I want you to put off your preconceptions, your preconceived fears and thoughts about reptiles. Because that is the only way I'm going to get my story across to you. And by the way, if I come across as a sort of rabid, hippie conservationist, it's purely a figment of your imagination. (Laughter)

Okay. We are actually the first species on Earth to be so prolific to actually threaten our own survival. And I know we've all seen images enough to make us numb, of the tragedies that we're perpetrating on the planet. We're kind of like greedy kids, using it all up, aren't we? And today is a time for me to talk to you about water. It's not only because we like to drink lots of it, and its marvelous derivatives, beer, wine, etc. And, of course, watch it fall from the sky and flow in our wonderful rivers, but for several other reasons as well.

When I was a kid, growing up in New York, I was smitten by snakes, the same way most kids are smitten by tops, marbles, cars, trains, cricket balls. And my mother, brave lady, was partly to blame, taking me to the New York Natural History Museum, buying me books on snakes, and then starting this infamous career of mine, which has culminated in of course, arriving in India 60 years ago, brought by my mother, Doris Norden, and my stepfather, Rama Chattopadhyaya.

It's been a roller coaster ride. Two animals, two iconic reptiles really captivated me very early on. One of them was the remarkable gharial. This crocodile, which grows to almost 20 feet long in the northern rivers, and this charismatic snake, the king cobra. What my purpose of the talk today really is, is to sort of indelibly scar your minds with these charismatic and majestic creatures. Because this is what you will take away from here, a reconnection with nature, I hope.

The king cobra is quite remarkable for several reasons. What you're seeing here is very recently shot images in a forest nearby here, of a female king cobra making her nest. Here is a limbless animal, capable of gathering a huge mound of leaves, and then laying her eggs inside, to withstand 5 to 10 [meters of rainfall], in order that the eggs can incubate over the next 90 days, and hatch into little baby king cobras. So, she protects her eggs, and after three months, the babies finally do hatch out. A majority of them will die, of course. There is very high mortality in little baby reptiles who are just 10 to 12 inches long.

My first experience with king cobras was in '72 at a magical place called Agumbe, in Karnataka, this state. And it is a marvelous rain forest. This first encounter was kind of like the Maasai boy who kills the lion to become a warrior. It really changed my life totally. And it brought me straight into the conservation fray. I ended up starting this research and education station in Agumbe, which you are all of course invited to visit.

This is basically a base wherein we are trying to gather and learn virtually everything about the biodiversity of this incredibly complex forest system, and try to hang on to what's there, make sure the water sources are protected and kept clean, and of course, having a good time too. You can almost hear the drums throbbing back in that little cottage where we stay when we're there. It was very important for us to get through to the people. And through the children is usually the way to go. They are fascinated with snakes. They haven't got that steely thing that you end up either fearing or hating or despising or loathing them in some way. They are interested. And it really works to start with them. This gives you an idea of the size of some of these snakes.

This is an average size king cobra, about 12 feet long. And it actually crawled into somebody's bathroom, and was hanging around there for two or three days. The people of this part of India worship the king cobra. And they didn't kill it. They called us to catch it. Now we've caught more than 100 king cobras over the last three years, and relocated them in nearby forests.

But in order to find out the real secrets of these creatures [it was necessary] for us to actually insert a small radio transmitter inside [each] snake. Now we are able to follow them and find out their secrets, where the babies go after they hatch, and remarkable things like this you're about to see. This was just a few days ago in Agumbe. I had the pleasure of being close to this large king cobra who had caught a venomous pit viper. And it does it in such a way that it doesn't get bitten itself. And king cobras feed only on snakes. This [little snake] was kind of a tid-bit for it, what we'd call a "vadai" or a donut or something like that. (Laughter)

Usually they eat something a bit larger. In this case a rather strange and inexplicable activity happened over the last breeding season, wherein a large male king cobra actually grabbed a female king cobra, didn't mate with it, actually killed it and swallowed it. We're still trying to explain and come to terms with what is the evolutionary advantage of this.

But they do also a lot of other remarkable things. This is again, something [we were able to see] by virtue of the fact that we had a radio transmitter in one of the snakes. This male snake, 12 feet long, met another male king cobra. And they did this incredible ritual combat dance. It's very much like the rutting of mammals, including humans, you know, sorting out our differences, but gentler, no biting allowed. It's just a wresting match, but a remarkable activity.

