathematical models to speculate on what, if anything, exists beyond our spacetime. These aren't wild guesses, but hypotheses that tackle kinks in the scientific theory of the Big Bang. The Big Bang predicts matter to be distributed evenly across the universe, as a sparse gas --but then, how did galaxies and stars come to be? The inflationary model describes a brief era of incredibly rapid expansion that relates quantum fluctuations in the energy of the early universe, to the formation of clumps of gas that eventually led to galaxies. If we accept this paradigm, it may also imply our universe represents one region in a greater cosmic reality that undergoes endless, eternal inflation. We know nothing of this speculative inflating reality, save for the mathematical prediction that its endless expansion may be driven by an unstable quantum energy state. In many local regions, however, the energy may settle by random chance into a stable state, stopping inflation and forming bubble universes. Each bubble universe —ours being one of them —would be described by its own Big Bang and laws of physics. Our universe would be part of a greater multiverse, in which the fantastic rate of eternal inflation makes it impossible for us to encounter a neighbor universe. The Big Bang also predicts that in the early, hot universe, our fundamental forces may unify into one super-force. Mathematical string theories suggest descriptions of this unification, in addition to a fundamental structure for sub-atomic quarks and electrons. In these proposed models, vibrating strings are the building blocks of the universe. Competing models for strings have now been consolidated into a unified description, and suggest these structures may interact with massive, higher dimensional surfaces called branes. Our universe may be contained within one such brane, floating in an unknown higher dimensional place, playfully named “the bulk,” or hyperspace. Other branes—containing other types of universes—may co-exist in hyperspace, and neighboring branes may even share certain fundamental forces like gravity. Both eternal inflation and branes describe a multiverse, but while universes in eternal inflation are isolated, brane universes could bump into each other. An echo of such a collision may appear in the cosmic microwave background —a soup of radiation throughout our universe, that’s a relic from an early Big Bang era. So far, though, we’ve found no such cosmic echo. Some suspect these differing multiverse hypotheses may eventually coalesce into a common description, or be replaced by something else. As it stands now, they’re speculative explorations of mathematical models. While these models are inspired and guided by many scientific experiments, there are very few objective experiments to directly test them, yet. Until the next Edwin Hubble comes along, scientists will likely be left to argue about the elegance of their competing models… and continue to dream about what, if anything, lies beyond our universe.

Related talks

Venus Keus: Three ways the universe could end

David Lunney: The life cycle of a neutron star

Fabio Pacucci: Could the Earth be swallowed by a black hole?

Stephen Hawking: Questioning the universe

Sean Carroll: Distant time and the hint of a multiverse