Now, what are we doing with all this information? What's the point of all this? Well, the king cobra is literally a keystone species in these rainforests. And our job is to convince the authorities that these forests have to be protected. And this is one of the ways we do it, by learning as much as we can about something so remarkable and so iconic in the rainforests there, in order to help protect trees, animals and of course the water sources.

You've all heard, perhaps, of Project Tiger which started back in the early '70s, which was, in fact, a very dynamic time for conservation. We were piloted, I could say, by a highly autocratic stateswoman, but who also had an incredible passion for environment. And this is the time when Project Tiger emerged. And, just like Project Tiger, our activities with the king cobra is to look at a species of animal so that we protect its habitat and everything within it. So, the tiger is the icon. And now the king cobra is a new one.

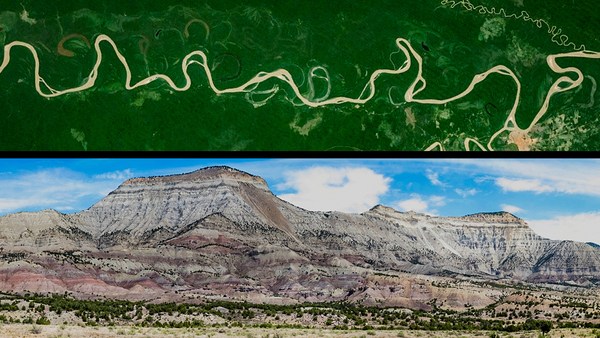

All the major rivers in south India are sourced in the Western Ghats, the chain of hills running along the west coast of India. It pours out millions of gallons every hour, and supplies drinking water to at least 300 million people, and washes many, many babies, and of course feeds many, many animals, both domestic and wild, produces thousands of tons of rice.

And what do we do? How do we respond to this? Well, basically, we dam it, we pollute it, we pour in pesticides, weedicides, fungicides. You drink it in peril of your life. And the thing is, it's not just big industry. It's not misguided river engineers who are doing all this; it's us. It seems that our citizens find the best way to dispose of garbage are in water sources. Okay. Now we're going north, very far north.

North central India, the Chambal River is where we have our base. This is the home of the gharial, this incredible crocodile. It is an animal which has been on the Earth for just about 100 million years. It survived even during the time that the dinosaurs died off. It has remarkable features. Even though it grows to 20 feet long, since it eats only fish it's not dangerous to human beings. It does have big teeth, however, and it's kind of hard to convince people if an animal has big teeth, that it's a harmless creature.

But we, actually, back in the early '70s, did surveys, and found that gharial were extremely rare. In fact, if you see the map, the range of their original habitat was all the way from the Indus in Pakistan to the Irrawaddy in Burma. And now it's just limited to a couple of spots in Nepal and India. So, in fact at this point there are only 200 breeding gharial left in the wild. So, starting in the mid-'70s when conservation was at the fore, we were actually able to start projects which were basically government supported to collect eggs from the wild from the few remaining nests and release 5,000 baby gharial back to the wild. And pretty soon we were seeing sights like this. I mean, just incredible to see bunches of gharial basking on the river again.

But complacency does have a tendency to breed contempt. And, sure enough, with all the other pressures on the river, like sand mining, for example, very, very heavy cultivation all the way down to the river's edge, not allowing the animals to breed anymore, we're looking at even more problems building up for the gharial, despite the early good intentions. Their nests hatching along the riverside producing hundreds of hatchlings. It's just an amazing sight. This was actually just taken last year. But then the monsoon arrives, and unfortunately downriver there is always a dam or there is always a barrage, and, shoop, they get washed down to their doom.

Luckily there is still a lot of interest. My pals in the Crocodile Specialist Group of the IUCN, the [Madras Crocodile Bank], an NGO, the World Wildlife Fund, the Wildlife Institute of India, State Forest Departments, and the Ministry of Environment, we all work together on stuff. But it's possibly, and definitely not enough. For example, in the winter of 2007 and 2008, there was this incredible die-off of gharial, in the Chambal River. Suddenly dozens of gharial appearing on the river, dead. Why? How could it happen?

This is a relatively clean river. The Chambal, if you look at it, has clear water. People scoop water out of the Chambal and drink it, something you wouldn't do in most north Indian rivers. So, in order to try to find out the answer to this, we got veterinarians from all over the world working with Indian vets to try to figure out what was happening. I was there for a lot of the necropsies on the riverside. And we actually looked through all their organs and tried to figure out what was going on. And it came down to something called gout, which, as a result of kidney breakdown is actually uric acid crystals throughout the body, and worse in the joints, which made the gharial unable to swim. And it's a horribly painful death.

Just downriver from the Chambal is the filthy Yamuna river, the sacred Yamuna river. And I hate to be so ironic and sarcastic about it but it's the truth. It's just one of the filthiest cesspools you can imagine. It flows down through Delhi, Mathura, Agra, and gets just about every bit of effluent you can imagine. So, it seemed that the toxin that was killing the gharial was something in the food chain, something in the fish they were eating. And, you know, once a toxin is in the food chain everything is affected, including us.

Because these rivers are the lifeblood of people all along their course. In order to try to answer some of these questions, we again turn to technology, to biological technology, in this case, again, telemetry, putting radios on 10 gharial, and actually following their movements. They're being watched everyday as we speak, to try to find out what this mysterious toxin is.

The Chambal river is an absolutely incredible place. It's a place that's famous to a lot of you who know about the bandits, the dacoits who used to work up there. And there still are quite a few around. But Poolan Devi was one [of them]. Which actually Shekhar Kapur made an incredible movie, "The Bandit Queen," which I urge you to see. You'll get to see the incredible [Chambal] landscape as well.

But, again, heavy fishing pressures. This is one of the last repositories of the Ganges river dolphin, various species of turtles, thousands of migratory birds, and fishing is causing problems like this. And now [these] new elements of human intolerance for river creatures like the gharial means that if they don't drown in the net, then they simply cut their beaks off. Animals like the Ganges river dolphin which is just down to a few left, and it is also critically endangered.

So, who is next? Us? Because we are all dependent on these water sources. So, we all know about the Narmada river, the tragedies of dams, the tragedies of huge projects which displace people and wreck river systems without providing livelihoods. And development just basically going berserk, for a double figure growth index, basically. So, we're not sure where this story is going to end, whether it's got a happy or sad ending. And climate change is certainly going to turn all of our theories and predictions on their heads. We're still working hard at it. We've got a lot of a good team of people working up there.

And the thing is, you know, the decision makers, the folks in power, they're up in their bungalows and so on in Delhi, in the city capitals. They are all supplied with plenty of water. It's cool. But out on the rivers there are still millions of people who are in really bad shape. And it's a bleak future for them. So, we have our Ganges and Yamuna cleanup project. We've spent hundreds of millions of dollars on it, and nothing to show for it. Incredible. So, people talk about political will. During the die-off of the gharial we did galvanize a lot of action. Government cut through all the red tape, we got foreign vets on it. It was great. So, we can do it. But if you stroll down to the Yamuna or to the Gomati in Lucknow, or to the Adyar river in Chennai, or the Mula-Mutha river in Pune, just see what we're capable of doing to a river. It's sad.

But I think the final note really is that we can do it. The corporates, the artists, the wildlife nuts, the good old everyday folks can actually bring these rivers back. And the final word is that there is a king cobra looking over our shoulders. And there is a gharial looking at us from the river. And these are powerful water totems. And they are going to disturb our dreams until we do the right thing. Namaste. (Applause)

Chris Anderson: Thanks, Rom. Thanks a lot. You know, most people are terrified of snakes. And there might be quite a few people here who would be very glad to see the last king cobra bite the dust. Do you have those conversations with people? How do you really get them to care?

Romulus Whitaker: I take the sort of humble approach, I guess you could say. I don't say that snakes are huggable exactly. It's not like the teddy bear. But I sort of -- there is an innocence in these animals. And when the average person looks at a cobra going "Ssssss!" like that, they say, "My god, look at that angry, dangerous creature." I look at it as a creature who is totally frightened of something so dangerous as a human being. And that is the truth. And that's what I try to get out. (Applause)

CA: Now, incredible footage you showed of the viper being killed. You were saying that that hasn't been filmed before.

RW: Yes, this is actually the first time anyone of us knew about it, for one thing. As I said, it's just like a little snack for him, you know? Usually they eat larger snakes like rat snakes, or even cobras. But this guy who we're following right now is in the deep jungle. Whereas other king cobras very often come into the human interface, you know, the plantations, to find big rat snakes and stuff. This guy specializes in pit vipers. And the guy who is working there with them, he's from Maharashtra, he said, "I think he's after the nusha." (Laughter) Now, the nusha means the high. Whenever he eats the pit viper he gets this little venom rush. (Laughter)

CA: Thanks Rom. Thank you. (Applause)